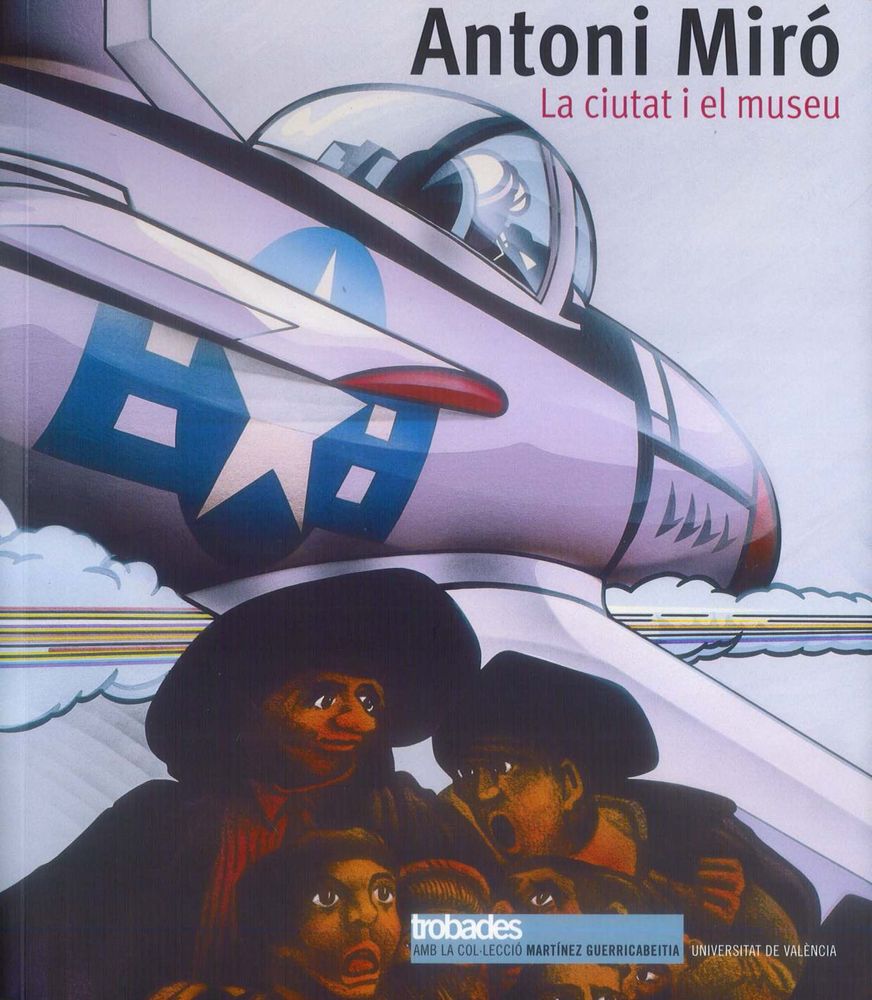

The city and museum

Ricard Huerta

The city smell

We can detect the city’s presence from a certain distance. This perception is not solely visual. The sound and the polluted air also reach us. We get the feeling that we are being absorbed by a tangled mass of reverberations. We know that there is life there, that contradictions seethe in an ecstasy of conflicts. And this very same feeling seems attractive due to its impact. We close in on the areas branching out of the urban concentration and begin to pass through a series of hybrid zones that are, in the end, sordid. Nevertheless, here on the industrial estates, wastelands, ruins, debris, rubbish dumps, petrol stations... A barrier that is by no means psychological warns us of our arrival at the limits: the big advertising hoardings begin to flood the way. The trees recede and the colour plants die out; the fertile dominion of greys begins, obstructed by fireworks and lively tones of advertising claims.

