The visual memory of a living cultural tradition: the Water Tribunal

Romà de la Calle

There are themes, events and traditions so rooted in everyday life that they can become fully identified with it and a substantial part of it and its imaginary contextuality.

In such a situation – as a determining proof of verification – the selective interventionism of the multiple and polyform artistic interdisciplinarity/intertextuality soon completes the consecrated aesthetic and symbolic ratification with its revulsive chore. Thereby increasing its documented representative status, becoming an essential part of its increased visual and literary memory.

This has happened, in its diachrony, with the Valencian Water Tribunal, an institution with a long history, which has been assumed testimonially and metonymically as a memorable image of a living and customary cultural tradition. It is a body that is well-known to be specifically linked to the administration of justice and exemplary functions of a self-managed government. These refer not only to the use and exploitation of irrigation water, but also to the network of irrigation channels and scheduled distribution periods, with their plexus of possible conflicts, diatribes and confrontations derived from the complex social and material interaction that all this socio-economic-cultural mesh entails.

The arts, often founded on the nourishing soil of history and the pride originating from the exceptionality of identity, have, therefore, continually documented – through their reproductive imagination, their singular artistic resources, as well as the diversified figurative procedures employed – a whole series of scenographic compositions with a special narrative force and supervening connotations around the paradigmatic theme.

Let us recall, as a strict and opportune example, some of these historical contributions on the Water Tribunal. From the engravings by Gustavo Doré (1832-1883) to the paintings by Bernardo Ferrándiz (1835-1885), from the novel La barraca (The Cabin) by Blasco Ibáñez (1867-1928) to the engravings and watercolours by Ernesto Furió (1902-1995).

Also not forgetting, in this chain of outstanding effects, the series formed by an extensive travel literature. The authors came to these lands attracted, century after century, by the siren-call of the south and they became a sounding board and direct witness of this exceptional and original event. An event they necessarily recall in their correspondence, notes, studies and memories.

