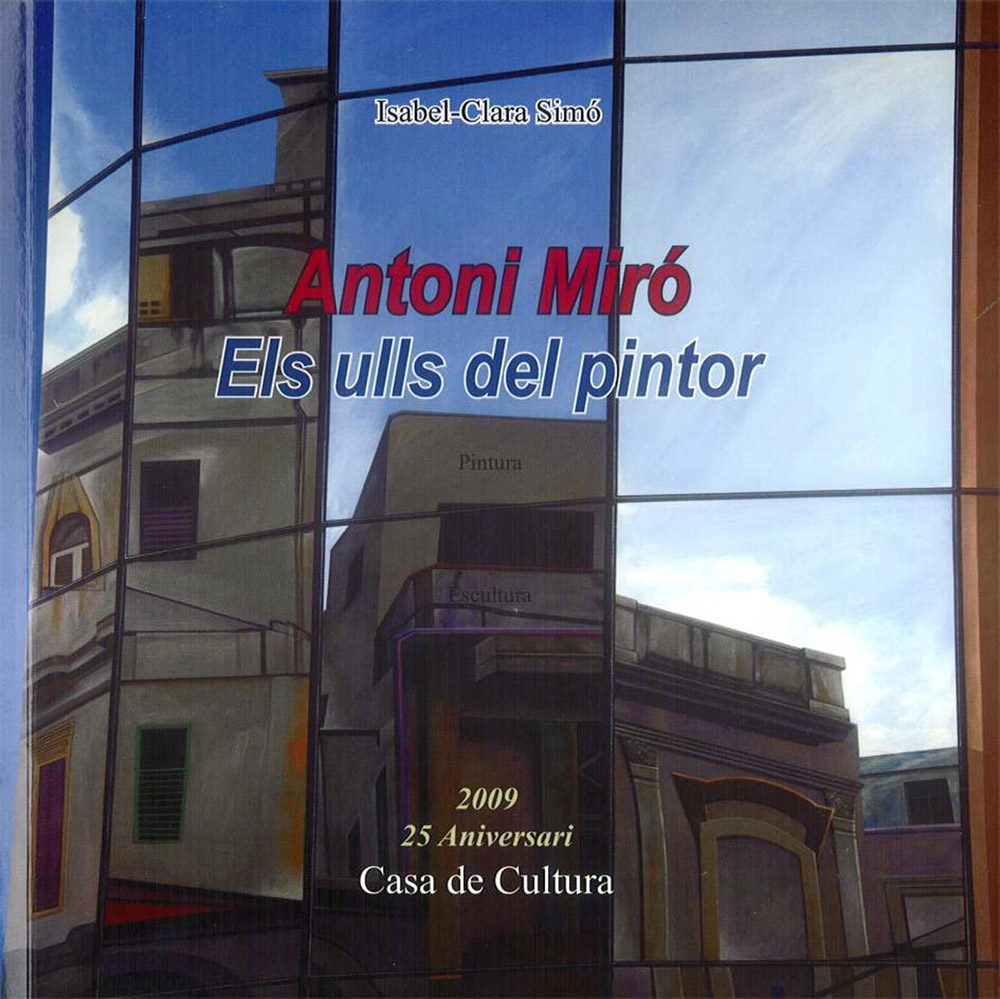

The eyes of the painter

Isabel Clara Simó

The painter looks at reality and transforms it. He transforms it in three different and simultaneous ways: he transforms it by giving it meaning; by rescuing it from the daily routine that dulls objects and people; and, by projecting his own alternative world, created by the artist, on it. With the first transformation the painter explains our surroundings to us by taking apart the rhetoric of power; that is, by opposing the vindictive justice of his own gaze to the established order. With the second transformation he wipes the mist from the glasses of programmed perception, according to which we only perceive what we expect to perceive. With the third one, the artist becomes a revolutionary because he catches the official world and makes it face the alternative world that he has created. In this sense, it is a libertarian act. To create is, thus, to infringe and show us how to look.

The artist’s task becomes essential when we walk through a city because it renews the city of the tourist (these captivated and non-critical beings are made fun of in Catalonia by mimicking their exclamations of “how pretty!”), the organized city of the police officer and the opulent city of the shop windows that drown the city of the people.

Antoni Miró’s case is, in this sense, transgressor and transforming and, for this reason, it is especially shocking. His eye, the artist’s eye, penetrates the skin of the city and sometimes looks at the obscene face of destitution, sometimes at the domesticated face of passers-by, sometimes at the severe face of official buildings or at the solemn tributes to prestigious citizens. Miró points his finger at a façade, or at young smiling women, or at the held-out hand of a beggar and reveals them to us, he extracts them from the background and pushes them to the front. And we don’t like what we see. It’s like putting a mirror in front of our confused face, or of our guilty face , or, in sum; of our rhinoceros face (do you remember Ionesco? He wrote an unforgettable play: The rhinoceros, where, in the style of Kafka’s metamorphoses, he introduces a citizen whose skin thickens at every step he takes until it is so thick that his whole body has turned into a rhinoceros).

Modern men and women have turned into city dwellers at the same time that they furiously miss nature, in permanent contradiction. Contemporary metropolis have a characteristic trait: they resemble each other more and more. The differences are found in the cities’ old quarters, but one airport and another airport, one hotel and another hotel, one museum and another museum, a lit promenade and another lit promenade, one theatre and another theatre... Some artists have even superimposed the tube maps of the most populated cities and have seen coinciding codes. The second characteristic trait is that cities swallow up individuality: the human being who walks in them becomes anonymous by decree and so interchangeable with any other. The third trait is hypocrisy: we hide poverty (not always successfully), prostitution and criminals and, when visitors arrive (tourists, disposed to spend their money to see what they never see at home, such as museums or churches), the authorities wash its face and dress the city in its Sunday best. And then Antoni Miró appears and looks at it with fresh eyes, scratches the city’s skin (in the same way that Dali lifted up the skin of the sea) and, while pretending to be objective, like any good portrait artist, throws a new light that hits our conscience without being able to avoid it.

In this new series, the one about the passers-by, Antoni Miró’s originality is at its highest. And, as usual, he pokes fun at what he sees and at us without forgetting his dense, unstoppable spring of tenderness. It is the most human of Antoni Miró’s series; and the most disquieting one.