The city has its own laws. The agglomerations characterise and define the way it looks. Everything is accumulated in the city’s environment. Rhythms exist through accumulation. People, buildings, dynamics, wealth, poverty, misery, ostentation, night’s lights, day’s shadows, injustice. Everything spins and everything moves in this show created by the urban agglomeration. Although Antoni Miró has chosen, both as a personal decision and a way of life, to distance himself from this urban show by making his daily habitat a place far from the city, the fact is that he feels himself to be an urbanite artistically. Although he confesses having little to do with the histrionic profile of the city, he doesn’t want to lose touch completely with this reality attracting him overwhelmingly through its conflicts and peculiarities. Years ago he decided to move out of the city and get away from the noise to a farmhouse rooted in the country. A tense road (now they are called motorways due to their characteristic lane layout) has come to cross this spot at a tangent in Mas Sopalmo, an almost venerable place. It is clear that, in spite of the painter’s decision to live away from agglomerations, Antoni Miró feels greatly attracted to the city, and especially to its problems, but also to its museums and people. In some of his series, including his latest work, this interest is sharply noticeable. In his pictures we can see the view of the observer, the tourist, the lodger. For Antoni Miró, the reality cities show is a generous well of images and ideas, of portraits worth to rebuild. The inequalities and belligerence of the most disadvantaged sectors of society also appear in his paintings, true clippings from urban imagery.

A container of culture and disorder

The city has always been of interest to artists. One classic reference could be La città ideale ("The ideal city"), the painting considered for centuries to be the work of Piero della Francesca, which hangs in the Palazzo Ducale de Urbino. It has recently been attributed to the architect Luciano Laurana, who worked for the Duke Federico Montefeltro. It is the art historian Walter Hanak who has most insisted on the theory in favour of Luciano Laurana, since at that moment in the history of the Renaissance Laurana was working on the construction of the magnificent Palazzo Ducale de Urbino, a space created in the painting which has certain similarities of proportions to the public spaces created by Urbino himself.

As a projection of their own ideas, or as historical documents, visual representations of the urban environment have been of constant interest to the artists, architects and engineers who have created them over the centuries. And not only as a graphic resource. In both literature and music to the city has been a fertile source for plots and reasoning, thus transforming interest in agglomerations into a key element for artistic creation. Idealised, venerated or re-planned, the cities that have attracted artists’ attention show us a reality that has been forged in relation to the gradual growth in population. This growth soared in the 19th century with industrialisation, and since then until now has never ceased in its efforts to achieve a growth without a limit. Right now, some artists have centred their attention on the outskirts, as in the case of Juan Ugalde. We can also observe in the works of Edward Ruscha this passion for the outskirts: car parks, petrol stations, streets and motorways, nearby mountains; these are some of the focal points of attention of this North American artist who has given such a superb account of his fetish city: Los Angeles. In the case of Antoni Miró, the limit is in eviction, inequality or uncertainty.

Summarising among modernist movements, so fond of working with urban spaces, it is worth remembering the interest of artists from historic vanguard movements like Die Brücke or Der Blaue Reiter, and of course all of the expressionist movement installed in Berlin between the Wars, as one of the most characteristic focal points of attention with respect to the city. The street scenes by the painter Ludwig Kirschner, as well as his companions of his group and tendency Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Erich Heckel or Emil Nolde, bring us nearer to an environmental reality that is still faithfully depicting some of the distinctive elements of urban uneasiness. Paris, London, Tokyo and New York have for years been meeting points for artists who have captured the fascination for the urban show in their work. Painting, drawing, cinema and the media, including the latest technology, all reveal the artists’ enthusiasm for the image of the city as their focus of creative attention. In this whirlpool of interpretation we find the detailed brush strokes of Antoni Miró capturing chosen fragments of his preferred cities. And despite being a spectator, this painter does not limit his perceptions to mere portraits, but recovers aspects of which he is critical and presents them to us crudely and clearly. We can see a decisive moment in the reading the artist has made of the city which greatly affects his urban tale: the attack on the Twin Towers in New York on September 11th 2001. Obviously, a crucial event, with which a new concept of world disorder began, as well as a new century and millennium, could only affect the painter, who since then has handled his urban descriptions with emphasis, uncovering the asphalt material of his themes.

Antoni Miró’s works appear to us here as a generous source of visual data which we could call a sociological study of the history of the citizen’s painting. They come to represent a kind of tale in images of events very close to the public (and the narrator) due to their appearance in the media, a sort of roar from the media that the painter studies in detail in his explicit compositions. Thanks to the lively colours from the Alcoy painter’s palette, we immerse ourselves in the fragments of reality that we have already devoured in the media, but which now seem to be settled in a frozen image, of pictum (just as Barthes described it) that depicts the imposing reality of death from the standpoint of the busy experience he lived through. It is the struggle to eradicate so much disorder that helps Antoni Miró to keep motivating us with his compositions.

