In Praise of Experience

Josep Sou

“Only one’s own personal experience makes one wise”.

Sigmund Freud

At this stage of the life of the artist Antoni Miró, a great deal will need to be said to evaluate his painstakingly intense creative work. And we will have to accept the great difficulty of the challenge, because he is a painter who has made of his work a highly noble and ethical raison d’être. And fuelled by his constant creative drive, one can say that his extensive, steady and formally enormously complex work contains an edifice of committed analysis which has made it possible for him to construct, within the bounds of an honest and truthful respect for his subjects, something truly intimate.

Every day, perhaps when the light is already fading on the blue mountain horizon, his work begins. His colours are the raw material with which he puts his stamp on realities, ideas and thoughts; his brushstrokes drive away the lethargy of the day and, frenetically, begin to daub the vast territory of his canvas; life, once again, reaches its zenith, asserting the hidden power of a sensitivity which knows no limits: in the words of Charles Baudelaire, “inspiration is working every day”.

And it isn’t just anything which inhabits the complex essence of each of the painter’s reflective canvases. No, there is a whole range of universes which emerge from within the painter’s inner world to alight in the hearts of the many in the outside world, because the painter’s artistic work is very far from being a cosy chat amongst friends; he responds to the need we all have to grow and to love. These are the non-negotiable conditions of an expressive and militant attitude. Antoni Miró accepts Elbert Hubbard’s maxim that “Art is not a thing, but a way” and harnesses all his intelligence to this end, avoiding any kind of banality, and creating a poetic corpus, or pictorial corpus, or perhaps they are one and the same, in search of a necessary complicity with his audience.

Thus, rather than a meaningful mannerism, the ultimate intention of the artist is to guide his focus from his creative passion in search of the passion he needs to paint. And he doesn’t just show us his vision of the world around him; on the contrary, he grants us a privileged insight into the way he thinks, because the way he thinks is the way he paints. Or rewrites, with paint on a two-dimensional canvas, the intimate cosmic vision of the essence of the philosophy granted him by the full extent of his humanity. Thought rules supreme, perhaps. Or the enjoyment of showing every single one of its strands. And this is not just praiseworthy; it is also a powerful virtue, as truth, genuine truth, anticipating the paths of experience, rules in favour of light, of the unambiguous words which ennoble each stroke, each of the details which inhabit the communicative space of his immense oeuvre. He expresses the world as he sees it.

