Taxonomías de la producción de Antoni Miró

Santiago Pastor Vila

Es conveniente empezar cualquier relato que tenga cierto afán clasificatorio, como este, explicando los criterios que se emplearán para establecer la categorización y situando en términos generales el objeto sobre el que se debe producir.

La materia que nos ocupa es la valiosa producción pictórica de Antoni Miró. Esta ha logrado una dimensión extraordinaria después de seis décadas de continuada dedicación al arte. Solo por eso ya habría que establecer ordenaciones diferenciadoras en agrupaciones de diverso tipo que se refieran a uno o más criterios distintivos, como por ejemplo periodos, temáticas, técnicas, lenguajes, estilos… En este caso, por suerte, esto ya lo ha hecho el artista premeditadamente: con la meticulosidad que le es connatural ha decidido organizar su trabajo pictórico dentro de varias series cuyas características han sido fijadas previamente y sostenidas estrictamente durante todo su desarrollo.

Estamos delante, pues, de una obra completa que a pesar de ser muy extensa ya se nos presenta articulada en varios bloques que se diferencian del resto de forma evidente. En cada uno, la temática a la que recurre y el lenguaje que utiliza son muy diferentes al resto. A lo largo de un mismo periodo de duración considerable (varias veces alrededor de una década), genera obras y se mantiene fiel a un determinado modo de hacer. En cierto momento, los intereses cambian y su sensibilidad lo lleva a modos de pintar diferentes, y empieza otra nueva serie. Estas disrupciones no impiden que haya determinadas cuestiones que se traten transversalmente en varias series.

Precisamente por esto último, además de caracterizar sucintamente las diferentes series que construyen su carrera, es fundamental identificar los cuatro ámbitos de reflexión que aborda el artista con más frecuencia. Podremos comprobar cómo estos atraviesan las distintas series presentando una modulación variable pero simultáneamente, manteniéndose en esencia.

Cómo procede el artista, tal y como se acaba de definir, es fruto, evidentemente, de su fuerte determinación personal. Pintor desde el principio por decisión propia: así podría decirse condensadamente que ha sido Antoni Miró. El breve pero acertado texto que ha preparado Sofia Bofill para este catálogo razonado explica claramente esta cuestión clave y sus consecuencias. Esta firme voluntad ha sido, de hecho, el impulso principal que ha nutrido su trayectoria artística desde el origen. Tanto es así, que no pocas de todas las consideraciones que Fernando Castro ha incorporado a su brillante y extenso escrito en relación con la evolución de la carrera artística de Antoni Miró y los planteamientos estéticos que la sostienen también tienen que ver en cierto modo con este propósito fundamental y de partida. Y es que esta dedicación tan intensa a la pintura, continuada y decididamente voluntaria, en definitiva, califica de buena manera y diferencia la posición vital tan singular de Antoni Miró hacia el mundo.

De acuerdo con esta temprana y decidida orientación hacia la acción pictórica, ha ido edificando su trayectoria: es una declaración de principios que no ha perdido vigencia durante más de sesenta años ejerciendo como pintor y siéndolo. Mira el estado de las cosas en el que se presenta la realidad, consciente de que los efectos que resultarán de su análisis sensible acabarán adquiriendo inevitablemente el cuerpo de obra pictórica. Por eso, entre otras razones, las disciplinas artísticas comparten nombre con los resultados que proporcionan, y, al mismo tiempo, con el término pintura nos referimos a la forma de actuación, de trabajo y a los objetos que se derivarán de ella. Pero, además y especialmente con las acciones de tipo artístico, puede llegar a sustanciarse lo que un individuo pretende ser esencialmente durante toda una vida.

Ha podido crear insistentemente una trayectoria prolífica de amplio espectro. El deseo de sumergirse en la pictórica ha sido un factor invariante de relevancia extraordinaria. Aun así, no es el único hilo conductor de su carrera; no en balde, la urdimbre del tejido mironiano es múltiple. Siempre ha pintado manteniendo posiciones reivindicativas, de rechazo en ciertas ocasiones y de apoyo en otras, y ha ido tramando su discurso entrelazándose. Como ya se ha dicho, las sucesivas elaboraciones se agrupan en series según intereses temáticos de carácter más concreto y estrategias de elaboración diferentes.

En cuanto a la temática, unas veces, por ejemplo, las obras destacan las denuncias de injusticias en todo el mundo (hambre, guerra…); otras constituyen alegatos de defensa de la cultura e identidad propias, y otras representan homenajes a los maestros de la historia del arte occidental desde el Renacimiento o a intelectuales, poetas y artistas del ámbito catalán. Muchas reproducen manifestaciones sociales. No pocas celebran la belleza y sensualidad femeninas, o remiten al calor del Mediterráneo o del Caribe. Varias apelan al riesgo de destrucción de la naturaleza. Esta multiplicidad se puede mostrar de forma compacta y explícitamente coordinada dentro de una misma serie, pero también llega a ser reconocible como una insistencia continua implícita que afecta a varias series diferenciadas.

En muchos de los casos, además, los alcances del espacio-tiempo de los referentes son muy diferentes. El artista ha aludido recurrentemente a la batalla de Almansa, y, cuando acontecía, a la Guerra de Irak. Ha puesto de manifiesto la primavera árabe y también la valenciana. Ha incorporado figuras e imágenes de las obras de Joan Miró y del Bosco en el mismo cuadro, y lo ha hecho también en otros con las de Velázquez o las del autor de tebeos Ibáñez. Ha enfrentado a un rinoceronte africano con la central nuclear de Cofrentes. Todas estas relaciones de elementos que comparten rasgos o que son ajenos entre sí pero que pueden construir un nuevo significado a pesar de formar parte de ámbitos muy diferentes son fruto de una predisposición a establecer analogías fundadas en la ironía.

En cuanto a los lenguajes que ha cultivado el pintor, hay que decir que, salvo una primera fase de carácter expresionista, se ha centrado en la figuración y ha avanzado sucesiva y progresivamente en el grado de realismo, de forma que ha llegado a un hiperrealismo en el cambio de milenio.

El realismo social, o más precisamente la crónica de la realidad, es el movimiento dentro del que habría que inscribir su producción de finales de los sesenta y de los setenta. En los ochenta, hace los que hemos denominado collages doblemente pictóricos —pintados y referidos a la pintura— en los cuales, por cierto, nunca abandonará el remarcado de la silueta de los fragmentos, como dibujándolos. En la década posterior se abre la puerta a una figuración de carácter onírico. El siglo XXi es, en cuanto a la obra de Miró, el del hiperrealismo, y también es cuando se reencuentra con la voluntad de plasmar sobre el lienzo los caminos más duros que abren la globalización dentro de la historia, como hizo treinta años antes con otra intención comunicativa menos fiel a la apariencia real.

Durante esta evolución, las técnicas de representación han sido muy variadas: tablas y lienzos pintados con acrílico u óleo, pero también con limaduras de metales y otras materias, y muchas veces incorporando otros recursos como por ejemplo el collage, la aerografía u otros. Obras clave han sido conformadas como objetos por el hecho de haberse modificado en cuanto a la calidad de apoyos o configurando piezas que, aunque pictóricas, se acercan al campo de la escultura. Otras se pintan mediante la operación de disponer directamente un objeto tridimensional sobre el plano de referencia.

Las dimensiones temporal y temática —es decir, la duración de la carrera y el alcance de intereses— son, como se ha dicho, de extensión considerable. Pero, además, hay otras variables que introducen un grado de multiplicidad extraordinario. Así, la obra de Antoni Miró aumenta decididamente en su polimorfismo. Sin embargo, puede organizar por series cuyas características son indudablemente reconocibles en los cuadros que las integran. Los factores que enmarcan las obras dentro de cada serie responden a una estrategia comunicativa determinada. Según el lenguaje que emplee, la densidad de signos que disponga y el factor de relación que establezca, estamos ante una u otra.