We know that the city is home of all elements of power established by the state in modern centuries: military power based on the impetus of coercion, economic power based on the strength of capital, political power organised by authorities, and ideological power under the auspices of cultural influence, in fact one always talks about certain cities as "centres of power". For this reason, as responsible and critical citizens, we accept the challenge of participating with our ideas and effort in an attempt to improve relations with the prevailing powers in the city. The pictorial reflections of Antoni Miró cannot be seen as mere pamphlets about specific elements, but as true essays that question the domineering, exaggerated attitudes of the power against those who have not being not favoured by the consumer society. We cannot understand power as an unquestionable whole. On the contrary, we must create our own attractive arguments to take apart many modern myths on which the abuse of power is based.

The city and the museum as identifying spaces

Some cities have chosen to create spaces in their museums dedicated to urban life, in a play of mirrors forming a language to project. As a nearby example, in the Conde Duque Cultural Centre we can find a particular art collection, located in the Municipal Museum of Modern Art (Museo Municipal de Arte Contemporáneo) in Madrid. This stands out for having as a means of exchange among the pieces on display a scene of the city through which we can obtain a frame of artistic reflection. The collection gathered there contemplates some of the most outstanding names of artists in the Spanish panorama over recent years. However, its true value lies in the themes chosen as the nucleus of the collection: the city. In this museum’s rooms we can find important pieces from artists such as Andreu Alfaro, Carmen Calvo, Úrculo, Arroyo, etc., but in reality, their individual names and works end up forming a more complex framework. Thanks to this, we can immerse ourselves in the social and cultural detonators covering the city with two contrasting identities: ostentation as opposed to misery. Poles apart of the same diagram that in the end contains attractive nuances for always visitors. Beyond the urban politics that deepen the rift between social classes, beyond the arbitrary destruction and the business of speculation, the city keeps its pulse alive. Its people pulsate in this knot of interests of which they are partly victims, but also become actors in a script which is, in the end, much more loaded than one can presuppose in the beginning. The populace’s daily worries about urban uses keeps a lively pulse with the contradictions of the very stage of the city. The city streets become boxing rings designed for fighting, where each fighter opposes the rest of their neighbours in a clash of interests that end up forging a sea of new exchanges, the fruits of which leave no artist indifferent, who try to mould these complex exchanges of energy through their stylistic resources and their implication in civic, social and sympathetic processes. All of this, brings the creator to greater challenges in his attempt to capture what he also participates in.

As a symptom of complexity, the city is home to two bastions of social offerings: public and private spaces. As new typologies and cultures appear in our cities, we see how they feed on indicators that were previously known and even accepted. The traditionally autochthonous social group abandons public spaces to occupy new private presence. While the natives choose to occupy leisure zones, hypermarkets, multiplex cinemas and big shopping centres, the newly arrived move into public parks, streets and squares near their homes. This symptomatic, stratified location is perceived in the layout of the city zones. A district of València like Russafa becomes an ethnic legacy for many reasons, among which one should not forget the speculative interests that accompany the future project promised for years called Central Park (Parque Central). While the natives abandon parks and public spaces, those who arrived recently use this resource of the geographic surroundings to forge greater social ties. This question, taken to the extreme of ownership, seduces studious types because of its peculiarity. But the fact is that this contrast between public and private is still an exercise in the abilities of different social strata and classes.

The city roars and urges. The architecture of hunger

"The city is only uniform in appearance. Even its name sounds different from its different sectors. Nowhere but in dreams does someone still feel the most primitive way the phenomenon of limit as in the city. Knowing them means knowing these lines that, along the length of the railway tracks, houses, parks, or following riverbanks, run like dividing lines; it means knowing these limits as well as the enclaves of the different sectors. The limit flows like a threshold through the streets; a new sector starts as if tripping up, as we find ourselves on the lowest step which went unnoticed before."

