Antoni Miró: a decade of «Pinteu Pintura»

Joan Àngel Blasco Carrascosa

«I have the right to be the way I am, even if it’s only for the fact that I was born that way. And this is the problem, if you’re trying to do the same thing».

Joan Fuster

It has been said. Antoni Miró has every right in the world to stand up for his singularity. It is a demand upon those who, like him, are conscious of the need to demand this personalizing differentiation for themselves. The search for the realization of the «ego» is that which has always been the main feature of the behaviour of this plastic artist since 1944, the year in which he came to life with the determined intention of becoming Antoni —or even better «Toni»— Miró. Since then, he has been forging a personality of his own conspicuous characteristics, the traits of one who should only be compared with himself. A man who has founded on ethics the basic structure of his life’s aspirations; who has firmly maintained faith in certain axiomatic principles; who has already left behind him a plentiful wake of artistic inventions, whilst he continues to be involved, with the daily dedications of an ascetic, in the fashioning of his aesthetic work; who looks inwardly to himself with the same self-demanding attitude with which his critical eye accuses the foolishness of contemporary society; who with a radical non-conformist attitude gives whole-hearted support to involvement and solidarity; who has set himself up, using his art, as a champion of more than a few just causes, amongst which stands out, like a crest, that of liberty... This Antoni Miró, who is obsessed with order and method, who says a lot —«el que he de dir ho dic amb les meues obres»— (N.T. What I have to say I say with my works of art) - whilst his shyness means he speaks little and listens a lot, has one idea very clear: getting to people - and here we have his strong desire to communicate through his artistic works.

Alcoy

«If like the child who knows to walk along his own street...».

Ausiàs March

In fact, Antoni Miró knows well how to walk along his own streets, the streets of «his» Alcoy. One can only love which one truly knows..., and one can only know which one has experienced with intensity. Antoni Miró has always lived in Alcoy, and if the affirmation of Jean-Paul Sartre that everything originates in childhood is true, we will agree with him that the knowledge —and the love— of our painter for his place of birth, are to be found basically in these early experiences, thereafter followed by his early artistic activity.

In this Alcoy of steep streets which trace from the Islamic culture the starting point of a trajectory and a vocation set on the path to follow the call of art. The Alcoy of crowded houses and high bridges, palpitates, together with its inhabitants, with the «trons» of Saint Jordi, to the picturesque rhythm of the «filaes» of «moros» and «cristians»; the laborious industrial Alcoy of the looms, the paper mills and the printing presses, of a very concentrated social history; the Alcoy of artistic vein which nourishes painters born there, such as Sala, Casanova, Gisbert or Canbrera; that Alcoy of the region Alcoià, surrounded by the Sierras of Mariola and Carrasqueta, and divided by the waters of the rivers Serpis, Barxell and Molinar, which were to have the effect of forging in Antoni Miró a more and more refined idea of his town, his county, and of his Country...

In this Alcoy, the human and artistic personality of Antoni Miró is hatched. He is born into a family of metal workers. His father is a smith and his mother a seamstress. The prematurity of his skills at drawing are soon well known in the neighbourhood. Our incipient artist, sickly and silent, helps his father in the small carriage repair workshop, as his brother does Vincent. With almost no time to play, he practises hiding what later would become an authentic obsession: drawing.

Vocation

«Manage to be who you are».

Pindaro

It could be said that someone has presented himself at the door of the artistic sensibility of Antoni Miró, and calls insistently, with urgency. It is this vocation, an early call, that arrives speedily to seduce him. Our painter is ready; it would seem that he was awaiting this magnetizing voice. He has heard the order with the resoluteness granted by every day’s effort—which, at the same time, is an entreaty— of the Greek poet. He wishes to become the person he has inside, to develop his innate possibilities. And he knows that the best instrument at his disposition is none other than his education through work.