Por ejemplo, era habitual que en los setenta canalizara sus ansias de denuncia del imperialismo yanqui representando solo un personaje, o incluso un fragmento de él, involucrado en una situación violenta, ocupando un lugar primordial de la composición, a veces casi saliéndose de los límites, y representado con ecos fotomecánicos, vinculado, a la vez, con un objeto que represente la sociedad de consumo (un dólar) o la guerra (un fusil).

En la década posterior, la reivindicación de la tradición de la pintura occidental se genera reproduciendo con cuidado los cánones de representación que han sido propios de cada uno de los estilos pretéritos de las épocas de sus homenajeados. Pero la esencialidad de los setenta es sustituida por un tipo de horror vacui revisado que pone de manifiesto la superposición intertemporal y las distintas autorías. La asociación conceptual es menos directa que antes. Los títulos de las obras adquieren un papel fundamental en cuanto a la capacidad de completar el mensaje de la obra, función que ya nunca se abandona.

Los noventa suponen la llegada a una madurez de estilo. Es un momento de elaboración de una nueva forma propia que conjuga una figuración realista con la proposición de unas ideas sugerentes y evocadoras que responden en relación con la realidad solo en el plano conceptual. Como en muchos juegos de palabras, la ironía y el recurso a lo absurdo son la base de la creación del discurso de ese momento, pero sin huir de referir situaciones concretas por esta razón. La inverosimilitud se pone a disposición de la denuncia, porque así se sorprende más eficazmente al espectador que poniéndole ante los ojos un cuadro que rememora lo que tiene delante día a día. Como pasa con la poesía visual, hay que aislar, tal como él hace, los signos de cualquier elemento que les quite la intensidad comunicativa.

Durante los últimos veinte años, por una parte, la crueldad urgente de la realidad impulsa al artista a no aplicar filtros sobre lo que ve y deja como función principal, además de la selección del encuadre, la transposición de los hechos a la pintura directamente y significando los detalles que más connotaciones aportan a la escena. Esta forma de hacer historia se complementa con otro interés: la valoración de los elementos que nutren su repertorio de memoria y también de sus referentes culturales. Los puentes de Alcoy o un retrato de Estellés son motivos que inducen a la acción reflexiva respecto al curso vital mediante la pintura.

Este sucinto análisis de conjunto de su trayectoria se debe complementar necesariamente con unos comentarios específicos alrededor de cada una de las series con las que se construye. Desde los trabajos iniciáticos de finales de los años cincuenta hasta las últimas obras de 2020 que se han incorporado en este catálogo razonado, se pueden contar ocho: “Opera Prima” (1960-72), “Amèrica Negra” (1972), “L’Home Avui” (1972-74), “El Dòlar” (1973-80), “Pinteu Pintura” (1980-91), “Vivace” (1991-2001), “Sense Títol” (2001-13) y “Sense Sèrie” (de 2013 en adelante).

Descripción sucinta de las series

Los primeros trabajos de los últimos años cincuenta (1957-59) conforman un “periodo inicial” cuyas obras se podrían clasificar como tanteos expresivos de aproximación a la disciplina.

Las pinturas de comienzos de la década siguiente siguen estando imbuidas de este carácter iniciático, pero ya dejan entrever algunas de las claves que más tarde caracterizan su producción madura. Los primeros gritos de denuncia social se prepararon entonces, al llegar a la que será la primera de las series constituida formalmente, denominada “Opera Prima” y que se extiende desde 1960 hasta 1972. La selección de la obra El bevedor, realizada en 1960 como pieza inaugural de este catálogo razonado, quiere significar este posicionamiento. Con claras resonancias neorrealistas, se refiere al sufrimiento particular de un desfavorecido.

Otras obras de aquella primera fase constituyen un repertorio diverso que mezcla acciones de aprendizaje (bodegones y otros ejercicios, como una bella representación de máscaras) con otras dirigidas a representar el entorno vital del artista en su primera juventud. Son ejemplos de ello alguna escena urbana de Alcoy, mostrada como una ciudad industrial implantada sobre una orografía complicada, con claros rasgos diferenciales que la alejan del aspecto común del resto de poblaciones valencianas en esos momentos. O también algunos retratos de personas próximas, que sirven para adentrarse en la representación figurativa de carácter psicológico. Durante esa época complementa las pinturas de figura con unos apuntes esquemáticos de dibujo de línea, indagando fundamentalmente sobre las claves del escorzo.

Dentro de esta primera serie hay varias subseries integradas, como veremos a continuación, constituyendo un conjunto caracterizado por el afán de experimentación en términos plásticos y la diversidad temática.

Dentro de las subseries “Les Nues” (1964-66), “La Fam” (1966) i “Els Bojos” (1967) se agrupan obras de carácter expresionista y de clara constitución matérica. Se presentan como conjuntos de fuerte componente telúrico, preparados con texturas muy marcadas y con una paleta muy corta y poco luminosa, con resonancias de las pinturas negras de Goya.

Prosigue con unas “Experimentacions” de tipo abstracto y formalista, que consisten en la muestra de sistemas compositivos basados en la alternancia cromática dentro de redes modulares.

Sin duda, las subseries “Vietnam” (1968) y “L’Home“ (1968-71) son las más significativas de la década y tienen un claro carácter de transición hacia el que será su enfoque más habitual: el realismo social. Todavía las crea empleando recursos expresivos que las mantienen alejadas de lo que podría ser una figuración plenamente realista. Aun así, suponen un posicionamiento crítico contra las injusticias que había en el marco social del momento, que se adentraba en la era tardocapitalista y del avance de la globalización. No se incorpora estrictamente de momento al lenguaje propio del movimiento de la crónica de la realidad, pero los intereses temáticos sí que son los que concentran su atención.

Las obras se componen combinando figuras esquemáticas y signos de varias clases con planos de color intensos, rojos y negros predominantemente. El uso del aerógrafo y otras técnicas no tradicionales dota a las representaciones de un aspecto nuevo, actualizado, parecido al que se usa en los medios de comunicación de masas y la publicidad. Hay un discurso narrativo en muchos casos que simboliza el paso del tiempo mediante secuenciaciones de escenas.

El 1972 realiza la serie “Amèrica Negra”. El título es explícito y deja claro que está dedicada a los afroamericanos. Lo hace en tono reivindicativo: el tema que denuncia el artista es la carencia de igualdad efectiva en cuanto a los derechos y oportunidades que se sufría en los EE. UU. todavía durante los años setenta a pesar de los logros de la década anterior gracias al trabajo liberador de Martin Luther King Jr. contra el racismo. Cuestiona, en definitiva, que, en el conocido como país de las libertades, estas lleguen realmente a todos los ciudadanos.

Realiza las obras sobre tablas de formato mediano, generalmente cuadrado. Desarrolla un lenguaje pictórico que pretende emular la imagen de las fotografías periodísticas, impresas mediante sistemas cada vez más sofisticados. La prensa se hace eco de un problema que ocurre en un punto concreto del mundo y que, en cambio, se difunde globalmente. Este es el origen de la información, y la condición misma de situación real que está ocurriendo al tiempo que se produce la obra es lo que hace que se opte por este paralelismo representacional que es la crónica de la realidad, lo que aporta a la obra una alta eficacia comunicativa y un carácter de inmediatez, de narrar críticamente lo que afecta a la sociedad de consumo.