(Benjamin, 2005: 115)

One of the most powerfully attractive features of the city is its propensity to change, its character as a frontier zone. The city is never definitive; it is a constant stream of transformations. In reality, the city is always under construction. This view of the unfinished scenery in Antoni Miró’s painting, even if the painter himself takes a specific look. The brushstrokes of the artist from Alcoy transmits us an instantaneous city, almost photographic, of incandescent colours, of digital reproduction, of chromatic contrasts set in the strength created by extremes, of margins broken by the sharp description of the edges. The city builds imbalances and inequalities, and in Antoni Miró’s works we are hit by the pleasure of the spectacle of contrast, in a reflection of social tones that instils value into his objects and perspectives, into his expectations of change. The painter captures the details out of sync that germinate everywhere on urban land. His ability to harmonise in decidedly constructed graphic compositions leads us to a portrait of a city where a possible unattended revolution of demands has been chosen as the spearhead.

We owe one of the most fascinating reflections written about the city to Walter Benjamin. It is an inconclusive essay in which we find data and ideas collected over thirteen years which the author gathered in Paris in the 19th century for the creation of his book, probably the emblem of the city par excellence. Meticulous and incisive, Benjamin gathers the most noticeable reasons for that which signified the emergence of the Paris of the passages. It is precisely the metaphor of the passage where the author is most incisive: the passage is a place of transit, the street, protected with its glass coverings that let light in; the passage is based on the commercial factor, an ideological source of the new political system; the architecture of iron revolutionises the possibility of creating pedestrian streets which were previously used by cars and horses; the passage introduces the fashion factor as a means of exchange, at the same time as it eliminates the prostitutes it has inside.

Fashion is not only distinctive for clothing, always more deeply rooted in the woman as the figure who translates and transmits her messages, but also as the determining factor of modern cultural and economic systems. The woman is part of this fashion system, taking advantage of the rise of its insignia. Meanwhile, fashion expresses a growing restriction in the private sphere. Through fashion, a rhythm of changes is imposed showing our propensity the need of urgent modifications. In the women portrayed by Antoni Miró, its uses bring with them codes. Permutations of social roles, or at least of their appearances. The creators of fashion move through society acquiring an image of it, participating in artistic life. Shop windows and magazines offer imitable archetypes and models. The search for harmony means celebrating the forms and colours that are "fashionable". Advertising wars are waged between fashion creators, companies and media moguls. As spectators, we watch a duel which in the end, is a struggle for economic control and for the creation of cultural standards, mythologies of taste. The media puts itself at the service of marketing. Multinational business fashion brands recreate discoveries made by marginal groups in their collections. Fashion trends are channelled, in the end, by the established order from their offices, who have in the media their natural ally. In the reflections of Benjamin (2005: 98): "Fashion is made solely of extremes. Given that it naturally looks for extremes, when it rescinds a certain form it has no choice but to surrender to the opposite (...). Its most radical extremes are: frivolity and death". In the words of Naomi Klein, author of the book No Logo, considered to be an authentic manual of the anti-globalisation activist, she never understood why her parents (who escaped to North America in the late seventies to settle in Canada, due to their antimilitary cause) never bought her a Barbie doll, a loaded object which ended up becoming a fetish in her own personal mythology.

City’s citizens. Silent Passers-by

The role of the visitor in the city is part of the framework of its streets, businesses and museums. The city takes in the tourist and the temporary worker, but also the disinherited. The threshold of poverty is the delirious margin of social circumstances. The urban map is not only made up of streets, squares and buildings, but also feeds on in equalities and intransigence. The lights of splendours opposed to the silence of exclusion. These are the ways of speculation. Any attempt to establish priorities of social assistance will quickly be tied down by the yearning for fast profits.

The solemnity of celebrated architectonic designs contrasts disproportionately with the affront that some districts suffer with structures generated for centuries by companies or groups which have been adjusting their needs to the opportunities of those who manoeuvre from positions of power. But speculation and its urban outrages habitually crosses the path of people or groups who try to resist, or at least protect their collective interests. In a city such as Valencia, at this moment in time, the identifying panorama feeds on healthy and sensitive processes. Like seeds scattered on the urban land, entities are born to conserve heritage and ownership, making claims for their idiosyncrasy. In an attempt to save their particular peculiarities and mythologies, these groups activate their ability to gather support: Salvem el Cabanyal (Save Cabanyal), Salvem la Punta, Per l’Horta, Salvem el Botànic... The artists’ voice becomes one more element, or even a key piece (Cabanyal Portes Obertes) in the web of new interpretations and defences. Against the so-called shady areas, spaces that are usually left unprotected behind the uncontrolled urbanising assault, social organisations demand a greater interest in generating inhabitable spaces for exchange, designed for the citizens.

