A painting of stories

Santiago Pastor Vila

Despite what the title might suggest, we do not want to refer in this text to a kind of adaptation of the nineteenth-century genre of history painting. In fact, we know that a good part of the recent production of Miró, a collection that is shown to us now and here, could continue to be registered today in the Chronicle of Reality.

It is also clear that this movement, which no gender, whose name was coined by Aguilera Cerni more than fifty years ago, is on the path that comes from social realism, which despite being initiated also in the nineteenth century, is part of a tradition that is closer to highlighting the living conditions of society, denouncing especially the hardships and abuses, than to build a story full of great institutional deeds.

We want to talk, instead, of the reasons that motivate the artist to put an enormous diversity of stories before our eyes. Of the intentions that take it, in short, to paint scenes located in distant places that, for what they have in common with each other and with those that we have nearby, do not seem strange to us.

No one can ignore that, with historical progress, social advances do not come suddenly, or spread widely. There are always those who wait, or who demand radical changes so as not to despair. Some are, for example, beggars who roam the European cities praying for aid to all. The others, those who manifest themselves claiming springs everywhere. In both cases they are part of the repertoire of characters that usually populate the artist's paintings. They are a central part of the reality of which you want to make a chronicle, of a superior character to that of the media, yes, but with the same communicative effectiveness and almost with equivalent immediacy.

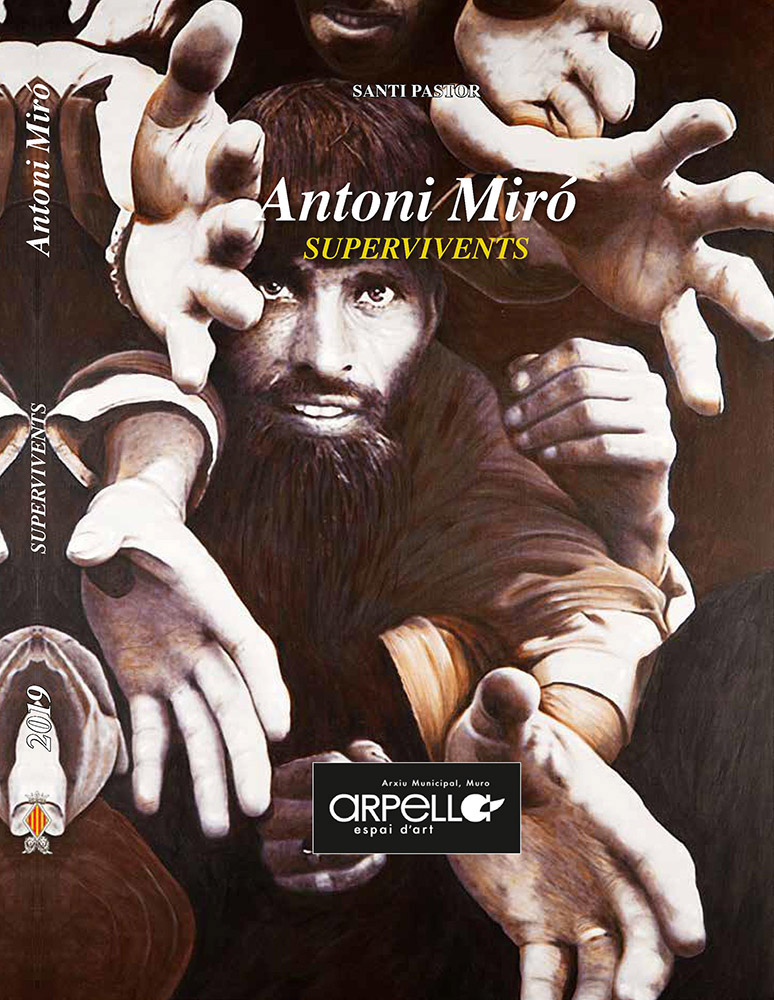

All together are truly survivors. Survives both who suffers the inclemencies in a hostile world and who hopes to reverse the sense that they have acquired the most serious vectors of discord. They equally and vitally use an approach with which to safeguard their integrity, either from the level of mere subsistence, or from a desire for the pursuit of fairer ethical milestones.