Los enfoques elegidos, muchos primeros planos en los que parte de la figura queda fuera del marco, aumentan la violencia de la escena. Los personajes y la dura situación en la que se encuentran es lo que importa; no hay información que quede al margen, que forme parte de un fondo. Caras, cuellos, puños… todos los elementos se nos ponen delante de forma virulentamente directa. El modelado del volumen se consigue mediante la colocación gradual de formas cromáticamente planas, como pasaría con la serigrafía. Los rojos y los azules predominan sobre los elementos más significativos, y se completa el resto de la composición con grises y negros. El artista incorpora a las obras varias tramas, como las de los cartonajes perforados para las máquinas de jacquard o punteados muaré, que complementan la escena visualmente. Esta última táctica ha facilitado que las imágenes conseguidas se situaran directamente en ese momento. Esto último se puede apreciar, por ejemplo, en la obra titulada Lluita d’infants, en la que sabemos que nos situamos pasados los sesenta no solo gracias a las camisetas o al peinado, sino a causa de estos elementos.

La esencialidad de las configuraciones aparece a veces intensificada por la existencia de unos halos que se suceden alrededor de las figuras. El tríptico Igualtat per a tothom es una clara muestra de ello. Se deja ver que el personaje central irradia con mucha potencia un mensaje de esperanza.

También en 1972 empieza a elaborar la serie titulada “L’Home Avui”, que dura hasta el 1974, dentro de la cual hay que destacar Herculusa i Daviet sobre el resto de las obras, puesto que constituye un tratamiento metafórico muy interesante de la denuncia del imperialismo yanqui, que se forma mediante el recurso a la representación de dos esculturas clásicas.

Las preocupaciones de carácter social se manifiestan mediante la consideración de la pintura como una herramienta reivindicativa. Aun así, se ocupa de otras funciones del arte relacionadas con la fruición, como demuestra por ejemplo el hecho de que no deja de preparar entonces dibujos eróticos de desnudos femeninos, además de las propuestas de denuncia política mencionadas.

El año siguiente, 1973, es el inicio de la que se podría considerar la primera de sus grandes series, “El Dòlar”, que lo tiene ocupado durante el resto de la década, hasta 1980.

Hemos calificado esta de gran serie por tres motivos, del mismo modo que las siguientes. El primero tiene que ver con la considerable amplitud temporal y el extraordinario volumen de producción. El segundo origen de grandeza proviene de la pertinencia de los intereses temáticos en cuanto a la actualidad y a la combinación de un alcance a la vez global (lucha anticapitalista) y local (reafirmación de los signos de identidad cultural que entiende el artista como propios). Pero es en el tercer aspecto donde reside especialmente la importancia: de forma muy evidente vemos que el pintor define con insistencia un código lingüístico personal. La figuración hiperrealista de los diversos elementos de las composiciones se articula de manera singular. El recurso a la ironía, tan propio de las corrientes críticas del realismo social y del pop de influencia británica, es capital, como lo era antes y seguía siéndolo para otros colectivos del entorno valenciano (Equipo Crónica, Equipo Realidad…) o para el propio Arroyo, por ejemplo. Aun así, se reconoce un modo de hacer específico en la obra de Miró.

El hecho de que se pueda diferenciar gracias a esta voz propia y que, a la vez, sus clamores compartan rasgos con otros que forman parte del contexto artístico reconocido más próximo pone de manifiesto el arranque de una trayectoria de primera madurez ya decididamente firme. Es, pues, en los setenta cuando podemos hablar de un Miró que empieza a hacerse ver de otro modo. Podemos decir que durante los primeros sesenta el ámbito de influencia de su obra era meramente local y que fue galardonado con varios premios. Durante la segunda mitad de esta década y los primeros años de la siguiente, ya no fue así. No solo avanzó gradualmente en el conocimiento del entorno artístico valenciano y español, sino que se fue implicando cada vez más intensamente dentro de este sistema. Muestras de esto son los liderazgos del Grupo Alcoiart y, posteriormente, de la galería casi homónima Alcoiarts en Altea. Este proceso de arraigo, unido al hecho de impregnarse de lo que era entonces el arte contemporáneo, viviendo temporadas y exponiendo en varios países europeos, como por ejemplo Inglaterra, Francia e Italia, donde formó junto con otros el Gruppo Denunzia, está claro que tenía efectos en cuanto a la elección de una posición personal como artista.

La subserie llamada “Dòlar-Xile” es muy característica de la serie que ahora nos ocupa. Es ciertamente extensa, de extraordinaria actualidad entonces, hecha justo después del golpe de estado de Pinochet y con rasgos representativos diferenciales que la singularizan respecto a otras denuncias contemporáneas. Los asesinatos perpetrados por los militares, las coacciones de las libertades, la dirección yanqui del proceso… Todos los elementos clave se muestran de forma diferenciada de otras propuestas críticas contemporáneas.

Como se puede suponer, dentro de esta serie el dólar es un símbolo esencial. Lo es a la vez de la dominación yanqui y del capitalismo. Hay una obra muy interesante que refleja muy claramente las claves de la mirada del artista hacia lo que representan estas superestructuras opresoras: Dòlar enforcat (1974). Sobre un fondo que simula un papel rizado se presenta un dólar estrangulado con una cuerda de tender, como si uno pudiera rebelarse contra el neoliberalismo. Estamos delante de una visión del dólar que amplifica las críticas que ya hizo Warhol antes, pero que pretende destacar cómo los efectos del mencionado dominio ya se habían globalizado con consecuencias graves.

Las guerras son uno de estos efectos perjudiciales. Una serie que buscaba ser una enmienda a la totalidad de lo que representaba el imperialismo estadounidense no puede estar exenta de denuncias sobre las guerras que la primera potencia mundial impulsaba en varios lugares. La de Vietnam, ya finalizada entonces, sigue siendo un referente; pero el artista se refiere también a otras nuevas motivadas sobre todo por el enfrentamiento entre bloques y por razones económicas. La dinámica bélica se representa de forma muy eficaz mediante una obra móvil: Sobre la processó (1975-76). Se superponen dos cuadros que muestran los bastidores por la parte posterior. Uno se fija en la pared y otro gira sobre este. Cada uno de los cuadrantes del rotatorio comprende el mismo fragmento, que consiste en parte del cuerpo de un soldado y su fusil. Este se alinea con la diagonal del cuadrante, orientado hacia el punto central. Al moverlo rápidamente, como pasa en los molinos, la presencia se intensifica.

La gravedad de los asuntos que trata el artista se puede ver contrapuesta con otros intereses que no por ello están exentos de carácter crítico. Por ejemplo, el erotismo y la belleza femenina se combinan con las denuncias del capitalismo y la guerra. La obra Una noia i un soldat (1974) es un paradigma de esto.

Un poco más tarde empieza a desarrollar el conjunto de su obra destinado a la cultura propia con la subserie “La Senyera” (1977-78). Especialmente con un trabajo fundamental dentro de su producción de aquella época, Llances imperials (1977), ocurre lo que ya hemos comentado arriba. Varios artistas se refirieron a la obra maestra de Velázquez para simbolizar el carácter de rendición que podía llegar a tener el proceso de democratización en España (Arroyo o Equipo Crónica son dos ejemplos de ello). Miró emplea el mismo recurso, pero centra su interpretación en el contexto de la articulación territorial del Estado español y se refiere al momento histórico que encaran los valencianos. Con esta pintura-objeto replantea el intercambio desigual: ahora el imperio va asistido de la lógica neoliberal, y el pueblo vencido puede entregarse por menos de lo que merece. Lo hace, además, manteniéndose en un plan intermedio entre las disciplinas pictórica y escultórica. Ninguno de los elementos corpóreos carecen de volumen, todos se modelan más allá de las dos dimensiones, no son un mero apoyo plano de la pintura, pero aun así todos se definen pintándose.