According to Benjamin, when referring to the great transformations carried out by Haussmann in Paris, he states that their urban ideal was the perspectives opened up through long straight roads. This trend established by Haussmann corresponded to the desire to do credit to technical needs through artistic planning. In fact, "the bourgeoisie’s centres of mundane and spiritual control find their apotheosis in the framework of great public avenues, which were covered with a great canvas before being finished, to be uncovered later as if it were a monument" (Benjamin, 2005: 47). Paris in the 19th century was experiencing a blooming of speculation. Haussmann’s expropriations breathed life into the most fraudulent speculation. A speech by Haussmann himself in 1864 expressed his loathing for the rootless people of the great city. This uprooted population grew continually due to the establishment of companies. Rent price rises and dragged the proletariat to the suburbs and slums. Haussmann came to declare himself a “demolition artist”. In the midst of this panorama of forced evictions, the Parisians themselves began to feel alienated from their own city, and began to become aware of the inhuman character of the big city. For Benjamin, the real aim of Haussmann’s work was to protect the city from a civil war. He wanted to put an end to the possibility of raising barricades. However the barricades had a part in the February revolution (Benjamin, 2005: 47). The barricade appeared again with the Commune, and we, in modern times, are witnessing that a century after the Haussmannisation of Paris, university students, together with the most demanding groups in the intellectual, working class and trade union panorama, put up the great belligerently ideological barrier that we have come to know as May of ‘68.

In the city’s details signalled by Antoni Miró we find the layout pieces upon which the flame of critical reflection floats. Women, demonstrators, beggars, tourists, buildings, museums, advertisements, shop windows... Permeable liquids that move like flows of constant transformation. It is about changes, vital exercises that transmit a network of interests and that only the artist is able to put in order through creative mechanisms. Glimmers of what Walter Benjamin had unmasked eighty years before: "The beginning is signalled by architecture as a piece of engineering work. This is followed by a natural reproduction like a photograph. Creative imagination gets ready to be practical through publicity drawings. Literary creation, in the leaflet or brochure, takes part in the set-up. All of these products are about to submit themselves to the market as marketing products. But they hesitate on the threshold. From this age come the landscapes and the interior views, the exhibition halls and the panoramas. They are the remains of a dream world. The use of dream elements on waking is the classic example of dialectic thinking. Thus dialectic thinking is the organ of historical awakening. Every age not only dreams of the next, but also dreams while sleepwalking forward until the awakening." (Benjamin, 2005: 49). We take it that the graphic arguments of the painter Antoni Miró, as well as his marked ideological affinities, accept the dialectic mechanisms in the same way that they themselves are the result of a series of geographic and historical coincidences. Thus, we can establish parallels which help us understanding the message that is transversal in all senses.

We cannot avoid comparisons of cities and historical moments. The Paris that Benjamin talks about, the result of the economic upsurge brought about initially by the textile industry, coincides with a productive moment (in all senses) in the city of Alcoy, Antoni Miró’s native city. Nor is it a coincidence that Alcoy was for decades a crucial enclave for international meetings of workers’ movements, especially anarchists. Alcoy’s working class traditions form one of the most important socio-political arguments in the Mediterranean countries. At specific moments, as a focal point of tension, all Europe looked expectantly towards Alcoy in the light of the events that were taking place there. Meanwhile, the textile industry gave way to other profitable businesses, among which the metallurgical industry stands out. As the Alcoy’s paper industry opened up internationally, it brought along an explosion of ideas and far-reaching workers’ claims. In the sphere of artistic production, the vitality of initiatives carried out in this city of the central counties of the Valencian Country has produced a very particular element: commercial painting. There are hundreds of commercial painters based in Alcoy. This is a cultural industry which bases its economy on exportation. As an artistic phenomenon, it is a topic which has yet to be studied, but which is clearly tied in with the human factor (entrepreneurial spirit), with international business relations, and of course, with creative ability and self-discipline from the working class legacy. The auratic state or possibility of such productions is, as we have indicated, an element still to be analysed. We can note, as an evaluating indicator that in commercial painting there are no components making demands.

