Culture & politics. The d’Après in the context of artistic creation. The historical perspective of Antoni Miró.

Romà de la Calle

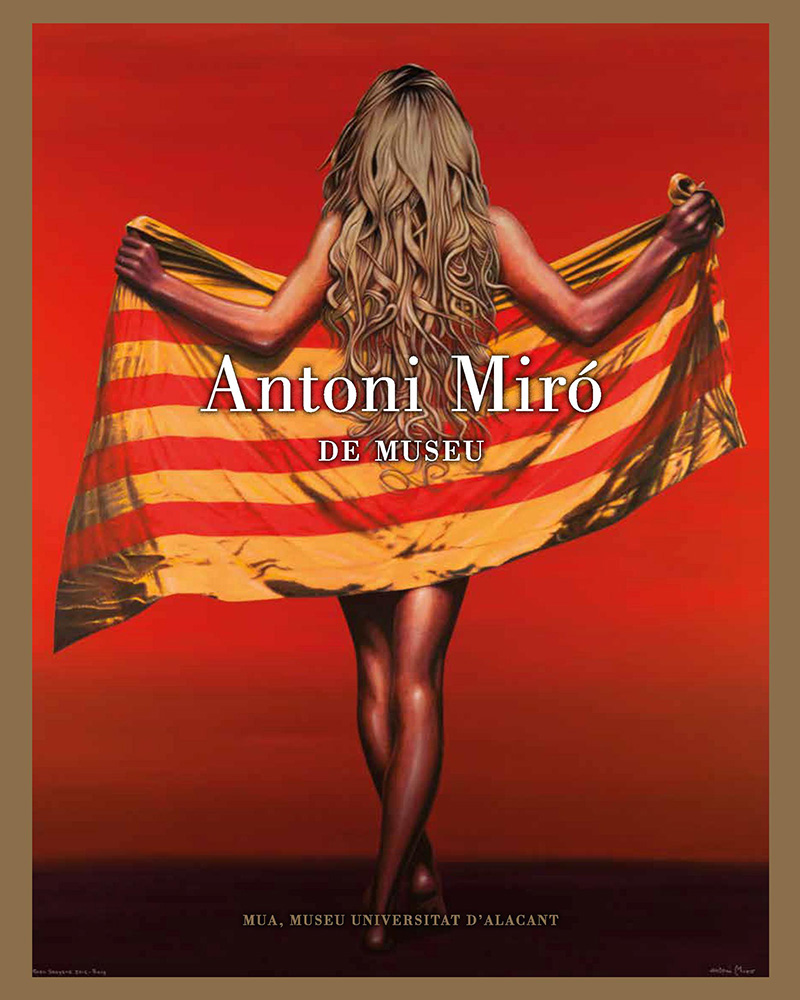

Being invited to intervene in a large-scale solo exhibition based on a selectively retrospective source involves segmenting and focusing – appropriately and ahead of time – the specific space and content, dedicated to the analysis of said participation. And that is how I have organized my (post-confinavirus 2020) collaboration with the MUA, which has lent its generous spaces to this joint historical rereading of certain works / thematic series by Antoni Miró (Alcoi, 1944).

But here, my preference is to speak, contextually, by way of this mild-mannered piece for the exhibition, about a winding and knotted history, based on both the sociocultural action and the subsequent, partisan political reaction. A history whose strategic roots can be traced by following the trail of a specific sculpture – located, in one of its versions, on the campus of the University of Alacant itself. The title of this work is Almansa 1707-2010.

In this striking piece, made from Corten steel (2’90 x 10 x 1’20 m), the patterned treatment of the metal plate, with its studied perforations, becomes – in parallel – a careful historical drawing, with strong narrative references, integrated into the collective memory, precisely on the occasion of the 303 years that had elapsed since the battle, to which the figurative argument of the piece makes an immediate descriptive point.