La segunda gran serie dentro de su trayectoria, “Pinteu Pintura”, se desarrolla a lo largo de los años ochenta: empieza el año inicial de esa década y finaliza en 1991. Se produce un cambio de dirección del planteamiento artístico muy significativo. La propia denominación de la etapa productiva ya nos coloca frente a una paradoja. Se podría decir que es una especie de amenaza, pero también que es una mera advertencia. Miró puede sugerir que se pinte pintura, aquella que ya se ha hecho e integra el canon occidental, y no cabe otra cosa. En definitiva, que la historia del arte sea el referente y que la tarea de entonces sea revisarlo, deconstruirlo y reelaborar un nuevo significado mediante significantes que son muy conocidos. Por otra parte, puede estar recordando que no puede hacerse otra cosa que pintar pintura, la que conforma, como hemos dicho, un catálogo valioso que nos ha sido legado.

Sea de una manera u otra, estamos ante un planteamiento metapictórico. Se hace pintura de la pintura o, matizando, se hace pintura en plena posmodernidad, mucho más tarde de haberla asesinado, recorriendo a los referentes clásicos desde el Renacimiento. El objeto de análisis ya no es la realidad, es una cualificada elaboración anterior del mismo tipo. Con esta forma de reelaboración, varios fragmentos de obras clásicas se recombinan y generan un nuevo mensaje. Estos collages se componen irónicamente. En muchos de ellos, el artista sigue comunicando en tono de denuncia, pero en otros se mantiene en un plano de reflexión sobre la disciplina pictórica o, incluso, le rinde homenaje.

Continúa vehiculando críticas de carácter político con obras como por ejemplo la pintura-objeto Dídac d’Acedo (1980), que representa una selección del retrato de Velázquez, que es objeto de una transformación que hace al personaje más siniestro, o las obras Díptic democràtic (1986-87) o Qui té por (1988). Son fundamentales dentro de este primer grupo temático dos obras: Retrat eqüestre (1982-84) y El misteri republicà (1988). En la primera, un recortable del conjunto caballo-jinete se muestra iconográficamente amenazante. Se toma como símbolo de dominación y se dispone sobre un fondo texturado como un papel blanco arrugado. El tratamiento plástico del elemento es más directo que en su referente histórico. Se perfilan las formas y se endurecen las gradaciones: se acerca al lenguaje del dibujo de cómic. Esta no es la única vinculación con la cultura popular. Muchos logotipos de marcas de empresas multinacionales, del sector de la automoción mayoritariamente, se estampan sobre la nalga del caballo. La cincha con que se sujeta la montura se presenta como una bandera española.

El pintor traslada una opinión crítica respecto al consumismo y el sometimiento a las exigencias de las grandes empresas multinacionales. Su visión del Estado se centra en su capacidad como ente administrador de la coacción y la violencia y lo pone de manifiesto con la presencia de dos elementos simbólicos: el as de bastos y la cabeza de un cuervo. La displicencia con la que trata al personaje histórico del conde-duque de Olivares como agente represor en Cataluña se completa con el hecho de presentarlo fumando y con un parche en uno de sus ojos.

En la segunda, la crítica política es más velada, y los referentes artísticos, más próximos en el tiempo. Ante una situación que el artista considera enigmática como es el abandono del proyecto de recuperación del republicanismo, perfila una obra articulada alrededor de cuatro elementos. La base es Los misterios del horizonte de Magritte. Desaparecen las lunas y se complementa con una franja superior por un collage de recortes de prensa internacional no exento de formas propias de las composiciones cubistas, como por ejemplo la botella de vidrio, y lleno de noticias referentes a procesos reivindicativos y de liberación. Con esta estrategia se contextualiza el mensaje dentro del ámbito de la actualidad política, como si este alimentara las preocupaciones de los personajes. Sobre este nuevo campo, el artista introduce dos elementos más. Uno es una reproducción volteada del retrato de Carlos III pintado por Mengs. Es muy interesante cómo este se dispone dentro de la oscuridad, con los ojos dirigiéndose hacia el espectador, mostrándosele a pesar de no ser percibido, metafóricamente, por los otros personajes. El otro es la faja que los rodea a los cuatro, como sugiriendo que les afecta aunque sea indirectamente, como si no pudieran desprenderse de la tradición histórica.

Por lo tanto, durante la década de los ochenta, la crítica política se vehiculó mediante la reformulación irónica de varios elementos o fragmentos reconocibles del repertorio formado por las obras canónicas de la historia del arte occidental de los últimos cinco siglos. Los actos de selección y combinación proporcionaron entonces las claves más valiosas de este proceso comunicativo basado en ofrecer una representación sucesiva más o menos literal de parte de un antecedente, nunca de la totalidad.

En cambio, los signos con los que construye las obras de la década de los años noventa son los objetos de uso cotidiano, ya no los referentes de la alta cultura. Con la serie “Vivace” (1991-2001), el artista complementa el tono crítico característico de su producción con otra visión que celebra varios aspectos que regala la vida.

Así, las denuncias solo se mantuvieron en parte, focalizadas en los temas que constituyen una constante a lo largo de su trayectoria, como por ejemplo el imperialismo yanqui, tal como se muestra en el psicodélico Interludi (1998). Sin embargo, en esta etapa estuvieron frecuentemente dirigidas a las reivindicaciones ecologistas. La costa mediterránea se encontraba ya entonces más que asediada por la depredación urbanística. Los hábitos de consumo provocaban un aumento insostenible del volumen de desechos plásticos. Ambas situaciones hacían intuir la catástrofe que venía.

A pesar de este pronóstico terrible, la producción de esta serie es muy colorista y persigue mostrarse a quien la admira agradablemente y lejos de las complejidades propias de fases anteriores. En el cuadro Costa Blanca (1993), el brazo de una excavadora se presenta de forma amenazante, y una pequeña lata de Coca-Cola sirve para vincular la operación de destrucción con las maneras de consumo desbocado que se habían importado desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial de los EE. UU. En el cuadro Parc natural (1993) se representan dos fajos de envases plásticos, pero no solo eso. Después de una mirada escrupulosa descubrimos toda una serie de mensajes a manera de marca comercial claramente contestatarios (Verí Good, Dona Casa…) y cómo los fracasos de la sociedad (¿por eso hay una oreja cortada, como si fuera la de Van Gogh?) pueden llevar a la muerte, como indica el testimonio de un cráneo.

Por otro lado, la vitalidad se expone ante el espectador principalmente a través de la figura femenina desnuda. Es así en Tros de Cuba (1999) y también en Horitzó roig (2000), dos cuadros en los que la belleza y la sensualidad de unas jóvenes cubanas se nos ofrece sobre un intenso fondo azul de forma muy diferente. La primera, como una presencia real que sale de los límites y se intensifica; la segunda, casi como una apariencia onírica solo dibujada.

Pero no es solo mediante el erotismo de unos desnudos mediante lo que se refiere al vitalismo. El viaje, como un proceso que conduce al conocimiento de uno mismo gracias al alejamiento y el reconocimiento de los otros, es otro motivo simbólico de lo que es la vida. Una taza de café humeante, un noray expectante al lado de un muelle o una maleta medio abierta son tres elementos que se pintan de manera preciosista, como si se tratara de objetos de cierta relevancia, aunque son simplemente evocadores.

La relación propuesta por Antoni Miró hacia la naturaleza está exenta de generación de impacto. La ligereza es el factor esencial. Las bicicletas son un paradigma de esta interacción ideal. Son mecanismos casi transparentes, formados por elementos lineales que casi desaparecen al superponerse en el medio. Pero sobre todo son artefactos que se mueven gracias a tracción exclusivamente humana, sostenibles, que se oponen a las pesadas máquinas con las que destruimos el entorno que nos acoge.