Although we initially saw Antoni Miró as a privileged observer of the city, as an interpreter of its ins and outs, the fact is that in the works of the painter from Alcoy, we can find enough details to put together a significant framework of his fighting character. This comes across not only as a pictorially attractive postcard of his travels and passions, but above all, as an energetic stance against colluding silence. The painter’s voice is the poet’s complaint. Action on canvas is a challenge, a declaration of principles.

The artist portraits of the museum

Antoni Miró offers us his particular vision of the visited museums. In this way, the artist comes to the institution that museums represent as a spectator, but at the same time, transfers to his pictures the experience, narrating his own experience. We find, then, a new model of the play of mirrors, of the inverted view, of the confluence of interests and combined interpretations between those who look and those who are observed. The operation has constant repercussions. We, as spectators in the pieces by Miró, put ourselves into redirected surroundings, since there is the possibility of seeing the painter’s works, again, in the museum.

Museums and art centres have become a type of advertising institution. At the petition of the most varied policies, the museum is seen as the most attractive image that city councils, governments and even multinational companies possess. Moreover, the museum generates much media expectation, since the events performed there (exhibitions, conferences, projections, meetings, congresses, presentations) become first class material for the media. In the end, this has obvious repercussions in the museum’s communicative ability, which thus becomes an informative and cultural platform revered by all. In recent years we have seen a giddying proliferation of museums, many of them of contemporary art. The optimisation of the museum as a form of show has been seen growing, beyond the exhibited collections, through the architectural factor. The show of museum architecture was already formed through the use of the self-same Louvre Palace following the French Revolution, a museum opened to all citizens. The National Gallery in London was also conceived as a focal point of visitors’ attraction, and as a demonstration of the British Empire power. The suggestive forms that Frank Lloyd Wright generated for the Guggenheim Museum in New York five decades ago have been reinforced with the impeccable architectural show articulated by Frank O. Gehry for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. Along these lines, we could make a collection of important anecdotes referring to specific cases like those offered by the Tate Modern in London, Macba in Barcelona, Gulbenkian in Lisbon, Moma in New York, Pompidou in Paris, etc. This is a geographic and architectural itinerary in which the spaces and volumes of the building compete in interest with the artistic work on display inside them. This curious behaviour of current customs acts as a catalyst among city visitors. Antoni Miró brings us this scene, captivated by its imagery, narrates his experiences through pictorial compositions in which either the architecture or the artist himself, or both, convey to us the present pleasure in the visitor’s behaviour who, in turn, become an interpreter of the narration.

Mercè Ibarz gives her opinion on these types of question, on the role that museums play within the current panorama. She believes that one of the new paths for the aforementioned process is the politicisation of museums, "the renovation of the political viewpoint through the museum of contemporary art" (Ibarz, 2003: p. 59). Ibarz comments on the close relationship between museums and the powers that exist, referring to an exhibition project guided by the director of the MACBA, Manuel Borja-Villei, entitled The People’s City, in which stories of life are interposed with images from the artistic panorama. It is through this model of initiatives that we can come to convince ourselves that the work which the media will never do can be articulated through museums and art. In some of his images, Antoni Miró appears using a photographic camera and pointing the lens at the spectator. It is in this flow of gazes where lies our greatest interest.

People’s Museum

For centuries the museum has been a pattern of solidification. Fortunately, for some years this reality has changed, such that the museum as an institution has weakened this concept of conservation and maintenance of collections, to become a space for communication with a vitality and a series of attractions keeping with the new cultural, political and media scene. Museums seek a new public, but above all, they try to connect with their visitors. The concern has shifted from the collections and pieces to the public. The uses and customs that had taken over museums have given a way to a new use of the institution which is much more permeable to the reality in which we live. In fact, the interest in public opinion is based on the reflection with respect to the visitors’ opinions, at whom the exhibition’s effort is aimed. Antoni Miró turns this new trend into a source of inspiration and takes to decidedly participating, as a visitor, in the splendid rollercoaster of the museum’s show.

