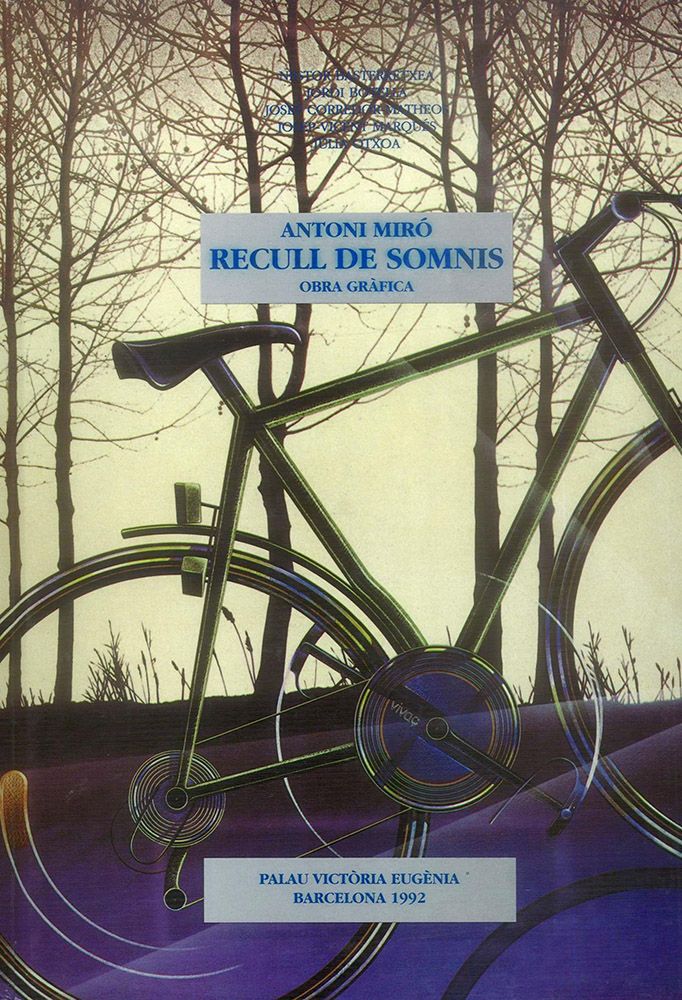

Vivace by Antoni Miró: The unveiling of a new series

Jordi Botella

I

It is indisputable that any artistic creation is driven by an impetus, an outburst, a push of the rudder that stirs up our existence and compels us to take certain actions. At times the shakeup that suddenly moves us causes an opposite reaction and curtails the impetus and then takes control of it. It is as if we were afraid to take a step forward, and we prefer to withdraw.

A mid this give and take, a work of art looks like a plaything in the hands of two children, one of which is axious to run off with it and the other is uneasy by dint of gazing at it.

These two types of artists remind one of what Julio Cortázar said about the various attitudes expressed by writers vis-a-vis the novel and the short story. Cortázar used a boxing metaphor to describe the first type, who would win by points, while the second type would win by knockout.

The first type, the “snail” creator, waits for creativity to arrive and in the end defeats the monster. The artist pesters the monster day and night, until he abandons the fight or surrenders to the artist who relentlessly strives to squeeze everything out of him.

The second type, the “snake” creator, on the other hand, and despite the fact that he is every bit as fickle as the snail, reduces the duration of the fight and, consequently, the adversary's agony. But, while the snail thoroughly gorges himself on the work of art, the snake creator, although he hits the bull's eye first, sometimes comes upon such treacherous beasts as the fox, who play dead and then slip away when the hunter is looking the other way.

Antoni Miró is one of the few painters able to fluctuate between a reflexive creation and a creation driven by immediate impact; that is, he alternates between the tenacity of the snail and the impact of the snake.

Throughout his career Antoni Miró has managed to combine both possibilities. He does so through an explicit “public service” urge expressed in the form of an accusation, ironic reflection on art or a commitment to the checkered history and the disquieting language of our country.