De ponent, ni vent ni gent (From the west, neither wind, nor people). Ascetically, it is reminiscent of the pithy Valencian proverb, freighted as it is with versatile and eloquent hermeneutics. This sculptural work by Miró is based directly on the rereading and timely extrapolation of a broad tradition, based on war, while assuming, in order to do so, the strategy of the next. That is to say, reinforcing the gaze, from relevant scenes of forced surrenders and strategic groupings of troops…, which already in his celebratory painting, A. Miró had previously been profitable, attracted perhaps by his powerful scenography and, at the same time, emblematic. The direct reference to Almansa 1707-2010 is, no more and no less, the pictorial work of Ricard Balaca (1844, Lisbon-Aravaca, 1882), made in 1862, oil on canvas 140 x 230 cms), and which is deposited, with the title The Battle of Almansa in the Congress of Deputies, in Madrid.

Miró's sculpture is located beside / integrated with a pond in the campus gardens, a secluded and tranquil spot that, often in my visits to the university, I have consciously sought out and strolled around, camera at the ready, exploring and documenting. The raised sculpture park, which has grown up over years, should not, I believe, be considered finished by any stretch of the imagination. This is my appeal to university leaders: that they remain receptive to the patrimonial enrichment provided by open-air art interventions – a feature that is so genuinely characteristic of this university which has just celebrated its 40 years of existence, and which also boasts among its treasures an extraordinary Museum of Contemporary Art, active and innovative, with which the university jointly manages its vital sociocultural policy.

But now, following on from the effective and significant reference to the aforementioned sculpture on campus, I believe it is time to pivot provocatively to another geographic project, by the same artist but completed somewhat earlier, which – with identical historical motivation and even greater ambition and constructive scope – Inspired, in this case, in the direct tradition of Velasquez, specifically in the rereading of the Surrender of Breda or the so-called, by custom, Table of Spears was proposed as a way of occupying/celebratorily presiding over what is perhaps one of the most emblematic entrances to the city of Gandia, the Serralta roundabout. The purpose of the monumental sculpture was also to commemorate the 300 years since that historic date, which provided the title of the piece: 25 April 1707. The sculpture would even go on to give a new name to the roundabout itself.

The inauguration of the sculpture took place, as had been planned, in 2007, when socialist José Manuel Orengo was mayor of the city. The sculpture is of an impressive size – 26 metres long – and weighs 30 tons. It was positioned in a wide space, surrounded by grass, and solidly anchored to the base. The management and installation of the sculpture on the roundabout was carried out through a temporary consortium, and financed by the Ministry for Development. A collective volume documenting the project was published to mark the event. With its long list of interdisciplinary collaborators, this book became the best bibliographic reference to the sculpture and to its historical and contemporary context.

It is sadly well-known that, seven years later, under the municipal mandate of PP politician Arturo Torró, the aforementioned sculptural work by Antoni Miró was taken from the place it had always been intended for, and moved to the Parc del País Valencià, at the far south-eastern edge of the city, and fixed to a concrete platform with nothing in the way of panoramic perspectives around it. From being in a place that was wide and accessible, it was moved to an out-of-the-way corner, totally against the wishes of Antoni Miró and to the detriment of his moral rights as author. The work soon began to show signs of vandalism, and was left there and forgotten about, in forced seclusion. It should also be noted that, from the very beginning, the artist’s complaints and legal struggles were supported by numerous citizens and cultural groups. In the meantime, another, more sanitised, sculpture was immediately commissioned and erected for the northern roundabout of Gandia.

Nor did the repeated appeals and entreaties for the sculpture to be put back on the roundabout meet with legal acknowledgement or support, even when politicians of a different hue and ideological bent came to power in the Gandia city council.

An unfortunate event then, prolonged over time, in which the always-fraught relationship between culture and politics plays its part once again. Culture and politics are two contexts which, by all logic, should need each other, but between which we often see conflict; with culture being politicised in terms of its possibilities of development, and cases of intermittent biases towards the justifying aestheticizing of political action.