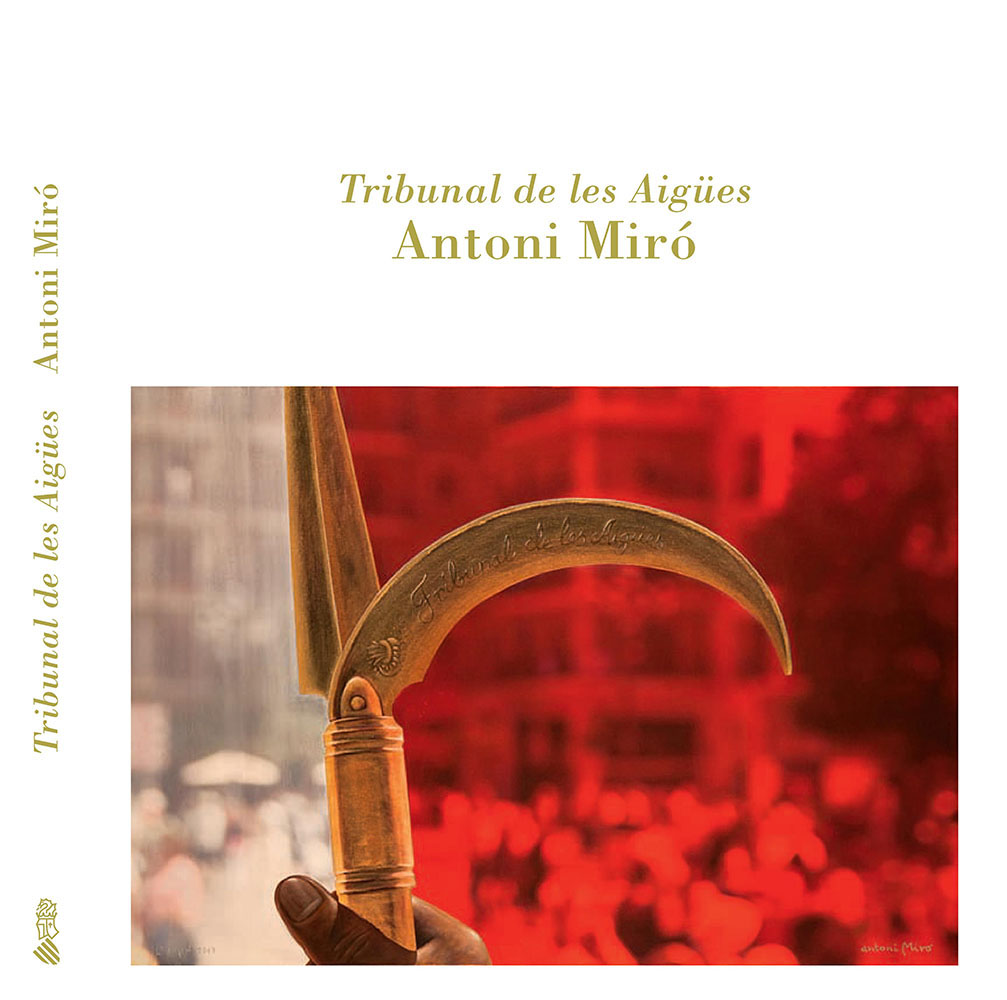

We must accept that, since the recent recognition of the prestigious institution by unesco – as shown by its registration as an Asset of Intangible Cultural Heritage on 30 September 2009 – there has not been such a broad and systematic series of paintings and graphic works, planned around a number of exhibitions, as the one that has now generated the intense and programmed artistic activity of Antoni Miró (Alcoi, 1944). His timely production documents the physical, social and cultural context of the Tribunal, which – it should be recalled – had already been designated as an Asset of Cultural Interest (BIC) by the Generalitat Valenciana in 2006, as part of its axiological reinforcement of our historical, material and immaterial assets.

What were unesco’s objectives in this designation? In fact, the international standard and the facilitated programme are, historically, based around four basic axes that become, in turn, objectives of the nominative strategy: “a) safeguarding intangible cultural heritage; b) ensuring respect for the intangible cultural heritage by the communities, groups and individuals concerned; c) raising awareness regarding the importance of the intangible cultural heritage at the local, national and international level and promoting mutual knowledge; and finally, d) establishing close cooperation, providing assistance and support, at the international level”.

This Intangible Cultural Heritage, which is transmitted diachronically from generation to generation, is constantly recreated/maintained by communities and groups, depending on their environment and in close interaction with nature and their history. Without a doubt, it is a basic resource for instilling a sense of personal and collective identity in citizens, as well as ensuring the continuance of a testimony to continuity and shared memory, contributing, in this way, to promoting the necessary respect for cultural diversity and sustained human creativity.

In this sense, the artistic decision of Antoni Miró remains in line with his long record of evident cultural interventionism, in full habitual linkage with his numerous documentary proposals and closely linked to the contextualisation/recovery of lived historical events.

Undoubtedly, it is an effective way to turn our gaze on the territory, to inculcate environmental sensitivity and collective responsibility, to facilitate citizens’ re-encounter with their own landscape and to remove, if possible, the background of the collective imaginary, restoring/increasing, as much as possible, the shared affection for the land.

Antoni Miró is a persistent and obstinate socio-cultural reporter of his existential environment and he is self-conscious in the transcendence that the interventionist commitment can acquire in the collective memory. In each of his artistic series he has always given precedence to convergent responsibility, which integrates and stimulates the receiver, beyond their gaze. He wishes to transfer/attract this gaze to the narrative core of the exhibition planning, jointly motivating the activation of the viewer’s imagination and consciousness.

This happens in this quite extensive series entirely centred on the long shadow cast by the Water Tribunal, which, as usual, in his figurative poetics methodically starts from the selective and precise photographic gaze to, then, jump, as a strategic resource, to pictorial development and digital graphic composition/printing and even screen printing.

I have always thought that the proper way to understand/generate the meaning of images – as in the case of texts – is to involve a kind of – dense or light – semantic penumbra, differentiated according to the case. In fact, this singular and unique penumbra/resonance is where, at its widest, the context takes root that gives strength and solidity to the weave of its possible meanings.

In fact, in Antoni Miró’s work, beyond the structures, forms, chromatisms, contrasts and materials used in the syntactic composition of the images, there is also the neat shadow of his semantic charge: that is, the set of his particular ideological resources, his documentary claw, his connotative background and his shared memory repository.

