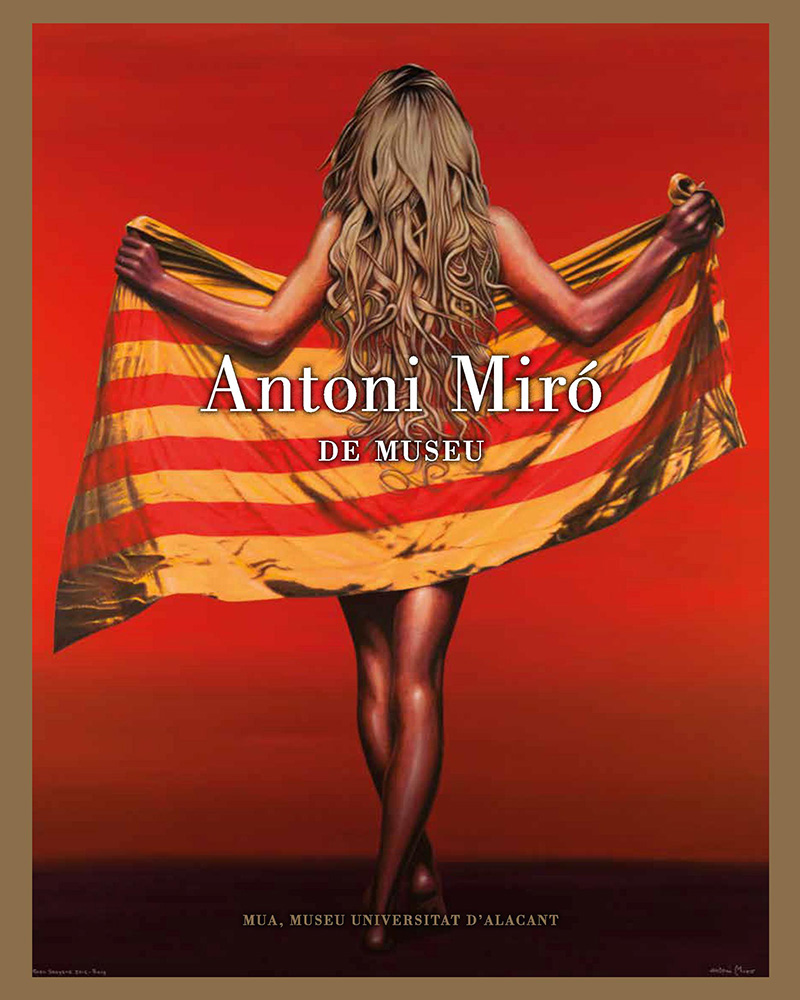

Nus i nues

Josep Sou

«...todo pasa; tan solo el arte pujante es eterno» Théophile Gautier

La desnudez del cuerpo; el arte revisitado donde la belleza abraza, sin estrategias deformadoras de la propia voluntad, la magia de un franco ofrecimiento. Allá donde la piel ciñe la cuerda del misterio reside el ejercicio del deseo, a veces conformado en placer sin reservas ni prejuicios ancestrales. Y se muestra la fuerza de la cultura sobre la espuma de un intenso mar de tradiciones y de leyendas: ninfas, hadas, y sirenas, que deshacen los nudos de una cuerda invisible para viajar desde la otra ribera del conocimiento. Grecia, tan cantada, se retuerce en ciento y mil complicidades para embellecer el rostro inefable de la vida: el cuerpo es vida cuando todos los fluídos calan, sin nostalgia, el apocalipsis del placer. Roma, tan culta e intensa, desde el poder del hierro en la espada del dominio, vierte el cántaro del amor cosechado, todavía recientemente, en el tálamo encendido de las caricias en abierta reciprocidad. Y los barcos, en su travesía, nos sugieren la vocación por satisfacer el camino de ida, cruzando los muros de la necesidad. Y la espuma, cuando se eleva desde el océano y nos salpica el rostro, enardece de aroma y de sal la esperanza gratificante de la aventura.