Hence, at precisely this juncture, coinciding with the great artistic exhibition of Antoni Miró at the MUA, it seems important to remember – here and now – the links between these works, both of which undoubtedly stem from the same series of proposals and motivations. In doing so, we are obliged to rethink the seemingly-just claim that the author of a work must always have and retain control over his or her productions and projects, and even over the ideas attached to these creative works, including interpretative rereadings and reinterpretations.

Specifically, I have decided to reprint, as part of this commemorative work, the document-report that, in October 2013, I wrote at the request of lawyer and friend, Joan Llinares, attorney for the defence in the lawsuit concerning Miró’s sculpture, and which was presented at the trial. For me it is, without a doubt, a way of implicitly reliving those events, which, of course, have a great deal to do with the career of the artist under discussion.

Creating implies, of course, defending a work, testifying in its favour, believing in it and arguing for its internal codes, if applicable. And that is precisely what my text, written back then – in those historical circumstances – proposed to do with meticulousness and commitment. Today, at this moment of symbolic recovery, loaded with intention and faced with potential readers (and no longer in front of a judge), we are reminded of the aesthetic and functional codes of a sculptural project which became, in effect, a monumental sculpture and which serve as a reminder of a part of our history, and of a forced and controversial cultural policy, whose effects we have borne witness to.

Report on the work of Antoni Miró, titled “25 d’abril 1707”, located in Gandia, on the Serralta roundabout

“The installation of a work of art in the public space is no simple thing; it is a highly complex process, freighted with multiple responsibilities. It implies the plural existence of a close transdisciplinary correlation – within the project itself – between the realisation of the artwork, carried out ad hoc, the artist’s primary creative intention, the spatial context that directly welcomes and empowers the piece, the history that effectively/affectively sustains the citizen’s interpretation and aesthetic experience of the piece, and the socio-political invitation that commissions, supports and enables the work in the first place.

That is, in fact, the great difference between works located in strictly private settings and those that are placed – as a form of challenge – in a public space. In both cases, we can apply the title “works of art” to their respective and specific contributions, their aesthetic power, the solvency of their adequate realisation, the richness of their meanings and symbols, and the committed values, which are recognised and assigned. But to this set of requirements we must add the complex interrelationships that demonstrate and ensure the resonance, impact and consistency of the artworks in the shared public sphere.

In the case of this public sculpture by artist Antoni Miró (Alcoi, 1944), the work’s conception, realisation, installation and spatial conditioning in the northern entrance to the city of Gandia, its well-studied perspectives of the landscape, pointing towards the bell tower of La Seu, give it a remarkable scenographic force. It achieves this impact thanks to its impressive monumentality as well as its commanding and sweeping visual presence in the landscape around it. In addition to the above, it is worth noting the sculpture’s wide range of associated historical references, as well as the inalienable symbolism and rotundity of implementation of its calculated perforations on the 2.5 cm-thick Corten iron plates – with more than 12,000 incisions, which, in the distance, simulate drawings in the style of calligraphic references, offering the traveller a solemn frieze of striking historical continuity. At first the driver glimpses the sculpture from a distance, but the work’s resounding solidity becomes increasingly clear as the vehicle approaches the roundabout. And it is precisely this encounter with an artistic proposal for shared commemoration – in a public space in the city – that will instil in the traveller a desire to learn more, and in greater detail, about the content and aesthetic merits of the piece.

From a vehicle approaching and then circulating the wide roundabout (45 metres in diameter), the citizen takes in the magnificence and massiveness of the work, the powerful perspective and simplicity of forms in their totality, together with the weaving (between static and dynamic) of the many figures in movement, their weapons held up in the air – a reference to the historical surrender that took place at Almansa. The citizen fuses that which he or she contemplates aesthetically, with what he or she knows or remembers from cultural education.

Frieze and colours, sensations in movement, format, integration of profiles, drawings minimized and transformed into games of emptiness, placement and divination of figures, powerful lateral dihedral and horizontal reinforcements of the composition; taken together, these features enable the mobile experience of coming face to face with this artwork. An experience which is transmuted, in turn, into communicative efficacy and powerful historical commemoration. In short, the intervention is fully integrated into the urban landscape, thus orientating the visitor in his or her gradual movement towards the centre of the city.