El artista utiliza las bicicletas como paradigma ecológico y las transforma en sus composiciones de varias maneras. Sigue estableciendo contactos con elementos de la historia del arte, por ejemplo, cuando personajes del Gernika hablan entre sí sobre una bicicleta que se mueve en el umbral entre el mar y el cielo, en Diàleg (1996). O cuando son los aparatos voladores de Leonardo lo que hace que una bicicleta que ilumina el camino con una luz picassiana se mueva, en Bici aèria (1996).

Con el cambio de milenio, la visión artística recupera su vertiente criticopolítica y, además, su alcance mundial en cuanto a sus intereses. La serie “Sense Títol”, con la que rebasa el primer decenio hasta 2013, supone una revisión del arte de denuncia que lo mantuvo ocupado tres décadas antes.

Las tensiones producidas por las migraciones al primer mundo son uno de los temas hacia los que se dirigen sus reflexiones. También constituyen otras pruebas de este redireccionamiento las obras sobre el atentado del 11-S en Nueva York, como por ejemplo los lienzos Manhattan people (2002) y Escac i mat (2004). Asimismo, los conflictos del Oriente Medio, especialmente la Guerra de Irak, son objeto de representación.

Durante los años setenta, el tema bélico ya fue capital en la producción artística de Miró. Como es sabido, Vietnam fue objeto de una subserie, y conflictos del entorno árabe, como la lucha contra Israel en los altos del Golán, fueron temas de otras obras. Aun así, en esta nueva revisión de los conflictos armados se abandona la clave simbólica, el esencialismo y la manipulación visual, y se opta por un hiperrealismo con el que se retrata crudamente la complejidad de las situaciones. En Desert de Kuwait (2004) y Tortura BBA (2010) se reproducen imágenes de prensa, fidedigna y directamente con la crueldad que las caracteriza; solo en algunos casos se introducen distorsiones de naturaleza irónica, como podría ser el reemplazo de la bandera estadounidense por unas señeras.

La mirada del pintor hacia los sufrimientos de la contemporaneidad no apunta solo a las guerras. La pobreza es el otro ámbito que a menudo refiere. Todavía en época de bonanza económica, refleja numerosas escenas en las que son protagonistas pedigüeños que esconden el rostro mientras alargan el brazo rogando por una limosna en distintos lugares turísticos de ciudades en toda Europa. Todas son ejemplo del vivo contraste entre carencia y opulencia. Otros muestran un escenario más amplio pero igualmente incidente en la miseria, como hace en Gran Madrid (2010). En esta obra se presenta en primera instancia un poblado de barracas habitado por el lumpen, aunque, tras una mirada atenta y detallada, proporciona adicionalmente varios mensajes incorporados mediante la alteración singular (pintadas en los muros) y la complementación por la disposición de elementos simbólicos (bandera de la II República, por ejemplo). Modificar algunos elementos del sistema o añadir otros ajenos son las dos estrategias que emplea el pintor para ampliar los efectos comunicativos de sus creaciones. Como estas acciones son solo levemente aparentes, el espectador accede a ellas después de haber observado el cuadro con cuidado. Antes de esto, asume, ilusoriamente, que está ante la reproducción de un fragmento de la realidad que le llega sin mediación.

El artista también aborda el choque de civilizaciones. Burka políptic (2010) es tal vez la obra más destacable en este sentido. De raíz claramente warholiana, cuestiona la indiferenciación con la que se trata a las mujeres en Afganistán. Como una máscara, de manera indeseada, anula la diversidad de caracteres, se configura una serie de una misma cabeza cubierta combinada con variaciones cromáticas para criticar, precisamente, esta homogeneización obligada. Hemos calificado de entrada esta composición de warholiana por la influencia en cuanto a configuración y operación transformadora del motivo; aun así, durante esta etapa de la trayectoria de Miró, su producción está fuertemente relacionada con el problema de la reproductibilidad y el aura de la obra de arte, ambos conceptos puramente benjaminianos.

Está claro que Benjamin estaba tanteando los efectos derivados de la irrupción de los nuevos medios técnicos: la fotografía y el cine. Las oportunidades que ofrecían los nuevos lenguajes tenían que oponerse a los riesgos de la pérdida de los valores que habían calificado hasta entonces las obras de arte. Pues bien, en varios planos de análisis podemos evaluar esta problemática en la obra de Miró del siglo XXi.

Uno de ellos tiene que ver con una inversión de sentido: si la fotografía ponía en cuestión la pintura como herramienta de representación de la realidad desde antes de la mitad del siglo XiX, ahora se plantea de forma contraria: que la pintura puede aumentar las posibilidades significantes, especialmente en la vertiente simbólica, de imágenes de naturaleza original fotográfica. Otro afecta a las condiciones de artisticidad de la obra como objeto material, el aura.

En relación con este último aspecto, en ocasiones se muestra una pieza capital de la tradición de la pintura occidental repintada de una forma particular. Nos referimos a obras como Pintar a Botticelli (2003), Observant Murillo (2006), La famosa Gioconda (2008) o La lliçó d’art (2009). En todas, de la tensión entre realidad y representación se pasa a otra que vincula una representación primera canónica (de la realidad) con al menos otra que ya no se circunscribe meramente al referente, sino que incluye el ambiente que lo rodea, el museo, y en la que hay otros espectadores que lo aprecian. Es decir, el cuadro incluye una elaboración pictórica anterior (es el caso de la Gioconda) o varias (la elaboración original de las escenas de La història de Nastagio degli Onesti y la reelaboración de un copista); pero las presenta contextualizadas como objeto de aprecio e implícitamente se hace mención al proceso de recepción estética de los espectadores.

Los museos se tratan en otras obras de este periodo de forma ambigua. Se pintan de manera detallista, resaltando las singularidades de sus aspectos arquitectónicos como contenedores. Pero también se ponen de manifiesto sus contradicciones: el expolio cultural, la mercantilización y la banalización del arte son tres circunstancias señaladas en varias obras. De alguna forma, Miró pretende prevenirnos de lo que se podría deducir de las apariencias y nos advierte de los condicionamientos que afectan a nuestra experiencia estética o apreciativa.

