«El vol del gat»: the infinite pathways of art

Carles Cortés

We would have to ask the writer, academic and politician Abel Prieto (born in Pinar del Río, Cuba, in 1950) whether he had ever sensed that one day, the painter Antoni Miró (born in Alcoi, Spain in 1944) and the ballerina-choreographer Sol Picó (born in Alcoi, 1967) would be somehow linked to his literature. We would need to know if he had ever sensed that as a result of those Caribbean nights when writer’s ink started to appear on blank pages and chapters were beginning to take shape, the result would one day blossom as the union of both the painter’s and the choreographer’s creativity in such a way as to become a single, distinct work that is both multifaceted and complex; we wonder if he had ever foreseen a work that embraces literature, painting and dance in the same space and which enthrals and traps the reader-spectator in a quite intimate and select celebration.

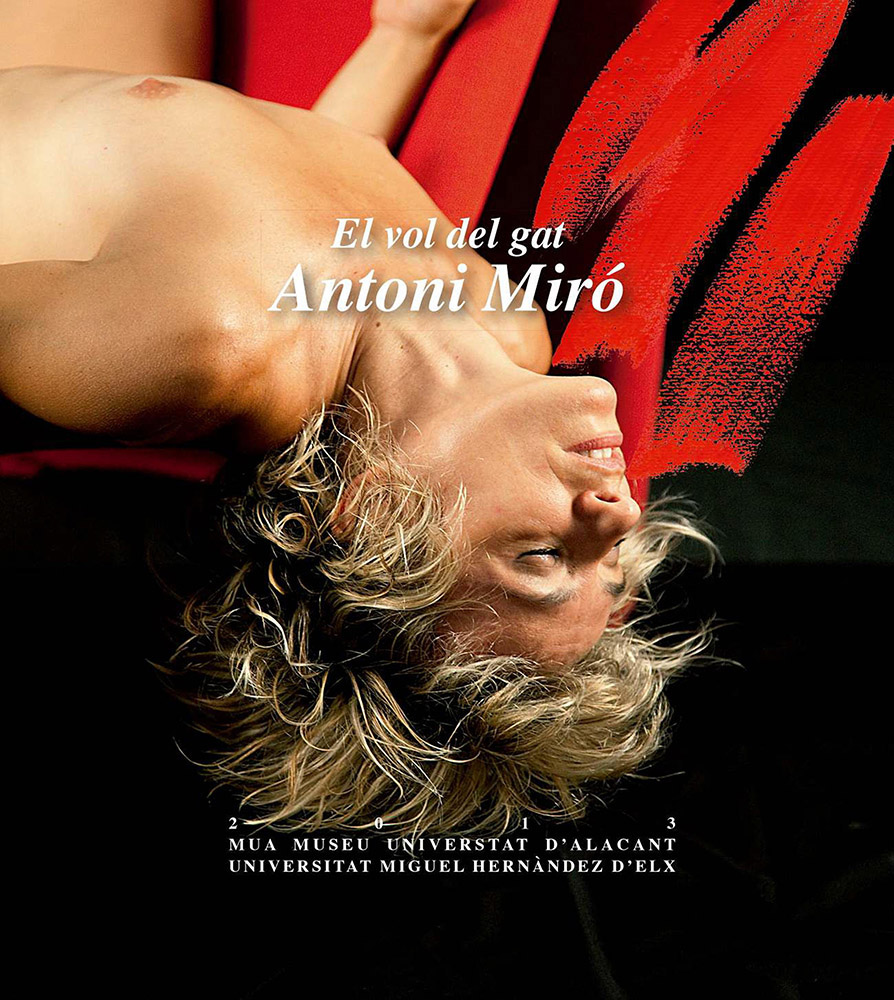

What is apparent is that Abel Prieto’s novel El vuelo del gato (La Habana, 1999) translated into Catalan as El vol del gat (2012) has embraced two quite distinct discourses that are nonetheless extremely complementary. We thus have twenty-seven chapter titles that confer names to the same number of works that captivate the reader thanks to the inspiration drawn from a work that is complex, emotive and sensual; the creative fruition of three artists committed to art. With the paintings by Antoni Miró serving as a starting point, the readers of Prieto’s novel will link the exploits of the boys Freddy Mamoncillo and Marco Aurelio to the naked bodily presence of Sol Picó. However, the same landscapes as in the novel, framed within chromatic Cuban realism and intense descriptive imagery by Prieto, are not to be found. El vol del gat has been recast as a pictorial series where intense colours such as red, black and blue become part of the moving tapestry executed by the choreographer. We are presented with ever-changing chromatic pathways that seem to caress the dancer as she presides over this pictorial assembly and yet she finds herself trapped by this imagery. As a result, the reader and the spectator are surprised by this union of discourses that reveals that the lives of Marco Aurelio and the rest of the Cuban writer’s characters are indeed linked; these lives start on the black and white plane of the pages of the novel and are transfigured at quite another level by Sol Picó’s more seductive and commanding dance movements. In her interpretation, Miró’s key assistant makes the miracle a reality. She skilfully entwines the dynamics of the stories in the novel with her choreographic performance.

It is not surprising that we can detect, in this meeting of two artists that mutually draw inspiration from Abel Prieto’s work, that each figure assumes the role and approach of the two main characters. At the beginning of the novel we have the enactment of a basketball match with teenage players. Marco Aurelio is portrayed, in the words of the writer as “moving ahead without any ostentation, free of undue excitement, in his own restrained, yet comfortable style of dribble (moderation per se)”, like a Miró with the ball: a strong, secure yet discrete character like the painter from Alcoi. But bursting onto the scene we have Freddy Mamoncillo (a kind of advance introduction of Sol Picó in Miró’s imagery) who is portrayed with «a rapid rippling of textures, muscles, that swing his t-shirt from side to side and those wide, loose, crazy, shorts”. It is not hard to imagine the faces of the painter and the dancer in this scene as they strive to give every ounce of themselves in a bid to capture and reflect the characters initially conceived and created by Prieto with ink on paper. And we can imagine their faces at the end of the chapter, where the setting and events will linger on with the reader (and the characters) on every page of the book:

«I can reconstruct the culminating moment of the match, this time captured in an imaginary frieze: Here we have our Marco Aurelio, a Pre man; he has just stepped discretely aside after passing the ball [Toni and his work] to Mamoncillo and now he has shrunk to a smallish figure, motionless yet alert, almost a medieval icon and we can just make out from his pensive gaze that - ah!, the ball finally goes in! - he is on a journey of introspection starting at the middle of a game somewhere and withdrawing to another game within himself, to that place which is the (solitary) abode of the reasonable soul while his body continues here below, physical, on the surface of the frieze, on the basketball court, interacting among the other sweaty bodies».

The character could be understood as the essence of air itself, as if suspended for eternity in his glorious jump (Picó’s pure dance): “that trampoline-like jump that would lead to the downfall of Tamakún and those determined hands frozen as they aim to take the shot”. Let’s proceed step by step however. Before the work per se we have the people involved; it was Miró who crossed the Atlantic to organise this art exhibition and hence we have the rapport between the painter and the dancer. Although both were born in Alcoi, they met in Barcelona during the presentation of another exhibition at the Institut d’Estudis Catalans which explored the mutual visions between Miró and the poet Miquel Martí i Pol. That event took place in 2009 and some months after, the choreographer posed before the painter for a portrait at his Sopalmo property near Ibi. As soon as Miró had read the novel by Abel Prieto (who had given Miró the book himself when he was the Cuban Culture Minister), he sensed the interrelationship “When Sol moves, when she dances, she does so like a cat”, said the artist upon finishing the series. The point is that Picó moves like a cat, as do all of Prieto’s characters, proceeding with subtlety, with flexibility and adopting relativity in movement and relativity in dealing with problems. Through metaphor, they make possible the impossible, in short, a flying cat.

We are now going to speak of the Cuban writer, Abel Prieto whose life and works have always been inextricably linked to his country. He is a writer, editor and university professor and for fifteen years was the Cuban Republic’s Minister of Culture. Since 2012 he has been a presidential advisor at various state and ministerial councils; he is also a specialist in the writer and poet Lezama Lima. Abel Prieto’s literary works include Los bitongos y los guapos (1980), No me falles, Gallego (1983) and Noche de sábado (1989). With his novel El vuelo del gato, he won the Premio de la Crítica in 2001. His latest novel, Viajes de Miguel Luna, was published in February, 2012 and in recognition of his literary achievement, the French Republic bestowed him with the Order of Arts and Letters.