Along with other artists, Antoni Miró has managed to show that beauty is not irreconcilable with well-timed impertinence and that if culture is to reach the masses, it must be offered, not in the form of a school textbook, but as a source of pleasure, something to which everybody has a right.

II

This presentation of the series of paintings by Antoni Miró, entitled Vivace, goes out to all those artists who, at the twilight of this century, are enthusiastic about life, despite everything, of course. And despite the deceased, whom e carry on our shoulders, and despite those fools who fort us with modern conveniences and all the marvels typical of a nation of idiots. Despite all that, we still have one card up our sleeve, maybe because after seeing our gods and paradises vanish, the time has come to proclaim the State of Innocence.

Artists, devoid of any dogma, and, more important, the citizens, are confronted by creation and by life; their only baggage is their own language. In today's circumstances, in which alibis no longer work, creators can no longer hope to express, through the wink of an eye, a message that the creation itself fails to resolve. A rose does not need a sonnet in order to be more perfect.

Antoni Miró's series, Vivace, is an expression of this new attitude. Miró, a native of the city of Alcoy in Alicante, used to favour reflection over passion and sarcasm over spontaneity. But he has now returned to his roots, without losing the artistry he has gained from so many paintings. He has burnt his bridges and has emerged stronger than ever.

We are accustomed to his Cartesian view that he must exhaust a subject until its social, nationalistic or meta-artistic content is fully spent. And we are used to his expressiveness confined by his own references. In any event, Vivace is a bright spark in the work of Antoni Miró, in which we see an exteriorization by which he releases all the energy that used to be bound up by motives that used to run in circles, with the result that he returns to his point of departure: reality, rather than the work of art.

His previous work revolved around a series of concentric circles, like a dog chasing his tail. The viewer's gaze acted like a stone thrown into a pond. As regular as clockwork, the gaze triggered a whole chain of mechanisms that made sense thanks to the association of ideas that they aroused. Consequently, The Surrender of Breda by Velazquez is viewed as a humiliation of the Catalans by centralized Spanish authority and, in the Guernica painting, the dramatic figures are grouped above Espriu’s head in a fusion of the atrocious war and the desire to live peacefully, or, as one poet once said “eternally in peace and order, in work amid the difficult and deserved freedom”.

This effort at synthesis and concentration fulfilled the idea of interiorization, through which works of art remained subordinated to a critical posture vis-a-vis our artistic or political history. In the Vivace series, that revulsive to know that was more exp licit before is still there. But now it gives free rein to the gaze of others in such a way that, without forsaking the critical will that has always prevailed in the works of Antoni Miró, the content of the painting no longer has to refer to other motives, be they a product of culture or the imagination of the person beholding it. In the past, these motives gave rise to a vicious circle.

So we see that in this present day “total desire”, which is open and devoid of any prejudices, there is room for more than only strictly artistic or political reflections. In bringing to the fore the didactic side of his work, Antoni Miró does not turn his back on the commitment that has threaded through his entire career; quite to the contrary, he intensifies that commitment. Beyond the urgency of the earlier period, today there is a need to go further, to transcend immediate concerns and to shoot the moon, so to speak. As if to truly come to terms with the real world, you have to dive to the bottom, discover the limits and then return to the surface.

The commitment, then is no longer established a priori, nor is it subject to any particular slogan. Vivace, at great risk, enters a zone that is both cloud y and more tangible than all the previous series, and perhaps more coherent. But it is also more hermetic because it is subordinated to an earlier message.

The commitment will no longer affect only a segment, be it artistic, national or ideological, but rather a totality. It will be part of a free universe instead of being confined to a framework of complicity. The commitment will not necessitate a reflection on History, Culture or Politics because these three clumsy subjects, which are really only valid for the taxidermist, and which are as obscure as sacristy, do not reveal life as it really is. That, at the end of the day, is what a real commitment is all about.