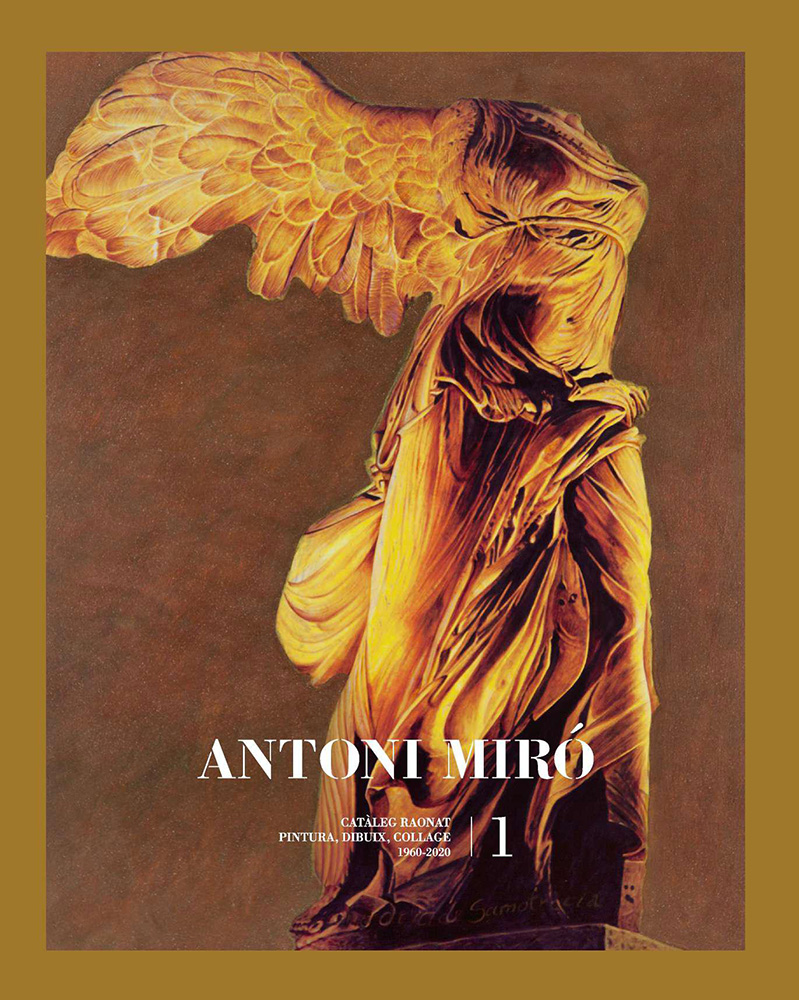

Precisamente, la interacción objeto artístico-espectador es otro asunto que el artista desarrolla teniendo en cuenta cambios de lenguaje. Esculturas de importancia capital como Mano izquierda levantada, de Julio González, o la Victoria de Samotracia son pintadas por Miró. Encontramos en estas acciones ese fondo de insistencia recursiva porque se trata de representaciones de modelos que son, simultáneamente y en origen, representaciones de otras ideas. Aun así, se plantea una sustitución parcial de referencialidad mediante alteraciones que distinguen lo que se pinta de aquello que sirve de fuente de inspiración. El afán emulador de la realidad cede ante el interés de distanciarse de esta aunque no lo parezca a primera vista.

Aludir a la relevancia del pasado es una de las tareas a las que se ha dedicado el artista con más intensidad durante este periodo. Lo ha hecho distinguiendo y homenajeando, además de a muchas obras de arte de importancia crucial, a una amplísima nómina de personas del mundo de la cultura, mayoritariamente pero no exclusivamente del ámbito catalán. La subserie conformada ha sido titulada “Personatges”. Escritores, músicos, científicos, artistas… como por ejemplo los casos de dos buenos amigos de Antoni Miró que ya nos han dejado, los también alcoyanos Ovidi Montllor i Isabel-Clara Simó. Todos retratados en blanco y negro, afectados por una textura que denota el paso del tiempo que los ha sancionado como hombres y mujeres ilustres, constituyen las imágenes de un panteón particular del pintor.

Sin embargo, como es evidente, en el pasado no todo es gloria. Miró considera que la memoria del convulso siglo XX se tiene que preservar. No se deben olvidar sucesos despreciables. El terrible sufrimiento de las víctimas inundó espacios de represión, a pesar de que parece ausente ahora. Por eso pinta Ciutat sense sortida (2005) o L’Estadi Nacional (2004). La aflicción que se podía apreciar en la mirada de un hombre antes de ser fusilado en uno de sus cuadros de la subserie “Dòlar-Xile” ya no está presente explícitamente en esta última obra. En cambio, lo extraño de observar edificios tan grandes como estos, que acogen generalmente a multitudes, totalmente vacíos, puede conducir al recuerdo de las injusticias que se han perpetrado.

Estos escenarios deshabitados contrastan con los de las numerosas manifestaciones que se produjeron después de que la ciudadanía sufriera los estragos de la última crisis económica global. Hubo entonces concentraciones masivas contra los gobiernos que impulsaban medidas de contención presupuestaria en Europa. Junto con estas, resurgieron visiones reivindicativas y liberadoras. Este tono contestatario, de denuncia de injusticias sistematizadas, también se produjo en los países árabes. Pero la primavera en la que centraremos nuestro comentario es la valenciana.

Con la subserie “Mani-Festa” (2012-18), el pintor vuelve a hacer crónica de la realidad. Su pintura aspira a ser un vehículo crítico con el que inmortalizar un momento particularmente tenso y a la vez esperanzador. Con la obra Prohibit pensar (2012) hace ver la revuelta incipiente contra el gobierno valenciano de entonces. Si en los setenta los personajes se presentaban ante un fondo neutro con cierto grado de realismo, ahora Miró los destaca con todo lujo de detalles sobre el resto de la imagen, que queda amortiguada.

El núcleo de interés son determinados procesos de acción y de reacción que se mantienen entre los manifestantes y la policía. En la obra Primavera valenciana (2012), una joven se defiende y trata de huir de dos agentes; en Policia a València (2013), un joven ya está neutralizado. La intención del artista es subrayar estas circunstancias concretas dentro del gran disturbio. Utiliza diversos recursos plásticos para aislar y destacar las figuras involucradas y también para indicar direcciones de movimiento. Aun así, la voluntad de trasladar al espectador la realidad con toda su dureza lo lleva a evitar transformaciones que puedan desvirtuarla.

La última de las series desarrolladas por ahora se denomina “Sense Sèrie”. Realizada desde 2013, el pintor modula su propio tono reivindicativo acercándolo al extremo valorativo. El reconocimiento a su ciudad es fundamental. Persigue significar determinados elementos valiosos de esta ciudad industrial como, por ejemplo, los puentes con los que ha ido venciendo los límites orográficos que constreñían su crecimiento. Pero también destaca que durante la Guerra Civil la solidaridad internacional permitió que se instalara un hospital sueconoruego.

Así, dentro de la subserie “Costeres i Ponts” encontramos vistas urbanas centradas en estos últimos artefactos. Sus estructuras quedan muy definidas gracias al rigor geométrico que les es connatural. Aun así, a causa de la arbitrariedad de la disposición de otros elementos que las rodean, resulta que la pulcritud se ve corrompida. Sabemos que esta contradicción ha sido a menudo la base de la credibilidad de las representaciones pictóricas de carácter realista, puesto que la perfección absoluta disuelve las posibilidades de verosimilitud.

Pero no solo refleja aspectos alcoyanos. Los trabajos dedicados al Tribunal de las Aguas suponen principalmente la valoración de esta institución valenciana consuetudinaria, pero también del marco que acoge a sus miembros y de todo el sistema de riego que articula el campo. Destaca las señeras que hay en la Puerta de los Apóstoles de la catedral de València como rasgos identitarios y las reproduce separadas y teñidas de varios colores. Aun así, además, pinta con el mismo grado de detalle aparatos hidráulicos puramente funcionales, como una llave de compuerta que regula el caudal de una acequia.

Los últimos dos años, Miró ha incidido en parte de su producción en el erotismo y la sexualidad, y ha constituido una subserie denominada “Nus i Nues”. Como indica el título, ya no son solo foco de atención la sensualidad y la belleza femeninas, sino también las masculinas. De forma explícita, se representan cuerpos enteros o fragmentos de estos, y esta desnudez se muestra sin ocultar, además, una actitud lujuriosa.

Es, pues, importante el cuerpo, o una parte, como sustrato del deseo, factor puramente mental. Así, pinta meticulosamente los cuerpos y, a menudo, incorpora rasgos que forman parte de su repertorio identitario para reforzar el vínculo que establece. Más allá de la controversia, en el fondo se trata de ejercitar la pintura mediante el recurso al modelo desnudo.

Comentarios en torno a cuatro ámbitos de interés

Después de haber comentado hasta este punto las series con las que el artista ha estructurado su trayectoria, procede, como se señalaba al comienzo, evidenciar las cuatro áreas de interés que las vertebran transversalmente. La primera y más general está relacionada con su consideración personal distintiva hacia la pintura como disciplina cuyas capacidades incluyen comprender la realidad del mundo y vincularse personalmente con su mejora. De las otras tres, dos son propia y casi exclusivamente temáticas: memoria e identidad, por un lado, y erotismo y vida, por otro. La última no es, no obstante, única y fundamentalmente argumental. La condición de denuncia y el carácter político que son consustanciales a su producción salen de los límites del espacio de los contenidos, y son verdaderamente los cimientos de su visión crítica. Porque está claro que a lo que Miró aspira en última instancia es a que su pintura sea un dispositivo transformador de la sociedad contemporánea.