El pintor Antoni Miró, en la profundidad de sus espejos inalterables y en la lucidez íntima de su discurso creativo, nos convoca hoy, como siempre lo ha hecho, para gozar del contacto delicado de la experiencia. Y los cuerpos, ahora desnudos, cándidos en la reverberación de la noche insomne, ofrecen todas las potencias que el interés identifica. Una especie de caos nocturnal donde la alegría y el llanto conviven a tientas, entre las ramas colmadas de inquietud y de un frágil rocío. Es el amor; es, todavía más, la vida. Es la identidad versátil de los cuerpos firmes para redimirse en instantes fecundos de placer remoto. Pero ahora, también, ofreciendo la brasa intensa de su quehacer hermoso. Es el amor, tacto armónico, revestido de especial circunstancia, y que alienta hacia un futuro lleno de incertidumbre, pero con la necesidad de estimar, y de ser estimado. O tal vez sea el contacto frágil de la belleza que ampara el norte y guía de la observación limpia y luminosa: “...no es la belleza lo que inspira la más profunda pasión. La belleza sin gracia es el anzuelo sin señuelo. La belleza sin expresión cansa”, razona intencionadamente Ralph W. Emerson, cuando establece los límites que la belleza ampara a la hora de ponderar las categorías que ciertamente inspiran la especial cualidad de lo bello, y por tanto proclive a la íntima verdad de un principio austero.

¿Nos pertenece la belleza? ¿Residen en nosotros las herramientas suficientes para reconocer las bondades que de ésta se derivan? Seguramente los razonamientos podrían verse enfrentados, dependiendo de las valoraciones que unos, o bien otros, lleven a cabo. La belleza tal vez sea el eje fundamental que dirige la mano del artista Antoni Miró para escarbar en el barro que acoge la materia primera. La pintura, ahora, se vierte hacia las regiones de la escultura, elevando los mármoles inquietos que adormecen el regalo del cuerpo ferviente, natural, cálido y, al fin, sorprendente. Un requiebro de posturas substancian el coro que canta en voces arribadas desde el infinito de la tradición helénica. Desbastar la tierra, quemar la arcilla y acariciar el rostro, todo a la vez, por un puro deseo aventurero. La pintura de Antoni Miró, ahora, una aventura.

¿Y si el sueño fuese, también ahora, una aventura? El sueño y el trance que procura. La magia de los colores que rebrincan en el mortero del alquimista, con los marrones inesperados para la feliz interpretación de la carne que se ofrece formidable, vaporosa y tejida de caricias. Unos cuerpos que se insinúan por la rendija de una visión feliz, risueños e impregnados de voluptuosa necesidad. Ninguna ojeada se altera en aras de la melancolía aviesa. Ahora son intenciones precisas, instintivas, auspiciadas por la voluntad de alcanzar la libertad, y con enorme fidelidad hacia la existencia apreciable de los días sin trampas impertinentes, tan miserables.. Cuerpos para el canto de la libertad, y los pinceles que orillan la riqueza de los matices corporales, a modo de estipendio bien adquirido cuando ilustran la virginal fantasía del placer remoto, por profundo y estimado: “...nada os pertenece en propiedad más que vuestros sueños”, percute el tambor de Nietzsche cuando, ahíto de razón, instala la eficacia del pensamiento íntimo en la maravilla inaprensible de un sueño azaroso y discontinuo. La lógica del pensamiento, y de la virtud que lo acompaña. O tal vez un misterio, finalmente, lleno de elocuencia.

Y los cuerpos, ellas y ellos, para frecuentar el sabor de la vida. Son, puede ser, una enorme paradoja, o bien se resume imprescindible la materia orgánica en función primordial, próxima al sentimiento. Todos los nervios a flor de piel, todo el paradigma biológico para herir la intimidad caprichosa, casi ignorante, de su potencialidad. Y el placer ya es una sonrisa potente, un contingente de telas para abastecer la pasión elemental que empuja la vida. Sería mezquino no reconocerlo. O tal vez sería una lástima no tomar parte en la conquista de la alegría. También, ahora, suprema garantía de libertad. ¿Y por qué? ¿Y para qué? Pues porque desde la discreción del ánimo nos sobreviene la necesidad de perpetuación. Y la pintura, ahora ya casi escultura, y desde la luminosa ventana del arte en estrecha complicidad con el futuro, pueden ser una buena oportunidad para garantizar la vigencia de los días. Un fracaso sería abandonar la visita que nos ofrece la creatividad del artista en el momento de construir, por qué no, la epopeya de la vida; la capital incorporación, sin reservas, de la comprensión de los hombres: “...todo lo que vive, resiste”, acudirá en nuestro favor Georges Clemenceau. Así el arte. Así la pintura que ahora nos convoca: los Nus i Nues de Antoni Miró. Crece la mirada, pero también, la ilusión por la existencia. O como incluso se pronuncia Malcom Forbes: “...mientras vivas, vive” añadiendo un nuevo concepto que se acomoda a la necesidad de aprovechar el momento que la vida nos otorga: “collige, virgo, rosas” que acuñaría, con tanta precisión Ausonio.