We all feel attracted to the new museum policies. Furthermore, Antoni Miró participates with his brush, and through his creations, in the role of generator of pictorial snaps. Miró visits the museum and recreates it in his painting. His pictures then move on to the exhibition halls. This work has, in the end, a pedagogical side in the Miró series as a whole, since his reflection is plastic, pictorial, visual, but above all allows participation with respect to a new cultural movement.

The museum is one of the city’s most important institutions. In fact, the city and the museum become first class educational elements. Artistic education is not found in a classroom. There are no specialists who teach it in compulsory education. This is why the museum -and the city- attain a pedagogical quality, since they become the appropriate surroundings for the citizens to learn art (Huerta, 2004, 2005; Martínez, 2002). The role of the museum and the city in the education of citizens acquires its own importance, since it articulates a true educational space from outside the curricular sphere.

People’s quality of life is also to some extent dependent on their ability and control in administering their own education and leisure time. All through one’s life (we should not think that this is an obligation exclusively aimed at an under-aged public or schoolchildren), one will find a series of artistic and educational offers that one may either use as possibilities for pleasure or critical reflection, or let a series of such opportunities pass by, according to one’s interest and capacity. If we understand that a positive way to grow means increasing our background experience, taking on board new reasoning, then we will have to open up new opportunities for art, both through the media and the museum as an institution. Cultural facilities would thus, turn into useful places for citizens, and museums would be, without a doubt, the privileged element in this new educational way of planning. The museum could even be a meeting point with which in the future, new ideas, new focuses, possible perspectives for change will come. Citizens, both the ones who live in the city and the visitors, use museums for pleasure and to detect new orientations, in the broadest sense of the term. This means, moreover, giving the institution a more democratic importance, backing a new definition of the citizen.

In a suggestive definition drawn up by Trilla (1999: 24), we can find an analysis of the meanings and dimensions that a supposedly educational city might have. Trilla refers to three dimensions which we could define as follows: (a) the city as a container of education (learning in the city), (b) the city as an educational agent (learning from the city) and (c) the city itself as educational content (learning about the city). These three dimensions can serve to form a framework for the concept of the museum, and the city-museum too. That is to say, not only does the museum constitute a part of a broader educational city, but also ends up becoming a touch stone parallel to this reality, an invaluable space for truly getting to know the city. Antoni Miró, in his pictures, does in fact, paint this model of references, since he consciously follows the educational roles pointed out, as an arbiter. The painter drinks in the city to generate his work. And the painter, when he exhibits his work, takes part of the cultural framework that every city offers for cultural exchange. Once again, a challenge, taken up by the artist from Alcoy.

Olga Martínez (2003: 283) points out, in her essay the pedagogical alchemy established between the museum and the city, that when referring to the critical side and participation, it has been shown through pedagogy that teaching others is how we better learn. In other words, knowing how it is learned by communicating. We can see that Antoni Miró’s master class takes on board this responsibility: to learn and to teach learning as an effort of solidarity to communicate his ideas and impressions as an artist. The crossbreeding in Antoni Miró means continually crossing these barriers between which it is learned and offered, with which he again gives us a humble lesson in his artistic commitment.

Bites of the metropolis

The city does its utmost to show us its best side. The tangle of visual elements that attack us from the urban space in reality shows its interest in compiling the social, economic and cultural changes that occur ceaselessly deep inside it. Human movements express its peculiarities. But the city also harms us with noise and environmental pollution, while delighting us with its chiming advertising notices that in the end make up the very urban landscape. As if it were a child’s game, it offers its best screeches, with police, ambulance and fire engine sirens, traffic lights and signs that flood the surroundings’ visual references, with street fittings and printed adverts that exaggerate our receptive abilities and take them to extremes, with buildings of inconsiderate height that exalt in arrogance through their vertically and its consequent vertigo. Homes get mixed up with the uses that are made of them. We know that immigrant communities end up using any corner of a house as a room, since they live in conditions that are often unacceptable. And we also know that it will be precisely these groups of immigrants, with little means, who will suffer racist attacks from violent, organised groups. All of these events are the "movie" of the city, and while a classic such as West Side Story told us of some of these symptoms through songs, some recent proposals from directors such as Ken Loach in his tales with a social slant such as Raining Stones, or José Luís Guerin’s powerful En Construcción (Under Construction), encourage us to think that the languages of art can also be used to talk about brave analyses for the most varied of situations.

