Paint history

Josep Sou

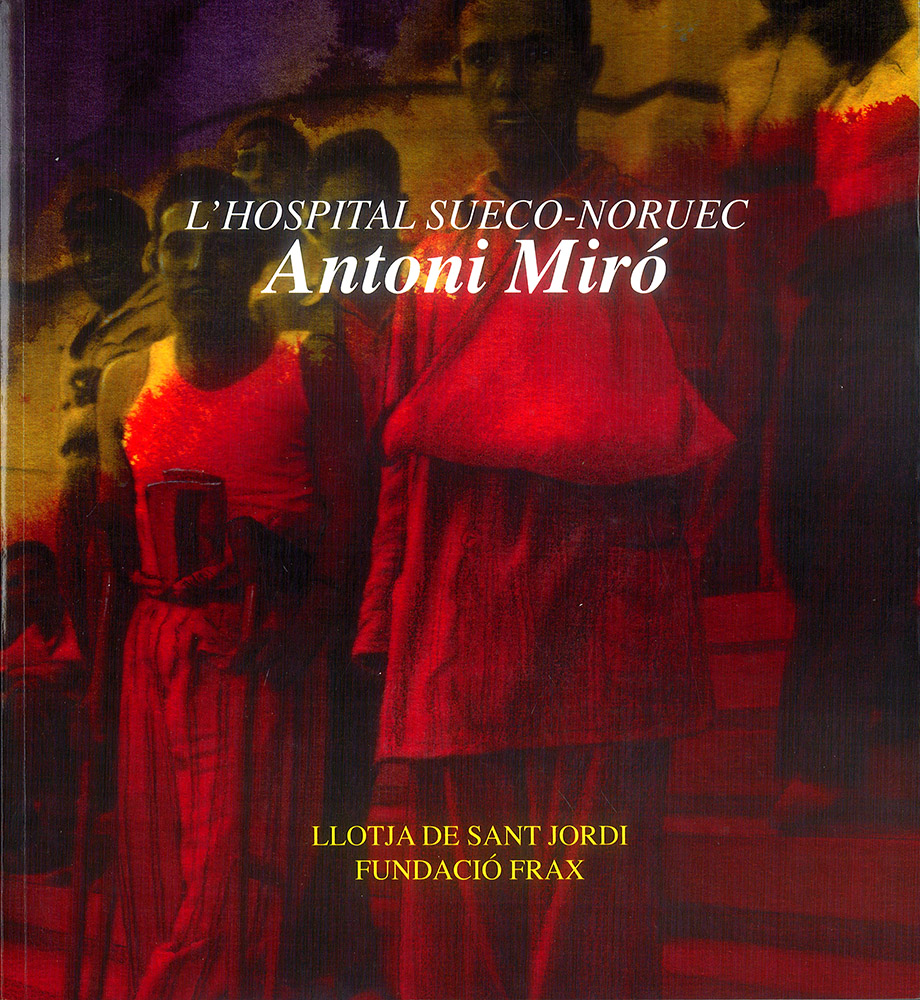

(Visual chronicle of the Swedish-Norwegian Hospital in Alcoi)

The painter Antoni Miró will never stop surprising us. And it happens also the same with his work, his careful and very generous work; because if capturing the unusual is an essential exercise in plastic, or artistic, culture, in Antoni Miró’s paintings surprise is guaranteed for sure, both by the depth of the treatment of organic matter he does and by establishing links with reality and time. Also with memory.

And the work building this wonderful visit to the halls of history talks about researching past time, and about reinterpretations of a recent caring time. Areas where drama, in its final sense of movement, flows, releasing the warm atmosphere of the men found there. Work often growing in intensity; so much intensity as surely there was on the days when the drawn chronicle happened: where interest is lost, memory is lost, Goethe says. And Antoni Miro, of course, agrees with him too.

And now, if we establish a link, even only for textual neighbourhood, between what history, or the way to approach to it through texts, and literature, mean, and we value everything next to the pictorial work, which stubbornly tries to translate to us, through images, the facts of history or the texts talking about them, we would prove the Horatian quote that says: ut pictura poesis (as well as painting is poetry). Throughout time, they have established close relationships between the behaviour stemming from the pictorial action and the approaches to the literary event. Horatian proposal refers to the pollution appearing between the different ways of approaching to what is creative, but it is no less certain the position of those who are not convinced of such proximity in the treatment of matters of art, such as G. E. Lessing who, in his Laokoon (1766), points out the specific nature of each of the creative disciplines to contribute to areas of knowledge. What remains clear, however, is that both literature, and history, or even intertextuality (such as Joan Brossa’s work, comics or the textual display of Art & Language), also painting as a portrait of certain moments of men’s existence, mean instruments for knowledge.

Well then, the work we are looking at/contemplating today, which translates us events from our immediate world, painting dressed with the nostalgic contrasts from the past, releases a tender poetic scent where silence is also listened: painting is a dumb poetry, Simonides whispers to us. And yet the painting in this exhibition, from the harmonious silence of the canvases, talks widely to us about the time it reinterprets, about the contours of travelling history, about the nuances, sometimes so thin, of the events stating, through distance, the root of the symbols of harmony. This painting, carried out from the paths of truth, and digging borders, or margins, in books on shelves of neglected dust, encourages us to scrutinize the recent past and to wonder ourselves caustically about the reason of so many miseries and so many lives without life nor hope. A moment, however, for meetings providing the rescue of our own certainty. So, with Seneca, we will say: the language of truth must be simple and without artifice. Also in this main lobby of time, Antoni Miró tells the truth when he paints, when he embraces the atmosphere of a past we care, when he turns the daily way of experiencing the landscape of stones into poetry and now these stones are like the pages of a calendar, recognized in the gestures. To a great extent, the painter, the poet, in a great approach to events, experiences before understanding. Passion and sensitivity.

Painting, as this exhibition reveals, uses the evocation of images to express itself. Form and content twins with a certain discipline effective to reveal the flow living in the heart of the summarized episodes. Painting has an internal, true and mimetic approach to reality, although the approach to the contents of reality may be somehow subtle and escaping. This proposal, this visual reality, researches, both in motion and in the added imagination, a quality that avoids statism. Movement that, not being typical of pictorial art, and being trapped as it is in the double dimension, breathes deeply and breaks the seal of the frame to ride, from memory, to the wonder of the accomplice commitment. And if man, men, cannot tear their own shadows and jump a little further, they will find, in the push of the picture, a foothold to make it happen. Or as Rilke suggests: turn your wall into your step. The issue is to undo the network, or undo the skein.

Maybe this painting we are looking at is also a tasting that ties our likes with the need to know more and more about everything we have been. A task needing so many hours of study as those spent to display the life in the Swedish-Norwegian Hospital in white on black.

Painting as a chronicle patiently built in vast nights of vigil. And later adding two creative sides that, melting different cultures grant quality and credibility. And as Hegel would say (and in the present case it also will link to the painting willing to be a chronicle of a neighbouring reality): history is the progress of the consciousness of freedom. And Antoni Miró has understood it perfectly.