Amor, vida, pasión y deseo, con el aura fundamental del arte que todo lo articula y arropa; fundiéndolo con proporciones subordinadas al imperativo de la creatividad del artista. Antoni Miró esculpe los cuerpos, los ilustra con la pátina inteligente de la mirada; los dota de vida en un instante preciso de gracia, y ya todo irrumpe en el claustro materno de la contemplación. La armonía será también el talento que inspira el contacto con la realidad de la carne que baila para hacerse presente. No aparece tan solo la fecundidad de la inmensidad que se suscribe en la calidez de la fibra cordial. También el flujo sensual se desinhibe facilitando la intemperie de las emociones. Y también eso mismo vive en los cuadros de Antoni Miró. La voluntad de emancipar hilazas de sensual existir, así como la mirada esquiva deposita el encantamiento en la cúspide de las horas densas de la noche. La participación de los víveres gratificantes del ímpetu sensual, la pulsación de los frutos sabrosos de la nocturnidad fustigada por el deseo: “Aunque cierra la boca, si es eso lo que quieres,/pero dame parte al menos en tu amor”1 interviene Catulo en nuestra reflexión, comprendiendo el alcance infinito de voluptuosidad amatoria.

Los cuerpos, el sexo, la erótica sensualidad enardecida, como los guerreros ateneos a las puertas de la gran batalla, y donde el sol fundirá las espadas y las corazas. Una Ilíada herida y de pies alados sobrevuela la metáfora para incorporar la gracia del discurso pictórico. Y en la oscuridad tintinean, de perfil, los hombres, percutiendo los miembros altivos en libre competencia con los órdenes arquitectónicos. Y la pintura canta, como lo han hecho los poetas, y también las palabras de los rapsodas en la plaza pública. Espacios para la alteridad, para las razones y para la fantasía, también. Los deseos son, ahora, libres. Y los saltos de unos pechos desmesurados retan la medida cabal cuando se incardinan en el entusiasmo del juego abierto para el gozo.

Miembros que son héroes llegados desde la poesía. Substancia de nuestro tiempo, y pretérito al mismo tiempo. La pintura canta, como lo hace la música en el recuerdo del murmullo del universo. El arte, en la pintura de Antoni Miró, se nos presenta llamativo, homónimo de un entusiasmo siempre vivo desde la arcadia de los colores. Todo contribuye, porque todo se aviene para curar las heridas de la inquietud inconsistente. La pintura es como un eco ancestral que vive para remediar la insatisfacción del olvido. Antoni Miró gana tiempo al tiempo como si fuese lo último que ha de vivir: cada cuadro un mundo, y con todos los mundos que tiene en sus manos forja un auténtico universo substancial: formas, ideas esenciales, substratos de la experiencia, vigor comunicativo, elemental voluntad de abrazar los misterios de la vida, todo, en armonía permanece en los espacios de su imaginación prodigiosa. Antoni Miró teje, desde la memoria, puentes que posibilitan los encuentros en los llanos de la cultura: “...Cuantas veces bajo el sol tuve sed/de veros, héroes y poetas de otro tiempo!”2, apostilla Hölderlin, cuando canta la necesidad de la memoria para construir los edificios de la sabiduría y del conocimiento.