Throughout his life, and from the perspective of the plastic arts worker, Antoni Miró has collaborated in a whole host of initiatives concerning cultural promotion and was connected with the artistic movement led by Equipo Crónica. His friendship with Antonio Gades led to his irst-hand knowledge of the reality of the Cuban people and to the subsequent closeness he feels to them; this rapport is evident in the works presented herein. His personal and artistic development in the 70s is steeped in the ideological and aesthetic trends that shaped the deep social changes in Spain; it was the time of transition from a dictatorship to a democracy and the recovery of individual freedom. His critical appraisal of the period, together with his understanding of the reality of the Cuban people, made him a key figure in the defence of freedom while at the same time being outspoken against the excesses of capitalism. After many exhibitions in Cuba, his appraisal and personal concern for Cuba, led to his official recognition in 2008 by Cuba’s Ministry of Culture in the form of Distinción por la Cultura Nacional; the prize bore witness to his artistic career and to his personal commitment with culture and society. At that time, the director of La Habana’s National Fine Arts Museum, Moraima Clavijo, recognised that Miró was somebody “with exceptional accomplishment, imbued with realism, who transcended the formal mastery of technique and openly championed the causes of social denunciation; a man who understood the subtleties of daily life, its ironies and the contemporary nature of the most immediate realities”.

There are a number of primary protagonists in the presentation of Miró’s works who concern us here. We have the dancer herself offering her own impressions of the moments captured in the portraits, the fraction of a cadence, the instant parenthesis marked by the camera’s diaphragm, indeed, that of the human eye. Picó confirms this when she states, “I can’t recognise myself; I’ve seen myself so many times in videos, moving, but this is the first time I’ve been the subject of a portrait” This is a new challenge for Picó and it provides her with a new perspective on her work and passion as nobody had ever painted a portrait of her. Consequently, she has an opportunity to reflect upon her image outside the context of continuous movement. She has, as we do, a series of fragments of movement that are defined by the title of each chapter in Prieto’s novel. This is the game, the challenge that Miró offers us as observers of the collection of engravings; he also portrays the smile of Cuba in the figure of the dancer from Alcoi. We have before us innate optimism, an active stance for the daily problems as those faced by Prieto’s characters. In the twenty-seven pieces making up the collection, we can trace the parallelism between them, the elegance, the mystery and the sensual movements; all of them scrutinised and perfect. This is where she becomes the lying cat that glides through the novel from cover to cover; the island, Cuba, is her space, while Picó’s own studio was the laboratory for observation and analysis.

Sol Picó and Abel Prieto have still not met. Nonetheless, the choreographer visited the Caribbean island in 1996 to offer a course that she co-taught with Marielena Boan. Both dancers offered students their extensive experience and harmonious corporal work. Many years have passed since Picó left Alcoi to start dance studies in Alacant, Barcelona and Paris. In 1993, she founded Companyia Sol Picó which was the resident dance company between 2002 and 2004 at the Teatre Nacional de Catalunya; productions included Besa’m el cactus, Barbi-Superestar, Paella mixta, Sirena a la planxa and El llac de les mosques. Sol Picó has received several prizes and awards and she is ten-times winner of the MAX prize. The staging of her dance involves an abundance of movement and dynamism but humour also makes a pleasing presence as she narrates the stories that are interlinked. Picó’s approach is imbued with tokens of irony and a subjective vision of reality that dovetails well with the works of Antoni Miró and Abel Prieto. Perhaps we should also mention the humorous links between the works of these living artists.

As for the painter, Miró’s professional career has been prolific in his quest to unite diverse artistic discourses. At the onset of his career in the 60s and 70s and particularly in the 80s, with his “Pinteu pintura” series, Miró has been drawn to discourse fusion concepts, the idea of bringing together the visual and literary arts. In the recent “Mirades creuades” series, he has drawn from his relationship with the poet Miquel Martí i Pol and in “El vent del poble” he reflects on the dance of Antonio Gades and the poetry of Miguel Hernández.

