Gran ciutat-dipòsit (Large city-cum-depository)

As Ricard Huerta writes, Antoni Miró “feels like an urbanite in his condition of artist”. Miró clearly recognises the city as a political space, and much of his output in the first two decades of the 21st century covers the city as either a theme in itself or as the frame for our history — something that is only natural given that Miró is “an artist of critical awareness”, as Fernando Castro defines him.

This is one of the works that falls in the first category (the contemporary city as a theme). In it, he does not feature, except with concealed references or in an implicit way, “men and women living alone, gazing upon the world alone, and begging for alms, revealing the depths of misery of an alienation unworthy of humanity”, as Josep Sou put it.

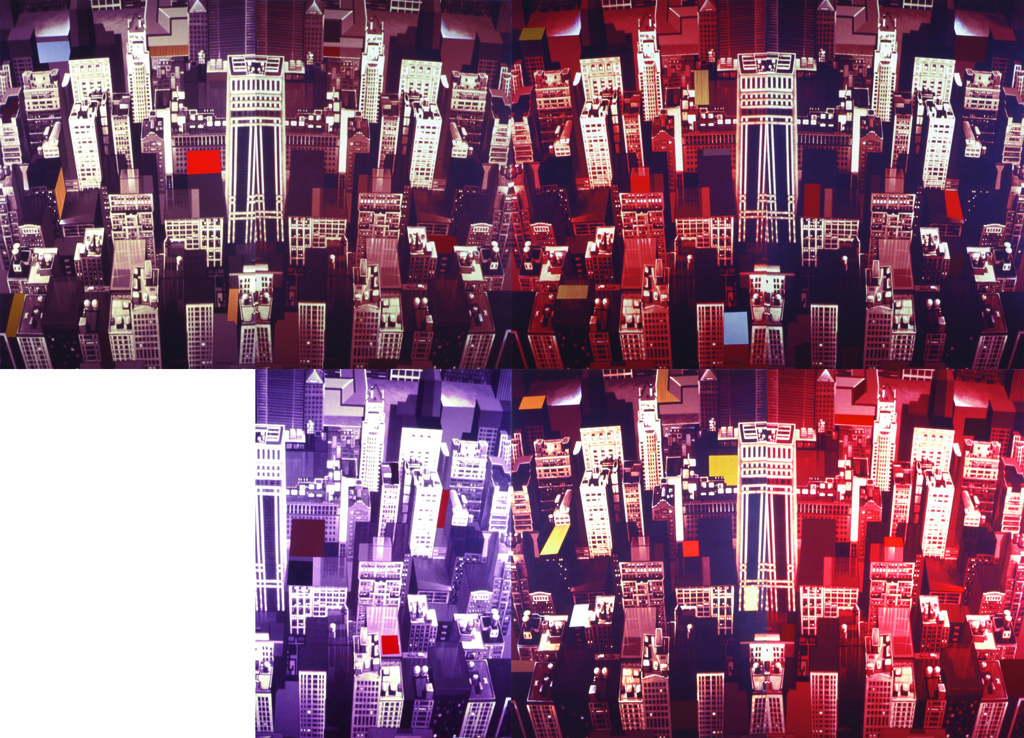

Instead, he gives us a view of New York as a city that has almost been commoditised. The artist explains through this panel-painting how a fragment of the better-known downtown area of the USA can end up being a self-spawning element. Firstly, he reverses it symmetrically, and then this pair of images (the original and its symmetric counterpart) are, in turn, added to more pairs of images. This is repeated to form an image akin to a likely reality.

To sum it up, as if the cityscape was a fractal entity, one part resembles the whole thing on its own, and when it assembles and forms a more complexentity, it keeps the same appearance as the first fragment. This artificial confrontation of a representative base is what provides the city with the capacity to refer to a concrete tipology, even if it does it under generic terms. This process explains why the financial centres of the world’s capital cities have a shared substrate that defines them, but that also makes them hard to tell apart at first glance.

The regularity of the scheme, the extraordinary building density to exploit every last square foot of land in city-centres, and the lack of empty spaces for public use and green spaces combine to create a strong homogenising effect. This makes it hard to distinguish buildings by types and layouts.

The work clearly shows the successive juxtapositions made to leave one of the eight panels making up the canvas free. This signifies: (1) the form and size of the base units; (2) the way the images have been flipped. Once we are familiar with the unit and the combination procedure, one can create another generic reality from scratch.

The latter is what differentiates each sector. Each of the seven panels containing images is based on grey tones with slight colour deviations yielding coloured areas that stand out. These coloured areas, which go unnoticed at first glance, appear as singular elements over the texture that ends up forming the base image.

It is as if the painter, through this act of singularisation, came up with a composition that is the sum of the truly distinct elements, and, consequently, a new great city was born, hosting multiple vital processes that are both so similar and yet different, even though they were not noticeable in the beginning.

Santiago Pastor Vila