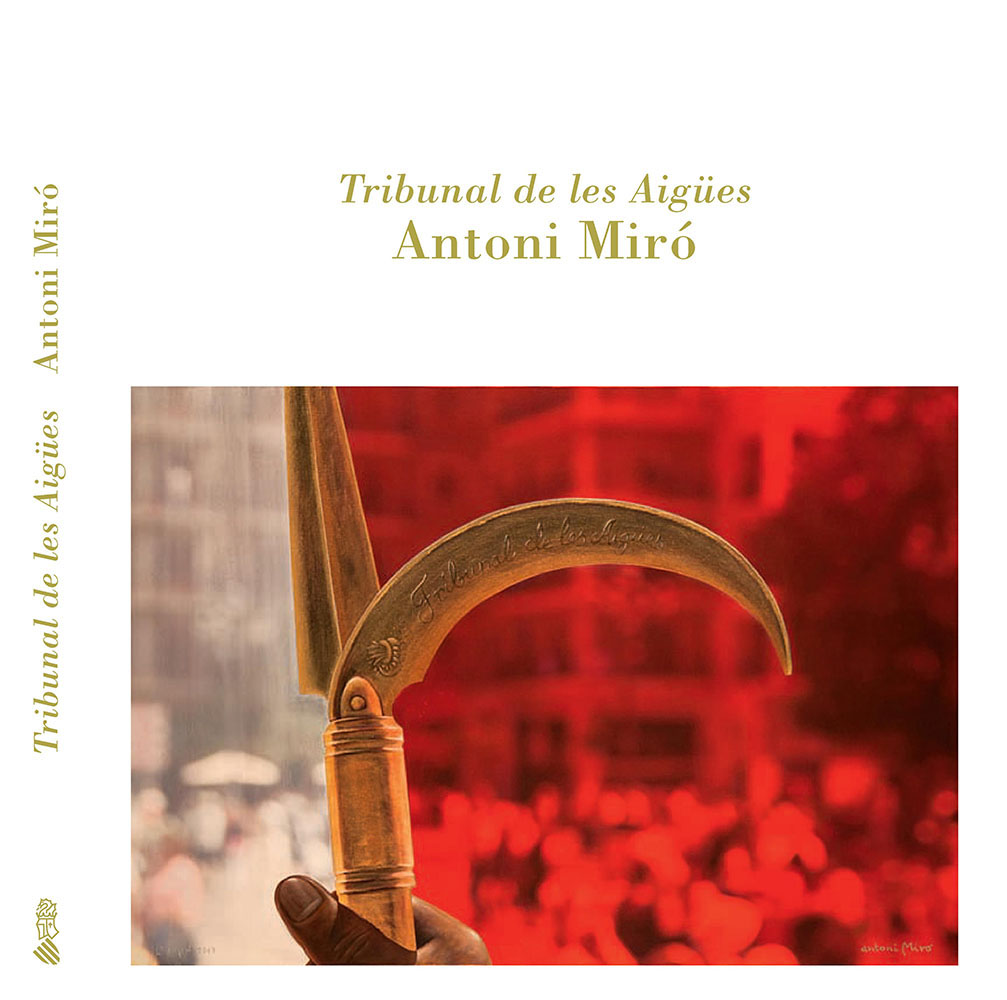

And experience, far from blunting his creative drive, enables him to express or rehabilitate realities which are truly ours, such as the Water Tribunal. And from his courageous canvases boom out scenes delivered by voices who resolve the cases and realities which are unique to our land. And as in a Greek tragedy, time stands still in order to record the accords of gods who provide sophisticated solutions to the earthly conflicts of men. Antoni Miró makes of the Tribunal his own cause and links his analysis to the time erected by memory. Whether remaining silent or speaking, the wise men piously deliver their verdict. The painter sees this and applies his art to exalting the courage of a time which grows rhythmically, new in history, alienated but with a sense of belonging to the canons of tradition. And these are paths which cross. The wise men’s experience matches the desire of the artist to kindle the embers of this complex tradition. Nevertheless it is all carefully nurtured, with the vocation of serving the common good. In the same way as the need to deliver justice to anyone who requests it also belongs to the creative endeavour of art. A consensus of wishes or a unanimous agreement, but made in advance. And the artist, without losing heart, resolves this position very satisfactorily thanks to an unquestionable desire to express his modernity, that which lies at the very heart of the Water Tribunal. The painting doesn’t incorporate any stronghold of his vision, but his interest in a jewel which comes from the past and is projected into the future. And Antoni Miró, who demands so much from himself, demonstrates his judgement in the face of the taunts of modernity. And this is, perhaps, a genuine paradigm also: “The beauty of things exists in the spirit of the person who beholds them”, said David Hume wisely. And Antoni Miró makes of Valencian beauty an act of creation, and with his brushes casts a favourable glance at history, or perhaps at the future.

The delight which comes from the elemental proceedings of justice can be perceived through the slits in the stained glass of the age-old kaleidoscope of time. The merits of having being perpetuated throughout time encourages certain regal but relaxed attitudes. The artist knows this, recognises this and transmits it in all its glory to the people who come to see and to listen. And as mentioned before, it is the work of tragedy to whisper in the wind into the ears of the men whose melodious voices determine the destiny of men. And now a tribunal, The Tribunal, delivers the benefits of a freely granted justice, a daring, even solemn justice. The artist Antoni Miró lives up to the challenge of filling his pallet with colours which speak of an age-old ceremony which is still alive today: “Everything must be taken seriously, but nothing tragically”, said Adolphe Thiers.

Experience as well as prudence warns the painter to be acutely conscious of the need to express the longevity of a tradition which goes back a thousand years or even longer. And the depth of the artist’s vision manages to represent this immense scale of time. This activity which seems to come from the very beginnings of time to make its home in our social customs gets a new creative boost, new breath, and capitalises on the historical moment it presides over. And art encapsulates accurately and vigorously an intellectual respect for the history which is always around us. An enormous joy for a noble cause which grants access to an active reserve of the nutrients which feed hope and thoughtfulness.

