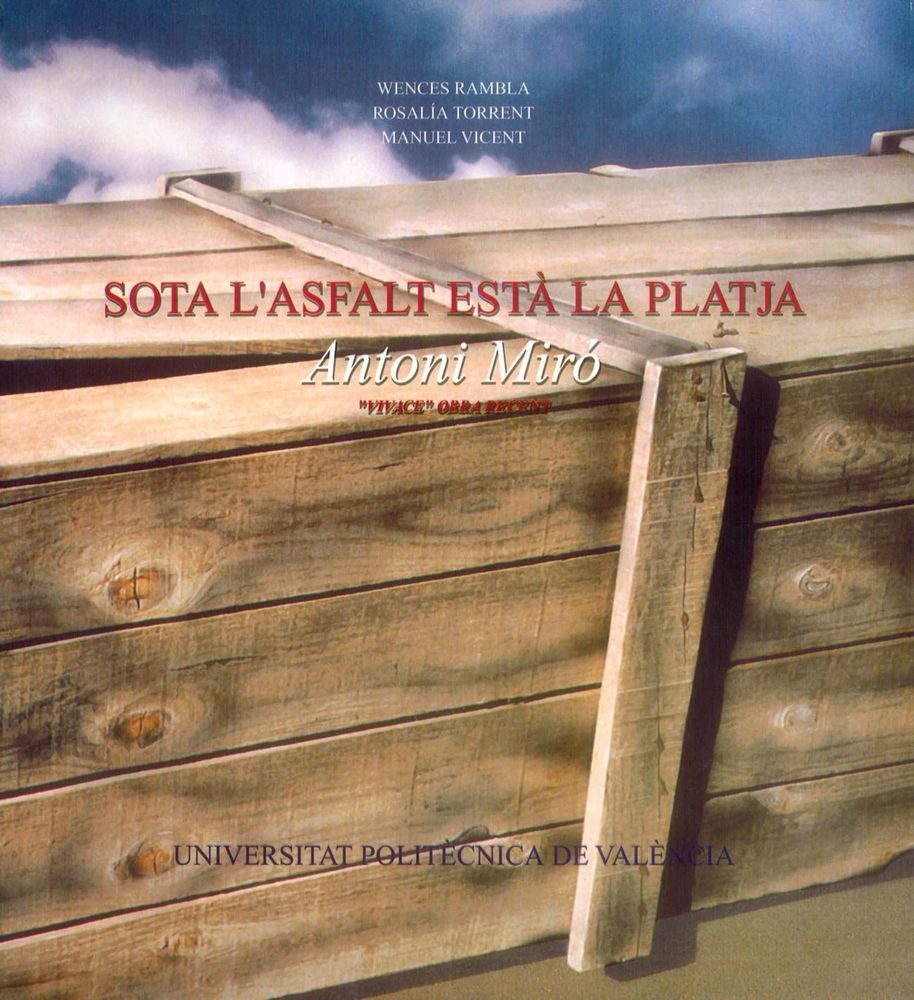

Under the asphalt, the beach

Wences Rambla

What better time of year than summer to write about the beach! What betther way to remind us that bicycles are for summer, as in the title of that lovely film! Though in this case it would not seem to be such a light-hearted subject to write on, since the fact of saying “under the asphalt lies the beach” like the title of the exhibition, changes things and changes them a lot.

It changes them because we are no longer referring - the painter no longer referring - to that lovely light-filled place, but to an area sought after to be split into grid patterns, developed, reparcelled and subject when all is said and done to land speculation. It is indeed fine to have paths and asphalted roads to get from one place to another, but it is also fine - and is simply natural to keep the beaches like the rivers or the woods, in their original state, as these form part of the environment that is not only natural but also, in its earliest configurations, the memory of a people. But man is like that. We insist on developing in a peculiar sense, developing until putting paid to or seriously spoiling everything we touch: our countryside with a high-impact motorway, the course of a brook for some reason or another, dirtying the side of a mountain with countless rubbish dumps until the process is irreversible, or asphalting what cannot be asphalted.