He draws and paints «through his own driving force». He does not attend any centre of artistic education. Until after his sixteenth birthday he does not receive any instruction or regulation in aesthetics. Drawing and painting he gets to know Vicent Moya, a local artist who orientates him towards the practice of still lives, landscapes and portraits. But academicism does not fit in with Antoni Miró’s free will. He wishes to attain his own impulse, and says an emphatic “no” to routine in order to take the path of investigation. He investigates with novelty materials shunning traditional ones, trying to connect in this way with contemporary industrial society. His intention is «un art amb intenció de servei humà» (N.T. «An art intended to serve the human being») and to this end, he lends himself most decidedly.

The inflamed artistic activist displayed by Antoni Miró in Alcoiart cannot be understood without taking as a premise the haste in his vocation. Fifty-five exhibitions in the period 1965-1972, constitute a proud display of his artistic promotion. His colleagues of the same group, Sento Masià and Miquel Mataix, do not dispute the leadership with him in this adventure which, spreading away from Alcoy, was to reach lands and peoples of France, England and Italy. Even without there being a common aesthetic project, «Alcoiart», with its search for artistic integration which is not solely pictorial, this will remain as testimony of an energetic undertaking, of a passionate vocation.

The compromise

«No, painting was not made to decorate apartments. It is an instrument of an offensive and defensive war against the enemy».

Picasso

Let us go through the living environment of Antoni Miró until he took on the vigour of youth; born into a family of workers, in a city so full of historical tensions as Alcoy is, and in a País Valencià whose national identity had been progressively weakened throughout the period of obscurantism of Franco. The awakening of conscience - both that of class and the national was to occur at the same instance together with the first sparks of his plastic poetry. His interpretation of life and history was to progressively illumine his sense of reality leading to his taking a stance with regard to the world: the compromise.

The artistic stage of Antoni Miró which links a coherently evolving transit from Expressionism to «social Neofigurativism» can already be shown to have a strong ideological content, and his series of pictures: «La Fam» (Hunger), «Biafra», «Vietnam», «Mort» (Death), «Realitats» (Realities), «L’home» (Man), «Amèrica Negra» (Black America)..., bring to evidence the preoccupation of the artist for social problems. So many latent problems, from injustice through the lack of solidarity to oppression are to occupy the centre of interest of his artistic message. Antoni Miró himself has told us: «I reflect the general problems of these times», and such a statement displays at the same time inconformity and a promethean aspiration for a just and free world.

This is the key to the poetics of Miró: knowing how to connect ethics and aesthetics by means of a dialectic comprehension of art. He is aware that the time which has fallen to him in which to live is dominated by the cult to imagery - so often taken to the level of myth. He thus, uses the procedure of forming models of plastic art, using imagery of great impact, which offer a humanizing alternative. This means, necessarily, abandoning any temptation at an art of a neutral, frivolous or unimportant nature. On the other hand, with an imagery full of meaning, uncomfortable, disquieting, he attempts a positive art, with a great informative potential, of real communicative efficiency. This is the compromise of Antoni Miró, after his having become conscious of reality: the defence and exultation of human rights.

The accusation

«I paint precisely what I don’t like».

Antoni Miró

The themes chosen for the making of —and with which to make— art, also define the painter. Moreover, they show the motivation and intentions which tell us of the factotum of these inventions. With Antoni Miró, his themes consist of a reflection of all dear to him, but seen inversely. He, himself, decided to paint, right back at his beginnings, which disturbed, disgusted, or even repulsed him. He took a leaning for art which accuses, using which has been called «conscience-bearing painting». More than merely representing beautifying or idyllic, peaceful or restful subjects, he inclined towards the direct and impressive message, often crude, converted into a radical allegation against historical and present-day irrationalities.