Nevertheless, it is necessary to expand on a special and highly personal characteristic of Antoni Miró, which is the constancy in his work. We could even say his stubbornness in the face of his creative responsibility. His congenital sense of vocation. And we could also speak of the way he communicates his work to all the citizens who come to see it. And the benefits are fairly distributed, in equal parts, and no crumb is lost from the sack of the shared flour: his work is very difficult, far from Manichean positions, and devoted to a collective genesis, as we have asserted earlier: “Individual efforts lead us to general progress”, says Cesare Cantù. We could say, for example, that the individual interpretation of Antoni Miró’s Water Tribunal is an intimate commitment which comes from contemplation and internalisation of the common feeling of all the people who lend him their support. And as Goethe said: “Without hurry, but also without rest”. Constancy, patience, daily struggle, all combine to achieve the sufficient degree of experience to allow the artist to take on a work which is as unique as it is committed. And it is not easy nor an experience accompanied by sophistication to understand how challenging it is to paint memory or paint the magic imprint of an oft-repeated past. Rather it involves exercising the will to go to the very ends of imagination and to cross over to the other side: in the words of the great poet Ovid, “Gutta cavat lapidem, non vi, sed saepe cadendo”. And for what is this effort and this constancy in favour of his own experience? We can assert, without the least possible doubt, that the basis of culture is always at the very bottom of Antoni Miró’s intentions. Yes, culture as a tool to reconcile us to the capital sin of feeling human, yet humans who are alive and involved in the society to which we belong. Culture as a vehicle to achieve the full range of what we are as humans. Culture as an elixir to coax us from the shadows. Culture, finally, like a primitive lair to make it possible, and perhaps profitable, to taste freedom. Even, as Emile Henriot asserts, “Culture is that which remains in a man when he has forgotten all else”. Or at least, Antoni Miró makes a gift of the cultural fact of his creative work.

Thus, work of this nature can never be confused with the vagaries of fashion which destroy everything in their path. It is a task that this noble as it is profound; as serene as strident against the lethargy provoked by conformity, which always ends up being entirely unjust. And sometimes, everything which leads to reflection, all that can be scented in the very interior of the vast brotherhood of thought in one’s beating bosom, combines to express what can be seen, because beforehand one has looked into the face or scanned the broad laws of history. And what originates in sentiments goes far beyond even what is being expressed. It is a question of opportunity or simply of desire. Things always end up fading away. This is perhaps the law of life, the stars and the storms. The more the fleshy fruits of ideas soak in the registers of thought, the greater their projection, the more they live on to temper generations and generations of men who profit from them, or, as Baudelaire reminds us, “what is created by the spirit is more alive than matter”. And it seems easy to recognise this, but it is not so easy to confirm it, believe it and put it to work. And Antoni Miró puts this maxim into practice and grants us, as we have said, consolation. And we are fortunate to enjoy it. And we benefit, here and now, from the truth described by Kalidasa: “The great souls are like clouds: they collect in order to give back”.

To return now to the main object of this essay – the experience which makes its way within the inner world of the artist –, it is necessary to assert that experience, amongst Antoni Miró’s other virtues, is a constant support to his creative endeavour. Why? Because his skill in creating forms not only provides a measure of the nature of his artistic discourse, but also, and uniquely, it helps him to confront all kinds of profound challenges. Like, for example, the one which concerns us here, the fixing in time of a project based on one main idea: the artistic representation of a phenomenon which is consubstantial with the land and with history. And this, in addition to posing a great risk, is also bold and worthy of recognition. And the result is what we can see here: a jewel in the temple of traditions which are the unique incarnations of a people. A type of industrious fragility to chase away the demons of a stale immobility. So, benefiting from the thought of the historian Thucydides, we can assert that “there is no difference between man and man. Superiority consists in learning from experience”. And so, day after day, time increases his vision as it, resolutely, roams around the well-known places of Valencia. A huge volume of work with time always pressing. “The experiences which teach you most are those of the day to day”, asserts F. Nietzsche. Always measuring the hours which establish a canon of ancient references, projecting shadows towards what is to come and which will mean the triumph of ideas. Always ideas. And experience is part of the wisdom of men, because it rises above the limits of uncontrolled desire. And, because, as Phaedrus asserts, “a man with experience knows more than a divine”. Intuition, intuition alone, is not sufficient to create a work as unique as that of Antoni Miró. It can help to feel one’s way forward, but one gains a more effective understanding if one constructs one’s own language with a profound dose of perseverance in order to investigate new elements to stimulate one’s own communicative language.