Our degree of commitment, both with our fellow-men and with different natural settings in which we are all in the same boat, leaves a lot of room for improvement. Although indeed if we do carry this out and intervene in nature, we do so (or do we?) in the name of progress and wellbeing. It is the very least we could do. In this respect, going the opposite way, and taking one more step ahead in his Vivace series, painter Antoni Miró presents this exhibition at the Universitat Politècnica de València and at the Centre Ovidi Montllor in Alcoi when the summer has not yet finished and, we hope, will not be doing too soon, if it cannot go on forever, of course - with gentle sand dunes and grassy dunes, green mountain meadows in spring, those restless thrushes that cross our skies, the funny frogs in water tanks and pools, as well of course as saving whales, white sharks and other more sensational aspects if possible. By the way, and with no wish to cause any offence, it is very spectacular to be concerned with this sort of specimens, as well as the glaciers of the South Pole or wherever these are, and ignore the gradual destruction, as if nothing at all were going on, of the most immediate environment. In this field, as in so many other facets of life, stupidity is rife. But anyway, let us return to scrip.

At this stage in the proceedings, when so much has been written about his life and work, it might seem absurd to start to go through Miró’s plastic career, or just another way to get on people’s nerves. But the fact of someone like him, with his personal evolution, sticking to what he believes in - which is not the result of any sort of opportunism, but of a persuasion that has already lasted many years - is praiseworthy indeed. His commitment with the human setting, whether nearby or distant -just go over his earlier series - and with environmental problems - especially since he began the Vivace series almost ten years ago - is part and parcel of his way of seeing, understanding and living life, as this is expressed through his plastic activities, whether these be painting, sculpture or graphic work. This aspect is indeed one from which his general catalogue system has recently been prepared, with the relevant study-cards being published.

In this exhibition Antoni Miró thus presents us, under such a thought-provoking title with a new set of pictures on this broad but at the same time highly specific subject, though on this occasion he takes up this work again after the presentation of his graphic work at the Wifredo Lara Museum in Havana, and other centres on the island. Though in theory going on with the philosophy involved in his most recent hexachromes, this is modified (for not in vain are we looking at new work now) in order for the manual flavour of his artistic work not to lose any of its uniqueness in spite of the methodological process used for this. Our artist thus makes use of selected parts of earlier works which he puts into the computer, where he recombines icon like fragments into a new image. This image, thus composed as a peculiar original master, is transferred to a plotter which puts this on to a piece not of paper but Tyveck or canvas, a support on which Miró then performs his usual strictly pictorial procedure with acrylics, iron filings and other elements stuck to this -exactly the same in fact as he would do on a painting on canvas without these previous steps. We are thus witnessing a further step forward in his continuous plastic research, in which talking about what he wishes to put across does not entail abandoning the painstaking care of his pictorial processes in the slightest. That’s is, whilst offering us further images talking of the death of nature, cunning camouflage for rubbish, of “brilliant” environmental destruction, false liberties, petrodollars and so on, though also of bicycles with incredible forms, of social idols, of suggestive nude women, of intense desires, he gradually construes a panorama, so personally one of his own, in which all these characters, whether animate, inanimate, human or not, interact, taken altogether enormously vital, as symbols of as many other conceptual spheres of social, political, civic or ultimately existential nature. And he does this without discarding, as I said above, his own aesthetics, and also without taking the slightest step back in the leitmotiv of his persistent ideological evolution. An ideological evolution and plastic progression about which we could -to use the words of Walter Benjamin in the nineteen-thirties- say that whilst politics tends towards aesthetic, art must become politicised. But this politicisation must of course be taken in the noble and not the underhand sense of the word, meaning that is should be understood as a gesture of taking a stance against the world’s problems.