La dansa de Matisse (Matisse’s dance)

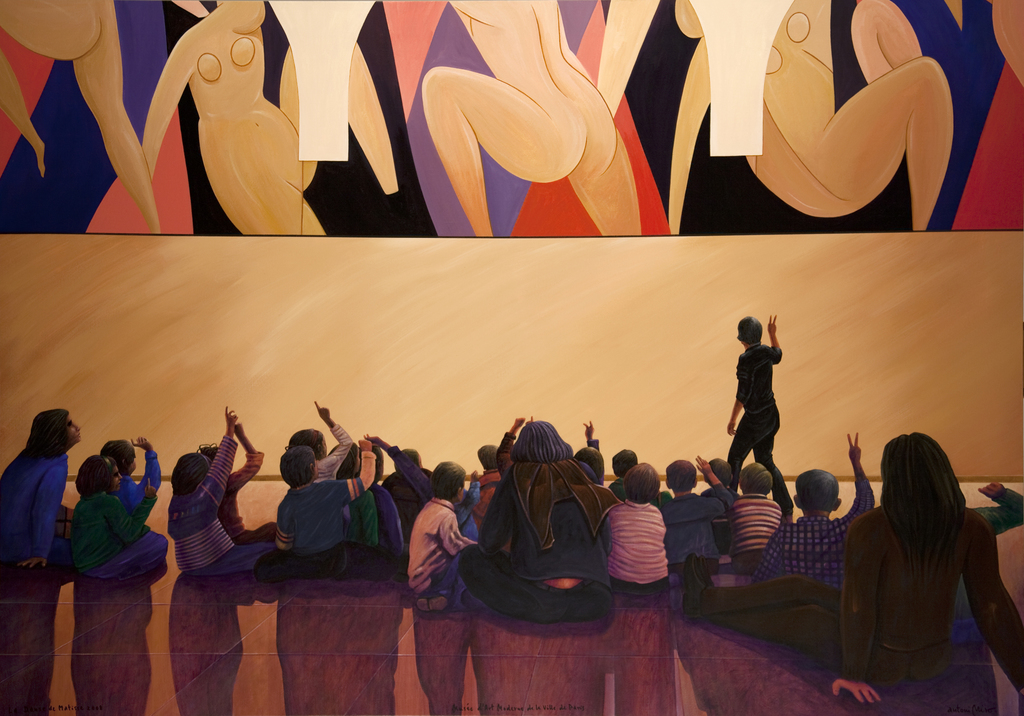

As a part of his reflective exercises regarding museums, this work depicts an act of aesthetic reception in this indoor scene. It is a painting that eschews the critical approach found in the rest of the series, giving a clearly hopeful vision. It could not be otherwise given the referent, La Danse — by Matisse, the archetypal fauve artist. Here, it is used to link it with free, unfettered learning by children.

The origin of the theme of La Danse lies in Matisse’s 1906 painting Le bonheur de vivre [The Joy of Life]. It depicts a bucolic scene in which six human figures dance gracefully in a circle in the centre of the painting, behind the figures in the foreground. Four years later, Shchukin commissioned two panels (Dance and Music) to deck the walls beside the staircase of his Moscow mansion. Here this vision is decomposed and the landscape figuration — an Arcadian fantasy with trees, animals, and the sea in the background — was eliminated.

In the two versions of La Danse at the time — the one at the MoMA and the Hermitage version, one can see the figures (now reduced to five) dancing in a circle and almost reaching the limits of the canvas. In the versions commissioned in 1931 by C. Barnes, this effect is taken further, with the figures often extending beyond the canvas. This boosts the visual dynamism of the picture and helps understand the situation depicted as generalised, which turns into a mere explicative fragment.

Of the three pieces made to decorate the living-room of the Russian chemist and modern art collector, two are now to be found in Paris’ Palais de Tokyo. This is because the works did not fit the vault and windows of the living-room, and were not to the client’s taste. The third work still graces the main hall of the Barnes Foundation in Pennsylvania.

The scene painted by Miró is the result of a given framing of the first two works, which are in the Paris museum. It also involves cropping of the top and sides, but the visual field below is opened. The painting comprises three horizontal strips, all more or less the same width. The top strip depicts the aforementioned work by Matisse. The sitting children and their teachers occupy the bottom strip. Both the top and bottom strips share two essential features: they are inhabited by figures in action and the shadows overlap with them, helping to visually articulate the whole. The middle strip is different — it has a strongly illuminated neutral background in which a teacher or guide explains the work.

Thus the object is linked with the real situation of the appreciation of the work. It does not matter whether one or two figures appear in the bit the children are being asked about. They are being invited to another type of request of a qualitative kind.

One should note the work is far-removed from the use of the pictorial element that Miró employed back in the 1980s in his Pinteu Pintura [Paint Painting] series. In this new period, Miró does not decontextualize a fragment, or figure of a canonical work to create a different narrative in which the meaning is changed, with the intention of an ironic recomposition. Instead, the repainted work is left unaltered save for the cropping of the frame. The result is it becomes a passive agent in the new creation. In other words, it does not deconstruct and recreate the original to give the spectator a new, different interpretation of given aspects brought from art’s canonical works.

Santiago Pastor Vila