Antoni Miró or the critique of the serene gaze

Rosalia Torrent

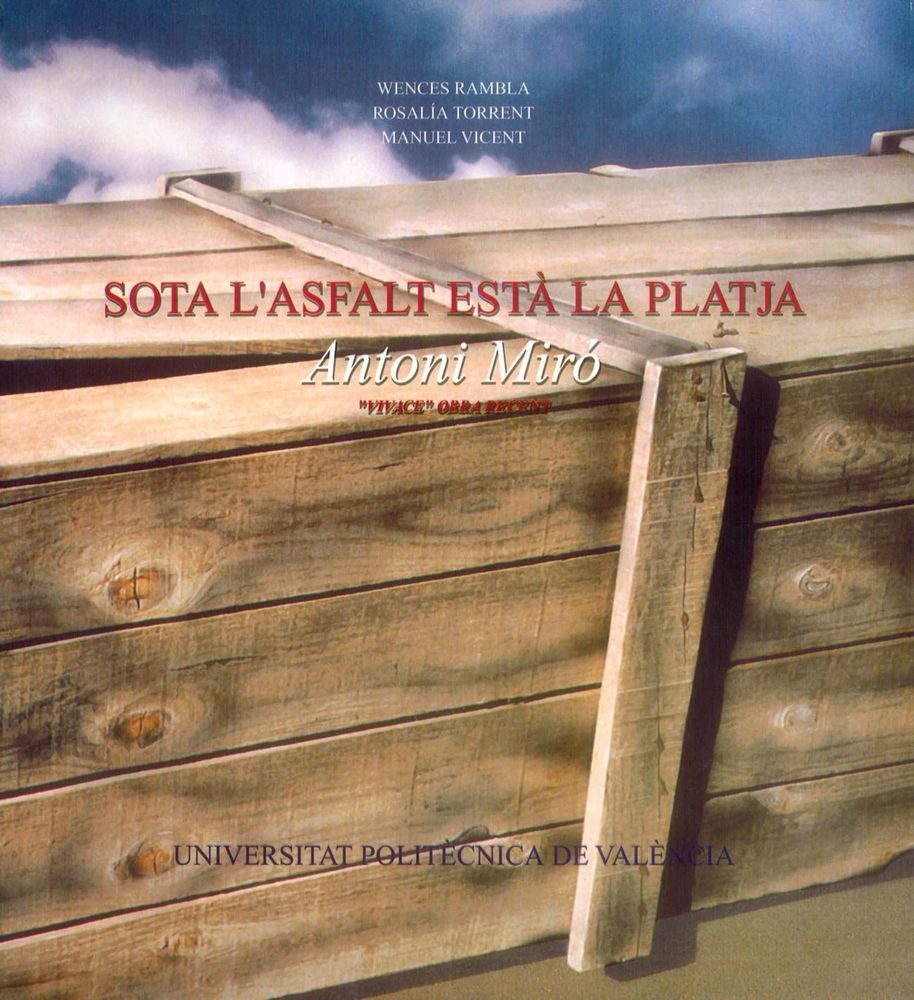

Reasons can best be defined with serenity. This is why the approach that we find in this series of works by Antoni Miró is the profound gaze of conviction. When we look at these bicycles looming up out of the mist, in the forests of a drowsy idyll, standing before these seas of deep colours or metamorphosing through the mixture of surreal imagery, what we are really experiencing is the commitment with nature, the wise lesson of telling it all as it is without describing this mimetically. There is a lot to disquiet us in Miró’s lucid proposals, so much so that the landscapes hurt with the latent fear of their disappearance, perhaps, as transcribed here, brought about by the relentless advance of tarmac, a dangerous metaphor of a civilisation with no culture.

The beach will indeed perhaps be under the tarmac some day, and perhaps the sand so complacent with summer and sweet somnolence might well be buried by the inevitable grey of industrial paths (so different from these paths trodden in the earth, drawn “blow by blow, verse by verse”). And this, perhaps, is what moves the painter’s conscience, what drives him to fight against probability, what moves him to exhibit his woks for these to fight against the grey desserts, this time in a delicious metaphor of a civilisation which believes in the culture-nature equation.

It was this powerful metaphorical content in Antoni Miró’s work which one day led us to ask him for one of his paintings to act as a reference for a summer course on journeys that we were arranging at Castelló University. This represented -of course- a bicycle! This bicycle with its metal parts, so charmingly held still in the landscape for us to hold still before this, did not contravene the poetry of the autumn setting. Instead, melting into this, did mysterious and warm, it still bore the trace of the person who had recently been pedalling is along and who finally, full of “Empordà i de boira” (Empordà and Mist, the two references given us by the title) had left this alive beside the wood, mysteriously upright and contemplative, for it took to be able to have its moment of ecstasy.

If I have brought this story up once more this is because I think it clearly sums up some of the sensations that a spectator can feel when faced with certain works by the artist now in question. At that time those of us, who looked at his paintings, seeking the definitive image to represent our course, saw a perfect symbol of the traveller, whose ultimate purpose would be to stop to look. And what any such traveller really wishes to find is undoubtedly everything in its place: trees in the wood, colours in the sky, sand on the beach. There are indeed asphalted cities, but the city might well be suited by asphalt, though not places that contemplates landscapes, not spaces which cry out nature. In this respect, Miró’s image, like so many others of his images, was upholding the need for the necessary pause, resting the gaze on a beauty not devoid of mystery.

This mystery drinks from the serene disquiet -as mentioned above- which does not return us the pleasure of what is simply known; and this is where we find the painter with resources, one who has things to say and knows how to say them in a unquestionably personal way. These works should be related, rather than with the pop discourse, though this is no doubt present, with surrealist and metaphysical approaches, both through their highly dreamlike content and their suggestive power. Not in vain does Miró recognise Magritte, not in vain does one find in Miró reminiscences of Giorgio de Chirico. Along with these there is Dadaist irony, that which led him to compose another of the items that appealed to us when seeking a work to cover the wide ranging spectrum of the world of travel: that suitcase that he himself called Dada, whose “urgent” label stuck to one of its sides contrasted with the setting in which the onlooker finds this, by a Castilian-looking hill. Alone, as if it were abandoned and nevertheless telling us that man gets as far as this and has once again decided to stop and look here. Any belongings will fit in Miró’s cases, but the most immediate sort is the questions that they generate: any traveller can pedal their vehicles, often strange, but for each different person the destination or the time will be different because their images seem to be left hanging in the air, held still in existential space and giving their spectators time to see, time to think, time to know and feel that they are different.

It is a well known fact that Antoni Miró has covered a wide range of themes and modes over the last few decades. He once appealed to us through his social commitment, his clear ethical stance. Now, with those times of tragic unrest fortunately far away, he nevertheless keeps his commitment intact, devoted amongst other works to different themes, to this sort of series of journeys with no apparent travellers, only hinted at through the object which makes them move ahead. I personally find today the Miró who says most to me in these bicycles, in this motion loving forms, in one if these ships that he gives us as a present, waiting for us somewhere. The desire to take flight might be something present in all of us, and perhaps we should all like to have faithful companions in the form of wheels, oars, skins or steamships, and maybe we would also like to be capable of halting at the place where the landscape endures, without the perverse hand of those who would like to smear it with their industrial grey.