Thus, enter into his sharp viewpoint: the disasters of war; the unleashed passions which originate violence; the disgraceful blemishes of poverty, both individual and collective; the aberrations of racism; the upheavals of mental derangement; the urgency of social emancipation; the incipient instability of human alienation; the maquiavelic danger in those who manipulate; the paranoias and schizophrenia of dictators; the longings for cultural and national independence; the barbarity or the capitalist aggressor; the immorality of the colonial imperialist... Sometimes with sarcasm and sometimes using satire, always using the method of an accusing report, the art of Antoni Miró —so necessary, still— attempts, by shocking, to liberate: the catharsis of the observer of his works. This aim was proclaimed, previously, by Georges Braque: «L’art est fait pour inquiéter» (N.T. Art is supposed to disturb); certainly, to disturb, to needle such cosy comfort...

It is for this, that it has been said —with reason— that the art of Antoni Miró is political art, interwoven with the thread of criticism, bearing shocking meanings of a nasty but salutary nature... But is it the case that there is still so much to sweep clean? Could hypocrisy have blunted the lance in which the paintbrush of Antoni Miró was to be converted? Are there no arguments of weight to postpone —until when we do not know— art of innocence and candour?

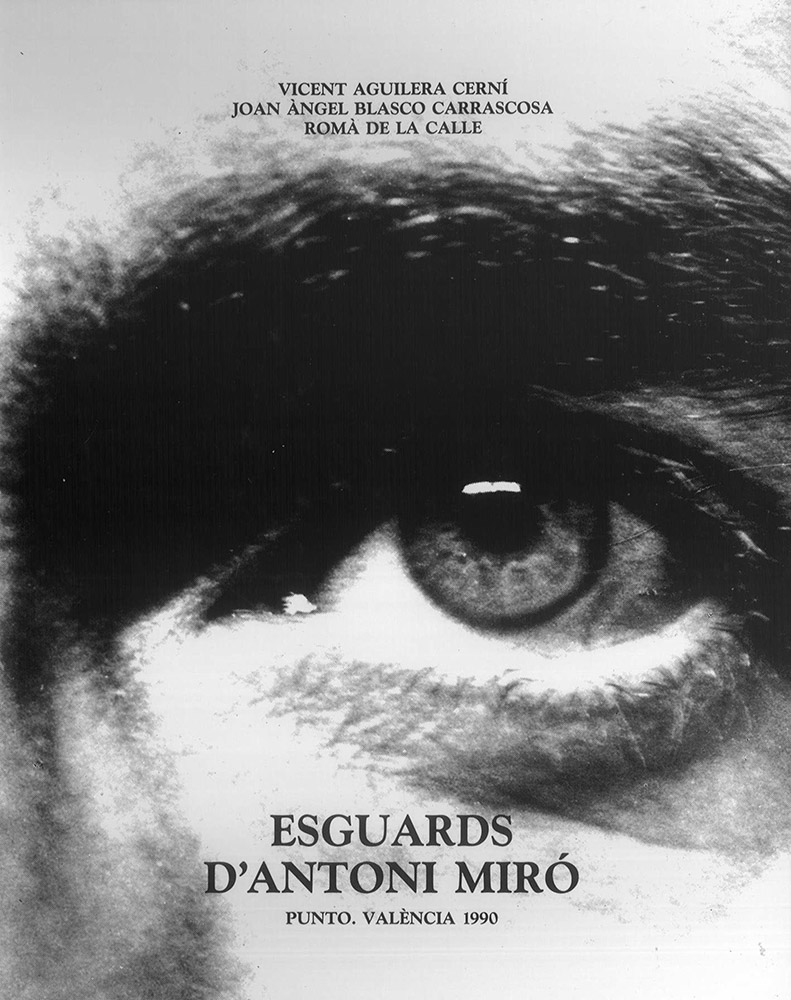

Looking

«The only critical act is my action of seeing».

