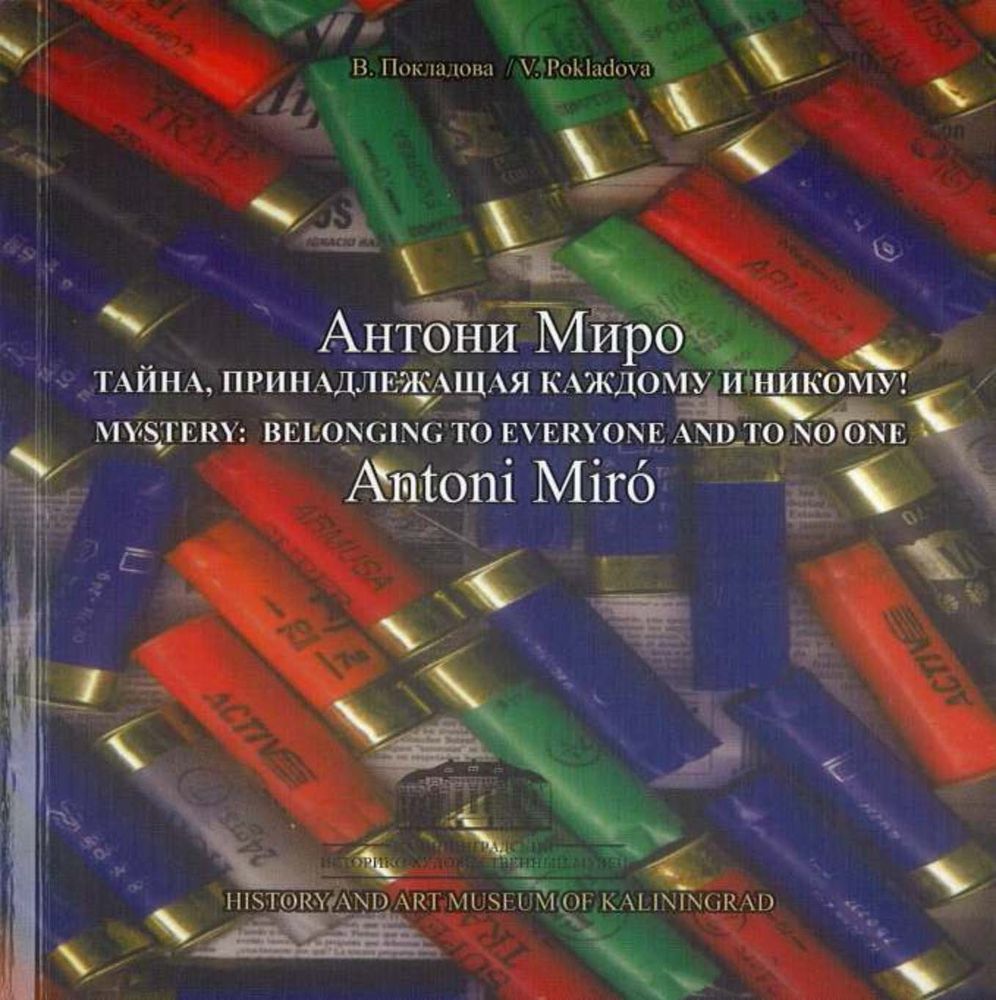

Mystery: belonging to everyone and to no one

Valentina Pokladova

“Mystery is not at the beginning and not at the end, it is in reality. There was never any beginning, and there will be no end.”

J. Fowls “Aristos”

The favourite question of our time is: what is art? What is the subject of art? These days it seems impossible to take sides for cubism, expressionism, surrealism, etc., and to be able to decisively declare: this is modern art. The Spanish philosopher, José Ortega у Gasset, wrote in 1916, “every experience of preference opens emptiness in our soul. Let us not make preferences. Let us prefer not to prefer. Only then does life gain sense, when the aim is not to practise self-denial.” Artists, being aware of the spirit of their time, choose the position of the spirit, which stops nowhere, is unattached, and hovers over different possibilities.

The unpredictable spirit of Antoni Miró lives in the space of intellect, with endless research of the past, which then becomes a metaphor of reality. The current interest in art for many people coincides with a new perception of the shortness of time given us in eternity. Everything once called immortal is mortal; time is eclipsed by nuclear catastrophe. Therefore, great is the role of the artist who nourishes culture. Practically, Miró is Kantian; he believes not in natural kindness, but in culture. He substitutes nature for the person, appeals to human spirituality, tells the truth that one wants to keep hidden. His series of lithographs “Viatge interior” continue to speculate on the fact that common notions of world stability are again destroyed, sense and moral postulates are decayed and the disrupted civilization looks withered by rationalism and neurotic due to prejudice. An apocalypse not only occurs in the universe, but also in a grain of sand, a drop of water, in a molecule, and eventually in us.