A pesar de tratarse de cuatro ámbitos de atención recurrente durante su carrera pictórica, su incidencia en cada una de las series se va modulando y no se presenta siempre en el mismo grado de intensidad. El suyo es un programa estético, en definitiva, que admite el recurso continuado a este abanico de intereses de manera diversa y con niveles de implicación también diferentes.

La pintura de Miró, como Román de la Calle señaló tan acertadamente, es de concienciación; pero, además, como explica este teórico, hay un grado destacado de concienciación de la pintura en cuanto a la construcción de su lenguaje plástico. Es decir, coexisten una predisposición a orientar las reflexiones del espectador y otra dirigida a interiorizar los efectos sucesivos de sus creaciones en las nuevas composiciones, dentro de un mecanismo de autoaprendizaje continuo y cada vez más sofisticado.

La pintura en este caso sirve primariamente como un canal de comunicación con quien observa la obra, pero simultáneamente es también no solo una vía de aprendizaje, sino de relación con el mundo. Hacer crónica de la realidad contemporánea denunciando graves injusticias o cuestionando determinadas circunstancias improcedentes es un doble proceso mediante el cual, por un lado, se revelan situaciones que hay que combatir y, por otro, se demuestra el compromiso solidario del artista. Como hizo Zola en relación con el caso Dreyfus, Miró acusa públicamente. Se ha pronunciado ante la sociedad, pintando contra los que ha considerado los poderes opresores en cada momento.

Este era un posicionamiento generalizado en los setenta; de hecho, ya dijo Mario de Micheli sobre las obras de los integrantes del Gruppo Denunzia, del cual formó parte Miró, que las suyas eran “imágenes contra e imágenes por: contra la ofensa a la integridad del hombre y por la afirmación de su libertad”. De hecho, la gran mayoría de las obras de Antoni Miró de las series “Amèrica Negra” (1972), “L’Home Avui” (1972-74) y “El Dòlar” (1973-80) se sustancian expresamente en esta dualidad que consiste en actuar contra los agentes opresores y, al mismo tiempo, clamar por la libertad de los oprimidos.

Igualmente pasa con muchos de los trabajos de las últimas series ya en este siglo, en los que se explicita la posición de denuncia. También, en los ochenta y noventa, en “Pinteu Pintura” (1980-91) y “Vivace” (1991-2001) se apreciaba esta crítica de carácter ciertamente político. Aun así, en estas dos series la ironía y la estetización hacían que su manifestación fuera menos directa que en los setenta.

Dos son las corrientes pictóricas decimonónicas que se pueden vincular al realismo social del siglo posterior al que nos referimos: el realismo propuesto por Courbet y la pintura de historia, que, por cierto, cultiva tan brillantemente el alcoyano Gisbert. Aun así, si bien es cierto que la obra de Miró como arte crítico realista se ocupa de los simples mortales —como diría Proudhon que tenía que ser en Du principe de l’art et de sa destination sociale, inmejorable alegato a favor de Courbet—, la suya, más que pintura de historia, ha sido de historias.

Aparte de articular con la pintura un medio denunciador de agravios de carácter fuertemente político, esta ha constituido también en numerosas ocasiones a lo largo de la trayectoria de Miró el objeto o tema de reflexión mismo. La recursividad que informa la serie “Pinteu Pintura” (1980-91) es el ejemplo más claro. “Imágenes de las imágenes”, así calificó adecuadamente Román de la Calle estas creaciones basadas en la combinación de elementos del repertorio canónico. Esta referencia a la metapintura, la hizo resiguiendo y adaptando planteamientos de filósofos relevantes como por ejemplo Husserl o Benjamin. En el caso de Miró, formular nuevos mensajes a partir de fragmentos, signos y símbolos ya incorporados a la tradición de la pintura occidental responde a una estrategia ambigua. Está amparada en la valoración y el reconocimiento de la historia del arte, pero, en algunos casos, otorga una capacidad crítica que subvierte los sentidos originales.

Esta dislocación semántica que procede de la yuxtaposición de fragmentos de imágenes que carecen de relación que los conecte es la estrategia fundamental de los collages. Los de Renau son un claro referente para Miró, como demuestra la coherencia entre estrategias compositivas y la intencionalidad crítica. El artista, al inicio de cada una de estas operaciones, selecciona varios elementos que, a pesar de poseer una carga significativa determinada, aislados abren nuevas vías interpretativas respecto de sí mismos cuando se ponen junto a otros. La controversia resulta de una asimilación desproblematizada en primera instancia. La familiaridad se vuelve extrañeza, pero esta, a diferencia de los precedentes surrealistas, debe llevar al espectador al campo de la consideración crítica y animar sus acciones políticas.

Ya se ha dicho que la obra de Miró comparte el uso intenso de la intertextualidad con los representantes del pop crítico valenciano. La suya es, como también la de ellos, una crítica ácida e irónica generalmente; aun así, a veces esta mordacidad se sustituye por un cierto lirismo, sobre todo en las series “Pinteu Pintura” (1980-91) y “Vivace” (1991-2001).

Explicadas las funciones particulares que desarrolla la pintura como vehículo crítico y fuente referencial, hay que aproximarse ahora a los tres ámbitos temáticos señalados como áreas de interés constantes: memoria e identidad; erotismo y vida, y denuncia y política.

Con carácter diverso y más o menos intensidad, las tres se pueden apreciar en las varias series. Pertenecen a lo que denominamos la memoria y la identidad los referentes y las reflexiones que involucran aspectos culturales o que le son muy próximos. El entorno próximo del artista presenta dos caras: en el plano material podría ser el territorio en el que habita el artista, por ejemplo, y en el plano espiritual, los poetas que conoce y venera, entre otros. Está claro que la cultura que siente como propia, la catalana, es el aspecto en el que incide más frecuentemente. Pero también hay otros referentes ajenos a esta con los que crea relaciones y a quienes rinde homenaje.

Un testigo de la transversalidad del interés por esta clase de factores de carácter se evidencia mediante el recurso a la representación de la señera. La primera obra capital en la que se alude a la cuestión de la identidad es, sin duda, Llances imperials (1977). Sin embargo, durante la década siguiente varias de las obras de la serie “Pinteu Pintura” (1980-91), como es el caso de Temps d’un poble (1988-89), la emplean como motivo central de la composición. Pero, quizás, la obra en la que más importancia adquiere el símbolo sea Senyora Senyera (1987), que nos remite inevitablemente a uno de los iconos pintados por Delacroix. Esta nueva libertad, en cambio, no blande la bandera en su guía popular, sino que se rodea con esta manteniendo los pechos descubiertos, haciendo señal de identificación íntima. Mucho más tarde, Miró actúa de nuevo de forma parecida en la obra Senyera (2012), manteniendo la enseña como un motivo de orgullo que protege la desnudez de un cuerpo femenino. En otras ocasiones no fue así: Altre amar (1999) y Tornarà al sud (1999) son dos pequeñas tablas que muestran mujeres completamente desnudas sosteniendo los palos de unas señeras que ondean al viento.

El paisaje que reconoce como propio —por un lado el de la ciudad de Alcoy y el de las montañas que lo rodean, y por otro el de la costa mediterránea— es otro punto referencial notorio en clave identitaria. Terminó algunas obras durante la primera etapa, que denominamos “Opera Prima”, sobre Alcoy. Y, sobre todo, será la reciente “Costeres i Ponts” donde se aglutinan numerosas representaciones de distintos lugares característicos e infraestructuras de paso de esta ciudad industrial. Además del escenario urbano alcoyano, en las obras de la serie “Vivace” (1991-2001) demuestra la vinculación con los parques naturales que rodean la ciudad y también con el litoral mediterráneo; unos sometidos a los efectos contaminadores antrópicos, y el otro asediado por el desarrollo de los procesos de urbanización desde los sesenta.