The look that begs for alms the central character of his work Survivors (2015) that lies under a sea of hands explains everything: we have to help, but we will not have enough to start, there are too many to do. It passes in an equivalent way with the valuation of the action contrary to the bend that can be seen in the pictures of the Mani-Fiesta series. There is a proclivity to change within society, but it can not be affirmed that we are already in front of new scenarios. As so many times, the reflection that the artist develops involves associated an intention to change the state of things.

It is admitted that history is nourished, with the passage of time, with the most relevant shared facts, and, often, unfortunately painful. With the stories of each citizen, the filter of relative importance can not be established so clearly. What is it, or is it not, for everyone?

However, there may be an agent that observes what surrounds it, reacts sensibly and politically, and initiates a dialogue showing a determined vision that detects the trace that a certain person leaves within History. This is what Antoni Miró does in a certain way: a reconstruction of the shared destiny illustrated with the sufferings and prowess of many; an exercise of composition integrating particular situations from everywhere to speak in general about the world now. With this inductive logic, a lot of diverse images constitutes a mosaic that explains in a certain way what has happened and happens.

But we have already said that the author's painting is not really about History. And this is the case even though it does not accept the end of this, as Fukuyama advocated. For the painter, liberal democracy is not a final and unbeatable stage. As we have said, he worries, however, about the ravages that are a consequence of fierce capitalism. That being the case, it puts together a whole bunch of stories to reflect a side of our shared reality that runs the risk of being silenced with indolence.

But, also with intensity, the interest for the denunciation is combined, as it has been exposed, with the one of the admiration. Despite not being exempt from criticism, the Museums series exemplifies in a very clear way the affection for the masterpieces and the great artists that have produced them. In it, again, as in the painting paint series, the relationship between looking and doing, between knowing and acting, between what is already and what is to come, although being a debtor of the lesson of the past, is addressed. When a painter copies the masterpieces to a gallery, it is no longer with the will to refer to the object first (the battle, for example), but to reproduce the subsequent mediation action. However, perhaps other more complex strategies, such as manipulating the elements based on partiality, incompleteness, irony, delocalisation and combinatorics ... can constitute a new, different mediation.

Probably the column of Trajan, a beautiful contrapicted image of which was the subject of one of the paintings of the painter of the year 2004, constitutes the clearest canonical referent of sequential commemorative narration. The national museums of art, especially the halls where they show the great paintings of history of the XIX century, can be understood as well, in spite of being smaller the number of scenes, focusing on the most important, to which, on the contrary, the degree of detail of the representation is increased.

Thus, in painting it, or in acting equally with Velázquez's Lanzas, as it did before, the artistic action is not directed to reproduction, but rather it leads to the aesthetic reflection on new significant possibilities of the object and the scene at this point, surrounding them with a critical transforming role. Almost two millennia after being erected in Rome, can we imagine how the course of events would take off? What part would we consider suitable to commemorate? Should not we report many episodes?

Fortunately, along with that cry of generalized denunciation, often drawn from the drama of the personal stories of many and with which it forms a gravely harsh vision of today's world, we find the work of the artist another song of hope that takes shape from the longing for a past time and the recognition of the beauty of the legacy that has reached us.

We can refer in this sense to the works of the series “Costeres i Ponts”, which, despite being references to great achievements, focus on the field of the own culture, and close, far from the great stories, and have a character aesthetic that shares the descriptive, representational approach to reality and the tension that is the result of the special framing and the multiple modifications that have been made.

Above the bridge of San Jorge de Alcoy many of their looks are focused, using it as a totem that contains the keys of a local spirit, a kind of Alcoyano Volksgeist. We believe, moreover, that the bridge does not in vain employ its symbology as an artificially created nexus with much effort that challenges the natural disunity between two parties. This beautiful artifact is a survivor who, unfortunately, passes through the ideas that sponsored his modernity. I want to imagine that by repainting them they start moving again.