Oldenburg

More than «seeing», Antoni Miró exercises «looking». There is then in the basis of his actions, a strong will and a searching, a constant interrogation. His look is centered in present-day life and in the originating causes of the realities of nowadays. For this reason, exactly a decade ago, in 1980 he started an adventure in plastic arts, as personal as it was involved; bringing about a new reading of the history of painting, choosing authors of significance and themes connected with the intentions of his art. This is the basis of his «Paint-Painting»: Historic milestones of the past of art revisited through the prism of the use of new expression resources, always aiming to stimulate the spectator’s perception.

Such a look to the past, in order to make the present clear and to enlighten the future, has to be created in a way that is neither ambiguous nor indeterminate, but with informative clarity. This is the reason for his choice of a figurative iconography, which, given its critical nature, has been clichéd as «social realism». In this sense, his plastic art work is included in the realistic trends of international painting amongst other Valencians of great artistic merit, such as Genovés, the Equipo Crónica, the Equipo Realidad and Anzo. But such concomitant creation, emanating, without a doubt from the heat of Rupturism from a deeply ideological stamp in the sixties of the Spain of Franco, do not permit all these plastic artists to be included in one all-englobing poetry without nuances. Rather, each of them, with their idiosyncratic interpretation of reality, crystallized into very particular styles.

This is the case of Antoni Miró, who, intelligently manipulating the imagery of the industrial-technological society’s propaganda, as it passed through the formal sieve of a non-American Pop-Art, or an Optical-Art –or even Cinetical-Art–, elaborately synthesized and economically expressed. Thus, this «style» of Miró is created, whose definition, or the keys to such, can be traced not only to his pictures, drawings and etchings, but to the birth of other types and processes - sculpture, metalgraphics, pottery, murals, mobiles, etc., give irrefutables evidence of the iconic condensation which his look has given rise to. A look which has now been translated into aesthetic objects, also made for looking at...

Irony

«Everywhere, after various centuries of triumphal subjectivity, what awaits us these days is the irony of the object».

Baudrillard

The difference between the sixties and the eighties is the measure of that difference between homo politicus and homo psicologicus. The substitution of utopias attempting transformation for the intimate self-withdrawal of a hedonist and individualist nature, sketches the profile of these new times bringing —obviously— different sensitivities. Antoni Miró is well acquainted with these sociological and aesthetical ups and downs, which are indicators of differentiated and differentiating cultured patterns, and would appear to accept Hegel’s phrase: «What has to be expressed is such contained in a given situation». Moreover, without abruptness, taking pride in finesse, a growing keenness of an ironic note can be noticed in his work. Progressively, his images, chosen from the history of painting or from the mass media, are exchanged for new pictorial images of a greater polysemic tone, keeping with the rate at which, with genius, the bar of the metaphoric or metonymic wisdom is raised. The painter’s look is sent back to us —now— passed the sieve of the conniving look of the characters painted. It is then a different strategy that continues to call us —as Antoni Miró often does—, without losing a grain of causticity or mordacity and gaining in sophisticated originality. In this staring game, the selected iconographic legacy of universal history is decontextualized and recontextualized. Recurring to the mentioning and comparing by means of the quotation or reference, it implies a subtlety of connections that the artist has to exploit to the maximum. As the irony of the object is observing us, let us use this weapon of Postmodernism —Antoni Miró says— in order to filter our thoughts... This thought which, translated into images, will provoke in itself, with the intelligent staring game of others, new thoughts and other images...

Contrast

«As beautiful as the casual encounter, upon a dissecting table, of a sewing-machine and an umbrella».

Lautréamont

No, it is not an attempt to confuse the reader. The well-known phrase that we have placed as an epigraph, is not attempting to point to an aesthetic wavelength of our painter held in common with the poetry of surrealism. It does, on the other hand, attempt to introduce us into this «realm» of contrast, basic in the artistic conception of the works of Antoni Miró. This contrived shock, as a reactivator to so much visual dullness, if not to a certain assumed visual apathy, is to be found in the marrow of the conceptual background of «Paint-Painting». At times, juxtaposing personalities, other times, superimposing objects, or alternatively isolating fragments; the author of these plastic inventions gives rise to a game in the spectator, optional in its device. The composed strategies thought up by Antoni Miró, which affect both the morphology and the syntax of the image, are varied; sometimes, with the reflection, they stem from an image based on himself, he is applying the «principle of the mirror»; in others, enlarging, reducing or lengthening, by means of deformations, objects or people, he brings us new «readings»; and, finally, recurring to superimposition, parallelism, coercion or inclusion, he goes on searching these adopted images, which in the first place, constituted the central leit motiv of the composition.