El pintor se reconoce también en los otros y ha utilizado la pintura para relacionarse con los que tiene o quiere tener cerca. Algunos miembros de su familia y amigos o amigas de infancia y primera juventud fueron objeto de sus primeros retratos. Compañeros de etapas posteriores, como por ejemplo Ovidi Montllor, Isabel-Clara Simó, Antoni Gades… se incorporan también como retratados a la larga nómina de personajes que admira y conforma la subserie “Personatges”. Dentro de esta lista encontramos a Freud y a Marx, como origen de los cuestionamientos críticos contemporáneos, o a Fuster, como iniciador de un proceso de reconocimiento de lo que significa ser valencianos. También a muchos escritores y poetas: Miguel Hernández y García Lorca, en lengua castellana; Pla o Espriu, en catalana. Músicos como Pau Casals, cantantes como Raimon. Y, por supuesto, pintores, como Dalí o Tàpies.

Precisamente, muchos elementos de las obras de estos dos artistas, como también de Picasso y otros muchos anteriores desde el siglo Xvi, se incorporan a los cuadros de Miró que forman la serie “Pinteu Pintura” (1980-91). Esta forma de actuar le permite interiorizar las claves de sus referentes artísticos y, simultáneamente, reformular el sentido con el que trata de presentarlas nuevamente. Ancla así su producción a la tradición pictórica más valiosa y une identidad y memoria.

Pero no todas las referencias se producen en sentido positivo. Si bien las obras de arte son objeto de reconocimiento, no son pocas las críticas que se dirigen hacia las instituciones museísticas. A propósito, determinados desastres históricos, como por ejemplo el holocausto judío, son representados para que no los borremos de nuestra memoria. También, a menudo, el pintor recurre a determinados símbolos como naipes numerados con el 1707, año de la derrota de Almansa, para destacar negativamente el centralismo español.

Por otro lado, la subserie “Mani-Festa” aspira a formar un depósito informacional que permita reconocer la intensidad de las diversas primaveras en un futuro. Este funciona como herramienta de memoria histórica, gracias a la mirada de la cual quedan a la vista a la vez y más adelante tanto los rasgos positivos de estos procesos como los negativos.

El segundo de los tres ámbitos señalados es el que corresponde al erotismo y la vida. El origen de esta voluntad representacional se muestra en los apuntes, en forma de breves dibujos de línea de lápiz o tinta, con los que retrata al natural jóvenes compañeras desnudas. Es muy característica de estos esbozos la sinuosidad de las líneas continuas con que se constituyen. Son muchas veces dibujos de escorzo gráciles en los que la sencillez y la elementalidad se conjugan y ofrecen estampas que atrapan inmediatamente.

Las primeras pinturas relacionadas expresamente con el deseo y la belleza del cuerpo femenino se encuentran en la serie “El Dòlar” (1973-80). El tríptico The Maja-Today (1975) es una buena muestra, con la cual Miró persigue actualizar sarcásticamente el modelo de Goya. El militarismo y el capitalismo ocupan el trasfondo de esta aproximación lasciva a la mujer, dentro de la cual se incluye una crítica a la prostitución.

Más tarde, en la serie “Vivace” (1991-2001) se recupera esta dedicación al atractivo femenino. La sensualidad de las caribeñas y de las mujeres mediterráneas se celebra casi siempre ante un fondo azul intenso, como si el mar y el cielo fueran los únicos marcos dentro de los que se pueden exhibir. Así ocurre en Benvolença (1999) y Tros de Cuba (1999). También es el índigo el color de la superficie en la que se dispone la figura en la obra Senyera (2012), de una fase creativa muy posterior, la subserie “Mani-Festa”.

No es de extrañar que aisle las siluetas y las disponga sobre un mar o un cielo figurados. De hecho, la naturaleza y la feminidad se identifican o asocian en muchas ocasiones en las obras de Miró. El cuadro Zebres a trossos (1998) es un ejemplo metafórico de esta clase de relaciones.

La explicitación de la sexualidad mediante el dibujo y la pintura de figuras desnudas ha sido, pues, una constante a lo largo de su carrera. De hecho, buena parte de los trabajos recientes lindan con el carácter pornográfico, de forma que siguen el camino iniciado por Courbet con El origen del mundo. Con estas pinturas obscenas, el pintor no rehúye la incomodidad que pueda generar en el espectador: intenta desafiarlo. Mayoritariamente, el pintor representa mujeres en situaciones explícitamente sexuales, pero también hace lo mismo con hombres. A veces, incorpora tatuajes de manera fetichista sobre los cuerpos con fines intensificadores.

Como indica el nombre, la vida, junto con la sensualidad, es el motivo principal de la serie “Vivace” (1991-2001). Se evidencia toda su potencia en varias ocasiones. Pero también se remarca a menudo su carácter frágil. Esto último se consigue por el hecho de solo remitir a ella, sin representarla, advirtiendo de las amenazas. La obra Parc natural (1993) es probablemente el ejemplo más claro de este mecanismo de concienciación de los riesgos. Otros cuadros anteriores —como Intrús a Cofrents (1989), de la serie anterior, “Pinteu Pintura” (1980-91)— actúan en la misma dirección.

Esta tarea de sensibilización que responde a la vocación del pintor de erigirse en un intelectual influyente en la sociedad que lo acoge conecta con el tercer eje de contenidos, el que corresponde a denuncia y política. Y es que su pintura nunca ha estado al margen de la acción crítica. Su planteamiento desde el principio ha consistido en hacer que sus reflexiones sobre el presente vayan dirigidas a despertar conciencias, tal como demuestra la obra inicial El bevedor (1960).

Específicamente, sus primeros análisis políticos se produjeron sobre la Guerra de Vietnam a finales de los sesenta. Después, llegaron la pobreza y la violencia que sufrían los negros en los EE. UU. a finales de los años sesenta y principios de los setenta. El racismo abrió paso a la reflexión sobre el neoliberalismo, el imperialismo yanqui y la militarización, y también a la defensa de los intereses de los pueblos oprimidos en todo el mundo. La suya era fundamentalmente una crónica de la realidad geopolítica global de entonces.

A finales de los setenta y sobre todo durante toda la década de los ochenta, la posición crítica afectaba a otras cuestiones que eran más próximas. Es decir, la Guerra Civil (Personatge esguardant Gernika, 1985), los primeros resultados de la transición a la democracia en el Estado español (Díptic democràtic, 1986-87; El misteri republicà, 1988), la identidad nacional valenciana (Llances imperials, 1977), el centralismo españolista (Retrat eqüestre, 1982-84) o las políticas de izquierdas (Qui té por, 1988).

En los noventa, la denuncia se dedicaba a la depredación del medio ambiente. La contaminación creciente derivada del consumismo y sus efectos devastadores sobre el territorio son las dos consecuencias del neoliberalismo sobre las que centró sus esfuerzos críticos.

Con la irrupción del siglo XXi, el pintor reorientó nuevamente su atención hacia los agravios de carácter político. Durante el primer decenio, además, recuperó el nivel mundial; no fue así en el segundo. El atentado del 11-S o las guerras de Irak o Afganistán fueron parte de las ocupaciones en el primero, mientras que en el siguiente los graves efectos de la crisis económica se evalúan dentro del ámbito español y las revueltas ciudadanas dentro del valenciano.

Interpretados estos tres amplios conjuntos temáticos que las obras pictóricas de Antoni Miró reflejan constantemente, aunque de manera muy diversa, hay que finalizar este relato taxonómico, cuya parte central está conformada por una secuencia de referencias sucintas a cada una de las series que ha desarrollado el artista a lo largo de su carrera, indicando cuáles son sus características generales.