Antoni Miró’s works are situated along these lines of observation and following complaints. In his series he speaks of people who pulsate through the city scratching together an existence contrasting to the disproportionate wealth of the powerful; he speaks of the groups of workers who fight pacifically in the streets demonstrating to demand fairer working conditions, of women who suffer harassment in their helpless situations, of children who suffer abuse – most of which is committed by their closest family members. Of people who suffer in the city, but also of people who live out their lives through the city, and that transmit their image as an implicated part of the urban space’s processes. Antoni Miró collects the most heart-rending details of this latency and pours them on his canvasses with a meticulous ability to fit every minimal suspicion into its right container. This is the artist’s effort to narrate his vision to us, and his uneasiness. Thus, he shifts us towards the sphere of downfalls, an uncomfortable situation at the best of times, and in this way he puts us into a necessarily uneasy position which leads us towards other more hopeful ones where we are forced to make demands. Without losing heart or getting discouraged, Antoni Miró’s pictures infuse us with enough rage as to experience a healthy emotional discharge, on which we support ourselves to reach a most agreeable state of reflection.

In a city like Valencia the exaggerations too often hide the certainty of numerous imbalances. The use of the streets at certain times of the year for such publicised spectacles as “Las Fallas” or a wide variety of processions, together with the impact of light that invades the streets at nocturnal hours, are nothing but symptoms of excessive vanities, details that splendidly decorate the scanty results in terms of social equality. Behind these impressive blazes, the result of an ill “Mediterraneanness”, the city lives through the same internal getup as any southern European city; a land scape affected by old afflictions through which a glimmer of certain sparks, with their blinding light, hide the backwaters of a collection of much more shadowy zones.

Bibliographical references

- Benjamín, Walter (1982): L’obra d’art a l’època de la seua reproductibilitat tècnica. Barcelona. Edicions 62.

- Benjamín, Walter (2005): Libro de los pasajes. Madrid. Akal.

- Borja-Villel, Manuel [et alii] (1997): La ciutat de la gent. Barcelona. Fundació Antoni Tàpies.

- Efland, Arthur (2004): Arte y cognición. Barcelona. Octaedro.

- Gennari, Mario (1998): Semántica de la ciudad y educación. Pedagogía de la ciudad. Barcelona. Herder.

- Hooper-Greenhill, Eilean (1991): Museum and Gallery Education. Leicester. Leicester University Press.

- Hooper-Greenhill, Eilean (1998): Los museos y sus visitantes. Gijón. Trea.

- Huerta, Ricard (2004): Cultura Visual a Ontinyent. Ontinyent. Caixa Ontinyent.

- Huerta, Ricard (2005): «El museo tipográfico urbano», in De la Calle, R. i R. Huerta La mirada inquieta. Educación artística y museos. València. PUV (in the printing process).

- Ibarz, Mercé (2003): «La ferida i la cura. Sobre la foto i el museu», dins Transversal. Revista de cultura contemporània, núm. 22, Lleida, p. 56-61.

- Klein, Naoml (2002): No Logo. Barcelona. Paidós.

- Lynch, Kevin (2004): La imagen de la ciudad. Barcelona. Gustavo Gilí. 1st. ed. of The Image of the City in The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts), 1960.

- Marín, Enric i Tresserras, Joan Manuel (1994): Cultura de masses i postmodernitat. València. Tres i Quatre.

- Marshall, Richard D. (2002): Edward Ruscha: Made in Los Angeles. Madrid. MNCARS - Ministerio de Cultura.

- Martínez i Álvarez, Olga (2002): «Tres elements d’alquímia: pedagogia, ciutat i museu» dins Revista Catalana de Pedagogia, vol. I, p. 267-292.

- Satué, Enric (1984): Un museu al carrer. Lletres, imatges i textos dels rètols comercials a Catalunya. Barcelona. Diputació de Barcelona.

- Satué, Enric (2001): El paisatge comercial de la ciutat. Barcelona. Paidós.

- Trilla, J. (1999): «Un marc teòric: la idea de la ciutat educadora», in Ciutats que eduquen i que s’eduquen, Barcelona, Diputació de Barcelona, p. 11-51.