So, study, reflection, the poetics of balance and form to establish the syntax of one’s own work are not only essential, they are also resources to enable the construction of a standard for communication. And maybe it is precision, strength and stamina which gain as a result. However, there is no neutrality in Antoni Miró’s work. The cause comes first, then he takes contact, then lastly, he transforms ideas into concrete paintings in order to free the pleasure which comes from the contemplation of beauty. Although what we see in front of us may be extremely uncomfortable through its eloquence, its penetration, its objectivity and its rigour. And, at the same time all expressed with great simplicity: “Everything truly great is simple”, as Balzac asserted. Thus the painting we are privileged to see before us is testimony to the painter’s will to root himself in what is simple and captivating: a world in which justice is delivered and there is a collective imperative to accept the final verdict. The Water Tribunal guides us so we might avoid undesirable confrontation. Antoni Miró captures in this vision a world which is still alive thanks to those who meet at the Tribunal. An undoubted benefit for the cultural and social embers of a people who intend to still be a people long into the future. One must imbibe the past in order to guarantee responses enabling a future. Somewhat similar to art. And, as Emil Ludwig said, because “everything really great belongs to the whole of humanity”. And the Water Tribunal is great, without a doubt, as is the work of Antoni Miró, which reveals its commitment to men, but also to the time in which we are living. Thus, we can assert without doubt that both are great and belong to the happy band of those who are free. A commitment following a clear reality.

However, we could perhaps consider history, the history of each and every one of us, to be a description of the life we construct together. And history perpetuates us throughout time as a path that we have decided to walk together. So, one can glimpse a dark path which is struggling to conquer spaces of light and of dignity. “History is the progress of an awareness of liberty”, said Hegel. And in the creativity which is evident in all of Antoni Miró’s work is found this awareness and also that vehement desire, sometime in muffled cries, to conquer universes and erect scaffolds of knowledge. Day after day, as we have mentioned before. And to knowledge is added imagination; the creative taste and the greatness of eloquent forms which will be permanent witnesses of the history of us all. Events will pass, but the essential will remain for ever. The cause, however, can always be detected, as for Antoni Miró, nothing that is human is indifferent to him. Thus it is not necessary to make any contentions of this nature.

There can be no freedom, however, and we will never achieve that privileged state in the growth of men if there is no justice; imperious justice understood as an intrinsic necessity, as, “all the virtues are contained within justice”, as Theognis said. And Antoni Miró represents this axiom or rather this tautology, in his painting. His painting speaks of the reality of man in the bosom of his primordial universe and he recreates the sentiments of his restless and combatant spirit. His colours take the convincing form of the agreement for hope, as the prevalence of good is constant and consubstantial with the collective struggle.

And in his magnificent painting of justice, a justice exercised with full freedom and popular guarantees, we find the mosaic dedicated to the Water Tribunal. A solid, educational exercise which finds its solution in the winds of history. Past history but also contemporary history. The intrahistory of our people which has agreed on a cherished and familiar justice, a justice which has imbibed from the many sources of universal knowledge. From the whole down to the concrete, intimate and homely. We can also add that with memory we understand a large amount of what we are and we understand the lessons of the day to day as proven by the passage of time. As we can never be cast out by memory, given that there is no question that it belongs to us and lives uniquely and is rooted in the marrow of our dreams. And Antoni Miró certainly knows a whole lot about memory. Above all, he knows about the memory which takes advantage of the individual, the human being, to launch itself into the future. If this were not so, it would remain as a leaden weight which refuses to engage in any kind of enthusiastic or laborious activity. The projection of the shadows and the opportunity to live in hope is rooted in large measure in the spirit when it speaks of courage and daring in the face of the storm or the cynical capture of our battle positions. And all this, and much more besides, is constantly present in the work of Antoni Miró, who demonstrates the undisguised strength of determination. And this is good news for all of those who come to observe his work. All of it is formalised with the patience which demonstrates his knowledge. And with the admiring tenderness of his methodical endeavour which is safeguarded by the hand of intelligence. And because Antoni Miró, though inquisitive and patient at the same time, is not easily daunted. The existential reasonings which make up the artwork of the painter are, or have, the motive force of a convey fuelled by the flames of liberty: to think, speak and say what he considers apt at every moment. Afterwards, there is a mystic corpus which lives in the essence and the gestures of his main characters: let’s call it civility. And as Plutarch understood well and whispered in our ear, “patience has more power than force”. Easy to understand but not so easy to put into practice. Unless, of course, reason accompanies force, and in this special case sends one to take a position in the face of human conflicts. Alert to all issues of principle, essence or just cause, the painter, when silent, says much more than all those who speak at great length or give rein to the full flow of their stupidity. Aphorisms, inscribed in the holy books which nobody has ready attentively or made any attempt to understand, need to be taken into account as very often they illustrate the breeding ground of thought. We must not waste our time with daily work, as it is here and now that the cordial nuances of daily life are found. But it is also necessary to lift the veil in order to gain enough perspective to understand the whole, as, in the final analysis, we are all part of that beautiful artifice that is life, and because, as Democritus put it, “the homeland of an elevated spirit is the universe”. And Antoni Miró, with his painting, puts this into practice every day.

