La famosa Gioconda (The famous Mona Lisa)

La Gioconda a L’Havana

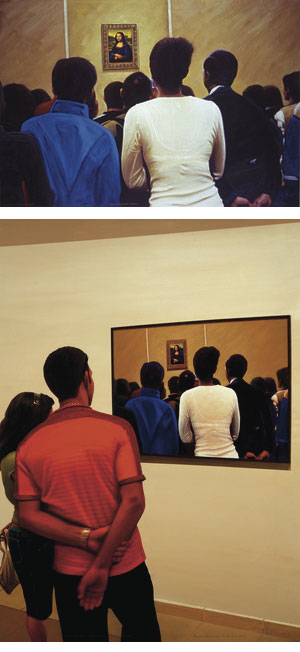

These two works clearly deserve to be considered together. Both spark interest in meta-painting and use identical conceptual strategies, and furthermore, are based on the same canonical work: the portrait of La Gioconda [The Mona Lisa]. Throughout his artistic career, Miró has spent a lot of time in re-interpreting canonical works. In the 1980s and 1990s, he did so by altering and juxtaposing fragments of High Culture works in order to come up with ironic new proposals. In his more recent works focusing on museums, these canonical works are incorporated as self-standing pieces without transformations or biased approaches.

In both cases the work reflects on the viewing of art and the dialectical dynamic arising therefrom. On the one hand, there is the first mutual gaze between Leonardo and his model during the creation of the original, compared to the gaze of the onlookers at the delicate, enigmatic Renaissance portrait. On the other hand, the works compare public appreciation of Leonardo’s masterpiece at two very different museums — the Louvre and Havana’s Museum of Fine Arts. In the first case, the piece shows how the public see this extraordinary work. In the second, we see a different kind of viewing in which much greater stress is laid on the act of appreciation of art itself, and much less on the piece of art. Miró’s two works thus are two linked essays on the functionality of the picture within a picture approach, and on the depiction of the action of viewing art nowadays.

One should recall that aesthetic enjoyment stems from leisurely observation. Yet the situation in museums is a paradoxical one given the clash between a given advantageous situation, the opportunity of enjoying valuable works, and the possibility that the conditions of appreciation may not be fitting. Miró’s works show this circumstance, while a commodification of the referent is produced — a typical resort of Pop Art. He is thus highly critical of the mass-consumption of our culture’s iconic masterpieces.

In fact, there is another difference that goes beyond the merely geographical. The two museums are different; as are the societies they serve. Maybe this is why the orientation of the canvases varies: vertical in the original portrait, horizontal in the representation of the first intertwined gazes, and vertical again to introduce a new turn of the screw. The whole thing is thus a game of gazes: the blank stare of Leonardo, that of the European viewers upon the masterwork, and that of the Cuban onlookers, from a new background, upon the humdrum scene at the Louvre in the exceptional presence of the Mona Lisa, which in turn spawns a new work with its own entity.

Santiago Pastor Vila