From our perspective as experts, we detect within the piece the values required and co-involved in its double-faceted nature: it is both a commissioned work of art and a calculated public and urban intervention. These are parameters that, in this case – due to the fact that the piece was specifically conceived of and created for this location – become inseparably tied together. Furthermore, it is important to note that while the subject of the sculpture in question – taken from the collections of Velazquez iconography – has been used in different ways by the same author, this does not make the piece a mere link in a chain. Far from it – it is a unique artwork, formalized, materialised and dimensioned ad hoc for this specific, selectively calculated installation.

Indeed, the representation of La rendición de Breda is an outstanding leitmotiv of Miró’s Las Lanzas period. Just as other artists took to different referential themes in their works – quoting or paying homage to them, assiduously and reliably, during their respective creative careers – so did Antoni Miró. The work under discussion, which explicitly celebrates the 300 years of that dramatic situation of a war that is forever inscribed into our collective history, is a paradigmatic example of precisely this tendency.

Today, (October 2013), we find ourselves in a critical-artistic situation in which creativity itself is often conceived and deployed in the world of contemporary aesthetic investigation. Within this versatile program, originality and/or innovation can be identified methodologically by way of re-readings, homages, the d’après, reinterpretations, quotes and thematic retrievals. Such methodologies have become potent strategies and shared resources of artistic production in the global context, thus giving full force to both the expectations of globalization and to the persistent options of identification, which move – with ease and determination – within the shared systems of artistic communication currently in force.

We have followed, assiduously and with interest, the development of the aesthetic and artistic career of the artist under discussion. Miró certainly has a wide and worthy professional curriculum, as well as an extensive bibliography in both books and print media. Within our speciality we have frequently analysed his works. These are made in a variety of media and spaces, but are always inscribed with an intense social realism and a strong awareness of diachronic roots and historical responsibility in their various executions. We know the artist’s different phases and diversifications, having written about them on many occasions, as we have with numerous other artists. We refer to these closely in our teaching, management, critical exercise, research and publishing, and have done for over 40 years in this profession, which we have practiced in three universities.

For all these reasons, we wish to underline the fact that – aside from the other issues and points raised – moving an artwork that has been carefully integrated into a public space with the relevant consensus of the time (as noted above) entails altering the artwork’s own characteristics, as well as those of its specific conception, construction and installation. It is also important to take into account the architectural challenges presented by the construction of the solid foundation – requiring a 30-ton piece – the purpose of which is to ensure that the sculpture stands out against the green grass and blue horizon, in all its ochre and intense ferruginous chromaticism, with its barred counterpoints of red that so expressively lengthen its dilated forms. It is an exemplary display of apt, impressive and effective installation.

Therefore, it is in the artist’s moral property rights over the unity and totality of the work that the piece’s vital aesthetic integrity is based. In fact, we reiterate that the artist must always be consulted before any readjustment, conservation project, variation study or subsequent renovation is carried out on the artwork; this includes the landscape values of the artwork’s integration into its environment.

We also stress the essential relationship – experienced through mutual dialogues and exchanges – between the historical-cultural dimension and the socio-political dimension of our civic existence. Both these dimensions must conform coherently within a unique context of civility and coexistence. Politics undoubtedly needs the air of culture, and culture – especially in its public form – cannot be exempt from political support, respect and responsibility that, through committed action, ensures freedom of creation in the face of collective development, which social plenitude demands and makes possible. The moral rights of the author over the work demand, as we have stressed and reiterated, a consensual agreement to any potential alteration to, and/or maintenance of, the artistic values – joint and pluralistic – of the sculpture, 25 de abril, 1707 – values which emanate from, and are aesthetically reinforced by, the work’s public installation.

València, 23 October 2013.

(Legal report, officially presented at the relevant trial).