I have mentioned that we are brought closer to wisdom by understanding the possible universes in which the raw material of the spirit is inscribed. However, one must marvel, be in awe of things, the world and existence in order to sharpen our experience of happiness. If it is true that happiness can be proven to be possible. But we know that Antoni Miró constantly marvels and takes up causes which invite his burning enthusiasm. He paints to the dictates of passion and enjoys the results when they are understood by others. And to paint, as he has always done and does now, giving voice and wisdom to the Water Tribunal, is not only unique, but also a resolute attitude of astonishment before a miracle, before the conquest of a remote time of ancestral customs, with the desire to use the beauty of his creation to deposit a crumb of survival in the wrapping of an unattainable future. And it is a gift, a wise decision, and we feel gratified by the consequences of the painter’s effort, and we affirm the position of the artist as he takes sides with people, as he understands that this gives value to our communal life. The life of all of us.

Yes, work. If there is any one thing which defines most precisely Antoni Miró’s talent as an artist, that thing is work. Hard and persistent work in the long, waking nights. We have already mentioned it elsewhere, but it is what it is and cannot be hidden. Nothing is free. The mallet suffers when it is wielded in the middle of the night. And this great work yields fruit incessantly, good and tasty fruit (as the poet would say). Fruit in the multiplicity of forms which inhabit his substantial body of work. Colours which reinforce the passion of living at the source of sensitivity. That of living and painting the life led. His own and the lives of many anonymous human beings peer out through the window of the artist’s paintings, even though they may have led very paltry lives. All, all converges, is sung in the epic of the discreet man, the burning man or the reality which beats intensely under the clothes of an uncertain destiny. Everything. Everything lives in it. It oozes out, protected by the colours of the imagination. Sometimes it is hard, and sometimes, perhaps, sinister. And Horace’s words are apt here, “The pleasure which accompanies work makes us forget our fatigue”. This is very true, but at times it weighs on us. Yes, it weighs us down. But it lengthens our life. A life we would live as brave. Without weakness which prevents us from looking within the mysteries of existence with the keys of our knowledge. Firmness can also be a guarantee and a crutch for walking when it is difficult to continue. Fighting against the crowd, as Antoni Miró has always done, with the wind in his face, sometimes a freezing wind, sometimes from the west; but he always faces up to it and never gives up. And his painting illustrates this stubborn position. For a long time, always… “Heroes are people who maintain their ideas in the face of the commonplaces of others”, concludes Alexis Carrel.

But art, when it rises firm, when it embraces truth and reason, gains a place in the future and leads on to freedom. In the work of Antoni Miró, freedom gains greatly because it nestles close to the word truth. It is not enslaved by false appearances. There is a guarantee of authenticity, although it demonstrates loudly and clearly what is meant by the conquest of dignity. And all with broad strokes, without excess. All with the enthusiasm which produces alliances: When truth deigns to come, his sister liberty is not far off”, comments Mark Akenside in passing; but a true and resolute truth, very capable of attacking and winning over areas where one can live in harmony and peace. To gain authenticity and virtue which always accompanies the brilliant reality of humanity. That’s quite a jewel! What an extraordinary gift that Antoni Miró gives us every day that passes! And as Antonio Machado adds: “Virtue is strength”.