"Eternity is necessary to create spiritual culture, but only a moment is needed to destroy it.” (T. Mann, “Death in Venice”). A man ascends to the kindness of idea slowly and with great effort, but the process of degradation is quick and disastrous. The multiplicity of Freudian images used by Miró emphasizes the inviolacy of the scientist’s postulates about spiritual life: there is always conflict between the unconscious and the many prohibitions made by the mind, and only art can resolve this conflict.

The essential condition is for it to open hatches into the hidden field of a human mind and to shine on it increased knowledge. It will probably not change the character of forces acting in the unconscious, but it will help to fight against them.

“A man is a rope, strained between an animal and a superman, a rope above an abyss. It is dangerous to pass, to look back —both fearing and stopping are dangerous. It is important for a man to be a bridge, but not an aim; a man is an overpass and death. Only these things can be loved in a man.” (F. Nietsche)

In Miró’s images there is a constant teetering over an abyss: the tragic and the comic, the sublime and low, the real and fantastic. It is like a bullfight, when fiesta, art and custom meet to deceive death in the name of life. Who is in need of nonsense and for what purpose? Also pain, for understanding the completeness of an entity, for recognising the irremovable absurdity of the world, for regulating the chaos of life, for the circuit of poles. Miró, keeping faith with his teachers, states something that is not a copy of “reality,” but opens a wide expanse for interpretations —as one of the essential privileges for a man is to have his own opinion.

The contemplation of what you see does not give a key to the mystery, and perhaps there is no key. The artist often emphasizes that the idea of the pictured thing is not the thing itself: it is only paint on the canvas. Statuesque pictorial components are accomplished with hypothetical clarity, but where they are headed and why is not possible to explain. Words in the picture more often embarrass the spectator, for their ability to mislead is indeed surprising. They live by their own laws, they have their own links, and they depend too little on the things that represent them. “This is not a man.” “This is not a pipe.” “This is not Miró.” The visible is not always true. Eyes and intellect are shown the indefinite that comprises the kingdom of the visible, but in reality the work shows that we sometimes lack ideas.

Scenes with mirrors are not rare among artists. Does the look come back from the mirror? A moment of panic, but not an explanation, is important here; the experience of everyday nature itself is put to the question, and this experience was considered inviolable. In the whole world’s space everything is possible; and painting, graphic arts, sculpture use subject as an instrument of thought, philosophical wisdom, or a means of recognition.

The only things that don’t appear in Miró’s territory are popular opinions. Behind the word “pop” (as Richard Hamilton’s work was called, thus giving the name to the whole tendency) are other meanings: 1) a sharp sound, 2) a shot, 3) a fizzy drink. Actually, new parts performed by his personages/actors— our old acquaintances— shoot at spectators like a cork popping out of a bottle of champagne. The gods have created Miró as a playful man, capable of turning any banality into discovery— for instance, turning a normal bush into a Burning Bush.

The arrival of Miró’s lithography collection in Kalinigrad, Russia, a country the artist can hardly imagine, is in a way a creation of theatrical space, with everything and everyone becoming its participants—the artist’s works, local museums, spectators, faces, words, looks. Really, if everything surrounding you, civilization’s waste, can be art, and then why not consider yourselves participants in the Great Performance? Does any man in the crowd consider the possibility of suddenly finding himself a player in the mystery of this strange world, and not a passive viewer of TV programmes or reader of newspaper gossip?

In February 2004, the collection of Miró’s works was presented at the Historical Museum of Sovetsk (ex-Tilzit), in the region of Kalinigradskaya. The city has a structure of wonderful historic interest—the Queen Louise Bridge. Built in 1807, it saw the meeting of two emperors, Napoleon and Alexander I. It was blown up in 1944 and reconstructed in 1947, restored in 2003 for the 100th anniversary of the Tilzit Peace. It lacked one detail, the low relief of the queen, which was thought lost forever. But suddenly, a miracle! At the bottom of the river, through the depths of the water, the restorer saw a female face, the missing low relief.

It seems to me that this is an important detail of our performance. The days pass and will not return, but the past is still alive under the snow of years. It, like a spring that is eternal under the panoply of ice, in the spring containing our memories and our secrets, countless swimmers thrash about, twisting in the water. “It is important for a man to be a bridge.” Such is Miró.