We refer to the iconographic repertory of Antoni Miró in «Paint - Painting» in order to confirm either conjectures or affirmations; the artists selected are fundamental names of undisputable universal ranking (Hieronimous Bosch, Dürer, Velázquez, Tiziano, Goya, Gaudí, Picasso, Bacon, De Chirico, Mondrian, Miró, Dali, Magritte, Adami, etc.). At the same time, the chosen works of these paradigmatic artists are famous due to their popularity, given their multiple circulation: «Las meninas», «Los borrachos», «La fragua de Vulcano», «Inocencio X», «El Conde Duque de Olivares», «Carlos V en Mülberg», «Carlos III», «Autorretrato de Goya», «La Duquesa de Alba», «El albañil herido», «La laitiére de Bordeaux», «Les Demoiselles d’Avignon», «Guernica», etc. There is no doubt that the simultaneous reproduction of iconographies of different authors and styles would produce the well-known contraction, stimulating the retina of whoever observes the work! This play of opposites, which underlines differences and disconformities, induces one to perceptive patterns and elements of cognition distinct to the usual. A new beauty emerges from such mixtures, from such studied hybrids. The shock-effect is achieved, and thus the attention of the anonymous «onlooker» is gained.

Liberty

«One paints because one wants to be free».

Duchamp

I do not think I would be saying an untruth if I say that Antoni Miró paints to be free..., and so that we might all be free. I would even dare to state that for him, freedom is more than mere spontaneity or the well-known margin of irresolution. On the contrary, it consists more of the realization of a necessity; liberation «from» something or «to attain» something..., and not just individual —I repeat— but collective.

This is why Antoni —«Toni»— Miró paints. It is not a simple question of «no coercion» or «no restriction», even though these are most important. He goes further than that. He believes that Man «forms himself»; «within» liberty... and that, this possibility of choice and self-determination should be also amplified to the different peoples. Now do we understand better his militant nationalism, within the ambit of Catalan culture, as the only possible way to internationalism?

Antoni Miró —a romantic, a painter, a dreamer of liberties firmly based in social justice— needs the isolation which Leonardo da Vinci demanded: «Be alone and you’re all your own!». And this distance which solitude permits and the independence required for creation, he has found —of course! Near to «his» Alcoy— at Mas de Sopalmo. There, our painter lives and works, sufficiently isolated from the noises of this world to be able to bind himself to the daily task of plastic experimentation (as Vicent Andres Estellés said; «Fill meu, tothom que crea està sol». N.T. My dear son, everyone who creates is alone), and near enough to the society and historical moment of his time to be able to go on accusing and being ironic. In Sopalmo, a place where the neat and tidy are the rule, a faithful reflection of the solitary work of this tireless and steadfast artist; a refuge in which friendship —always the fruit of free choice— is cultivated in long conversations, to the detriment of sleep; the atmosphere of the home, together with Sofia and Ausiàs...

I have read in The compromise in literature and art, of Bertholt Brecht, that «realistic artists describe the contradictions between men and their relationships between each other, and expose the relationships into which they develop». It may occur that in the not too distant future, you may have the chance to meet «Toni» Miró personally, in Sopalmo, concerning these or other questions. You will probably find him —cerebral as he is— piling exhaustively through documents concerning a new series of themes, or putting the finishing touches to his most recent creation. There is no escaping from it. He has dedicated himself to painting in order to be free..., and —allow me to repeat it— in order that we might all be free...