We will find a similar process in the choreography of Sol Picó who perfectly incorporates the tone of the novel El vuelo del gato and becomes part of the stories, part of the novel as she embraces the souls of the characters devised by Prieto. This is a consequence of the personal review by Antoni Miró of his own work and other shared realities. The historian Josep Forcadell pointed this out in an anthology of the painter’s works: “in Toni Miró’s paintings, by using the vigorous seeds of other narratives, a new vision of history is germianted and this will give birth to new surprising understandings that we may have of reality, of restless souls, of often disturbing ones, but always busy growing”. This is what we find in the twenty-seven engravings that focus on Sol Picó and which is incumbent upon Prieto’s novel: the work is more complete, expanded, new points of view are admitted; new characters appear in the firm and smooth gestures of the dancer from Alcoi. As had previously occurred with Gades, Miró has captured the loci of Picó. We only need to refer to his notebook jottings that recorded working with the dancer from Elda in the summer of 1977: “Gades dances for me, he interprets fragments of works he has performed and he speaks to me about them so that I get an understanding what he has done as a dancer.” This is how the painter was able to link the sensuality of scenes with Picó with the vicissitudes of one Freddy Mamoncillo.

We would also need to take into account an element present in the three artists: eroticism. In Prieto’s case, the sensuality of the hot Caribbean countries understood as the carnal and complex-free relations reflected in his novel are also an aspect with which both the painter and dancer feel quite comfortable with; indeed, they have reflected on the erotic in many of their works. Speaking in relation to women and sex, the critic Bujosa affirmed in 2001 that Miró observes them “with a dose of irony, with nostalgia and the distance befitting a man who feels he is no longer young enough for complicated entanglements.” This irony was seen by Manuel Vicent in 1999 as constituting one of the biggest contributions of Miró’s paintings; Vicent writes: “irony is an essentially Mediterranean dialectic instrument, an excipient of the intelligence that lies between the conscience and analysis. Antoni Miró is a master of this mode of communication by offering the observer the gesture of the accomplice that makes the grey matter of the brain break into a smile.”

It is sensuality itself that is the passive trigger of things and notably so in a scene at the end of the novel, a scene we cannot reveal but which confronts the two Cuban archetypes devised by Prieto with the personalities of the two artists from Alcoi. There is significant similarity between the story narrative and reality; we have the two artists looking back at their long careers; their stories and visions are different but the facts are similar. After all this time, the only possible outcome is to bring them together once more perhaps forever. Aurelio-Picó’s stoic stance as fait accompli, (since virtue and reason are not negotiable in the painter’s work) and Mamoncillo-Picó’s reflective, dynamic position, powerful and charged with emotion, join in a final shared, healing and meaningful moment. We would hope that the work of both artists, having germinated from a previous work that has been motivating for them, may be definitively integrated in this volume that takes up three artistic modes (just like those mentioned in the novel) and that the lucky reader will only stand to benefit.

In this work, Abel Prieto and Toni Miró coincide in the vision of a silenced narrator giving a firsthand rendition but who nonetheless anonymously describes scenes in the narrator’s imagination. We have here a privileged observatory of the actions and thoughts of the young characters as they embark upon their lives, enabling us to explore their personal growth; sensations are delved into, from the smells of the streets of Cuba, to the daily ins and outs of the characters in the narration, to the story of a group of friends that had been originally geminated in Prieto’s mind. The characters are represented and framed by Miró and Picó as a metaphor of the struggle of literary characters in search of meaning, of their own identity. We might therefore conclude that Antoni Miró’s works are of a kind that seeks awareness, one that raises consciousness; it is a genre that calls for a reflection on people and their attitudes. But we also need to debate the degree of awareness-seeking since various techniques; experiences and resources are put together in a specific visual discourse. We have here discourse and visual content that pursue relentless ideological cross-communication and yet at the same time, form a blissful aesthetic medium. The stuff of El vol del gat is this: a bridge that connects, a dance step, a balcony to balcony conversation over the streets of La Habana, a moan, somebody weeping, somebody crying out, indeed, all that we may consider intrinsic to the world of the three artists: Miró, Picó and Prieto, the protagonists of this story.

Carles Cortés Orts and Raúl García Sáenz de Urturi