Y la pintura de Antoni Miró, ahora, se precipita como lo hace la lluvia generosa sobre los campos henchidos tras el paso del arado. Los cuerpos dibujados rebotan la geografía de los cuadros para saborear la verdadera turgencia de la realidad cósmica de los afectos, del amor y de la pasión que comportan. Cuerpos nobles a orillas del deseo y de la profunda intimidad. Cuerpos que reviven el interior de su esencia para embellecer la necesaria contemplación que los resuelva grandes, enormes, inquietos y totales. Cuerpos desnudos como una celebración, como una victoria de los sentidos, como una voluntad de existir en la comedia de cada día. Cuerpos alterados por la gracia cuando la misma se disocia de la realidad parca en metáforas, pues la filigrana representativa maniobra para otorgar los ritmos gozosos de un verdadero instante de placer. Y de lo común, de lo cotidiano, ahora, surgen, sin pereza, el atrevimiento, la oferta dinámica de la ironía y, tal vez, también, del humor. Porque, de estos momentos de reencuentro con la carnalidad indisimulada, la llave permanece suspendida en los clavos del amor posible, de la franca mirada, y tan libre: “Cuerpo – de color y calor,/de fuego, de luz y de vapor./Cuerpo – destinado a ser ceniza/y a la inconsciencia solitaria de sí./Tú que para darte cuenta no puedes no quemarte./Tú que no puedes agarrarte al instante que te ama”3, capturamos, en este momento, los versos de Giovani Judici, para abordar la intensidad que significa el hecho amoroso, el absoluto abandono en brazos del idilio que determina la pasión amorosa, tanto como el escalofrío que supone; así pues, de igual modo lo recibimos en la pintura de Nus i Nues del artista Antoni Miró.

No obstante todo lo que ya hemos comentado en este texto de acompañamiento: la fuerza de la expresividad emotiva en la profunda substancia de los cuadros, también nos complace significar otras aportaciones, la singularidad de la cuales se manifiesta en la dulzura, la suavidad y la libre interpretación del canon clásico. Tal vez el matiz sorprendente, también conductual de los protagonistas últimos, abrazando los paradigmas de la modernidad, ilumina la escena general con la ternura de la confortación. Sí, la contemplación nos deposita en las manos la pertinente carga cultural que nos llega desde la otra orilla mediterránea, surcando travesías de conocimiento, y cobijados, éstos, en el infinito de la historia que nos pertenece e interpela. Tal vez una saga de vehementes pasiones remotas para decir, con solvente sencillez, acerca del amor: “...Qué noche más bella amor!/Con perfume de luna tierna,/navegaremos por el perfume/que tendrá regusto a menta”4, interpreta Rosa Leveroni este caudal de ternura que el amor, y su ausencia, determinan.

Los Nus i Nues de Antoni Miró, una nueva posibilidad que nos brinda el artista para jugar, a través de las manos de la memoria y del rigor del presente, con el barro del misterio cordial: el deseo como motor de la existencia.

1. Catulo, Poesía Completa (C. Valerii Catuli Carmina) Versión castella de Juan Manuel Rodríguez Tobal. Ed. Bilingüe. Poesía Hiperión, 3ª Edición, Madrid 1988. p. 119. La versión latina dice: «...uel, si uis, licet obseres palatum,/dum uestri sim particeps amoris»

2. Hölderlin, Obra Poética Completa. Edición Bilingüe (Tomo I), Libros Rio Nuevo. Barcelona 1986, p. 117. El texto original dice: «...«...Wie oft im Lichte dürstet’ ich euch zu sehn,/Ihr Helden und ith Dichter aus alter Zeit!»

3. Giudici, Giovani, en El Fuego y las brasas (Poesía italiana contemporánea), Antologia a cargo de Emilio Coco. Celeste, Sial Ediciones, Madrid 2000, p. 53. El texto original dice: «Corpo – di odore e calore,/di fuoco, di luce e di vapore./Corpo – votato alla cenere/e all’incoscienza solitaria di sé./Tu che per darti non puoi non bruciarti,/Tu che non puoi aggrapparti all’attimo che ti ama.»

4. Leveroni, Rosa, en su poema Absència, en Nou Segles de Poesía als Països catalans, a cargo de Celedoni Fonoll, Edicions del Mall, Barcelona 1986, p. 325. Nuestra ha sido la traducción al castellano.