Without this global substrate – complementary and even, secretly but effectively clutched to the rotundity of his syntax – the constructive games of the images would be solved in pure formalisms that, being indispensable essential – let us be aesthetically clear – are not, after all, sufficient in their, perhaps, impressive artistic functionality.

Such semantic obscurity implies the convergent contribution of the authorial charge and that of the context, as well as that of the history and the educational support. However, it also implies the convergent contribution of the viewer’s gaze and his own subjective backpack, as a special guest to the interpretative evening of each piece, daringly exposed to the battle of hermeneutic attrition.

Antoni Miró’s skilful planning of this series has approached the realisation of the entirety of the Water Tribunal by presenting it, in his reading, as a procedural series of snapshots. There has always been and there still is a lot of cinematic heritage in his visual proposals, both in the individualised composition of each of the works and in the joint resolution of the staging of the series.

Also, in this case, and in this narrative visit to the Tribunal and its territories, the decisive imposition of the pan-shot of an invisible camera is evident. It selects the shots and prioritising frames, focusses and documentary still shots. There are, obviously, the resources of frontality, bird’s-eye views, oblique perspectives and close-ups, along with details and simulated tracking shots, in his huge descriptive power, which will be fragmented in relation to their visual efficiency and possible commitment.

The series undoubtedly contains paradigmatically emblematic scenes, either because of the representative scope of their characters (Els síndics [The Trustees], L’alguatzil [The Sheriff]) or for their characteristic framing (Apòstols de pedra [Stone Apostles], Portal [Door], El cercat [The Fence], Expectació [Expectation], El corralet [The Enclosure] or Rètol [The Sign]). However, there is also no lack of thoughtful supplementation sequences that place other locations, close or remote (Casa Vestuari [Robing House], Arc romà [Roman Arch], Partidor [Distributor], Assut [Dam], Molí d’Aroqui [Aroqui Mill] or Séquia de… [Channel of…]). The eloquent aim is to present structures and landscapes, channelling and distribution services belonging to the historic water distribution system that so significantly embraces the Valencian territory, making it into a common body.

The Tribunal is a key to our identity and identification, it has in many ways become an eloquent synecdoche for our land. Antoni Miró’s paintings are well characterised and full of self-consciousness and by playing the part for the whole he has been able to assimilate, as a strategic lesson, both an artistic language and the elongated semantic penumbra we have talked about in our previous and parallel reflections.

Water, as a metaphor of shared and normalised life, has generated, in its diachronic territorial course, not only an architectural layout and a self-regulating service, but it has also managed to promote the parallel institutions required for governance and the effective functioning of its agrarian existence and its urban consolidation. Intense dialogues between the countryside and the city, between production and the market. Links between history and the present, between symbolic power and legal effectiveness, between the identity of a people and the pragmatic consistency of a territory.

The old adage – firmly rooted in the heritage of our classical tradition – that reads “Natura artis magistra” has been declining, in its persistent use, until it has transform itself, by studying its own course, into “Historia artis magistra”, beyond or more than the usual “Historia magistra vitae”. That is, we find ourselves rediscovering art as the fruit of lived stories, as the result of the persistent rereading of the contemplated images, when all is said and done, as a definitive applied iconography.

Water Tribunal, therefore, becomes much more than a reason, an advisable moment/mirror for recalling a whole lesson in coexistence and civility that the shared temporality has bequeathed us, with its exemplary capacity that can perhaps also be extrapolated mutatis mutandis to other segments of our existence

In this challenge, which has been sustained over centuries, the pictorial action has intermittently felt invited/obliged to look at the experimental resonance of such a common lesson and document, making its own, each time in its own way.

This is perhaps why Antoni Miró did not want to miss this appointment to the point of forcing his images to be authentic conceptual landscapes enmeshed in everyday life; to become revisited visual reflections in which nature, history and culture go hand in hand. This is why he wanted us to return from the known city (a concrete corner saturated with history) to the recovered countryside, the territory of identity, to the memory of places, to the life of the water, successfully commemorated in his perpetual capacity for transformation.