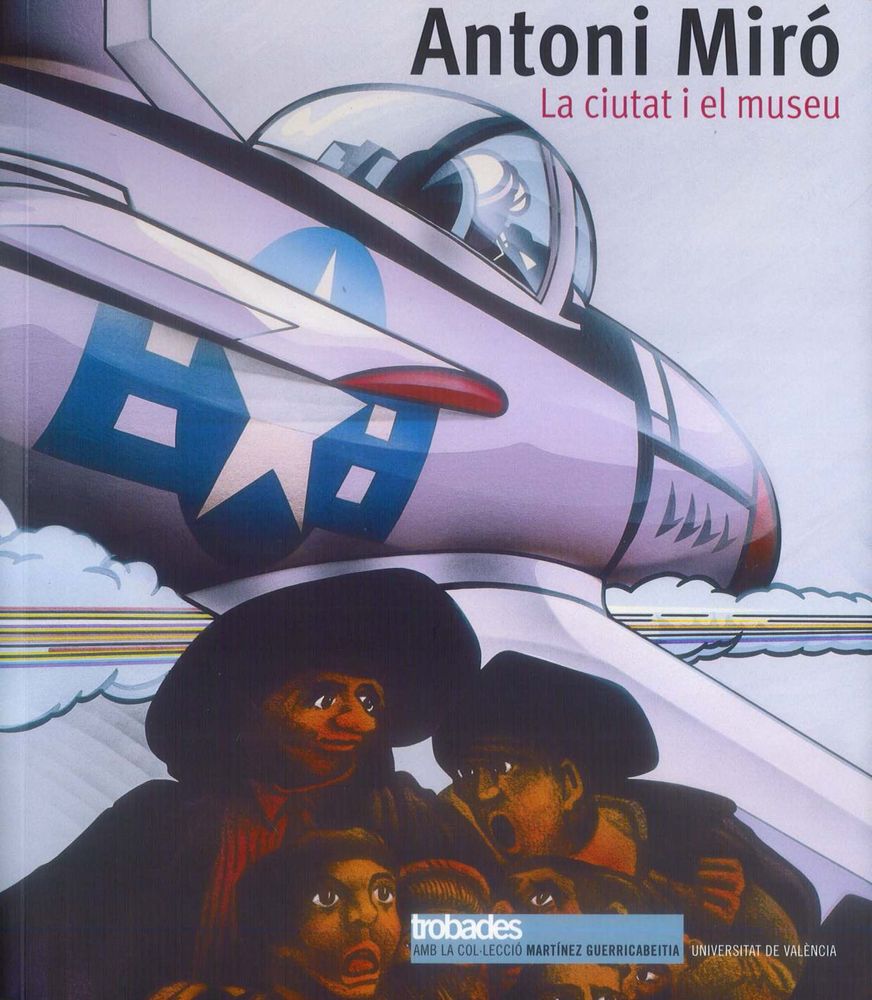

The restless and allegorical eye of Antoni Miró

Floriano di Santi

I.

Modern culture is inhabited by worry as the emblem of modernity: writing about the body, about pathos and pain. If we think about the divided me, a well-known essay by Emmanuel Lévinas, Trascendencia y mal, comes to mind. This talks of the putrefaction of death as a disintegration of an identity that alters itself. Even the face, which is in the background of Lévinas’ philosophy, the face in which one recognises another and one’s responsibility towards the other, “becomes a mask”.The mask of suffering and loneliness is, however, a way of life, perhaps unreal, which covers the desert of emptiness, of isolation and sadness. This is what Ortega y Gasset had found in Don Quixote, in his “elongated frame”, “hunched like a question mark”. Indeed, this Cervantine mask could be defined as the enigma of impotence. He rushes at the giants, but the giants are not giants and, therefore, against them he can do nothing. A similar impotence makes the world àpeiron, which does not mean “infinite” in the spatial or geometric sense. It is rather a definition without confines or limits: a place -writes Leopardi in Zibaldone- which is improbable, that “cannot exist”, in which we move with no guarantee of arrival at any finishing line. It is inside us, in our anxiety and dissatisfaction pushing us to deny the belief that the world we are in is the only world possible.

Among the greatest of the 20th century in the literary universe, we find Pessoa’s desasosiego (uneasiness), a souffrance (suffering) that indicates a symbolic existential via crucis marked out by the season of decline on the threshold of nothingness. Is this not the place in which we see neither figures nor landscapes, that frightens us because in this lack of sight we are not at all afraid of becoming blind in the same fashion as an immense whiteness that dazzles us? In Metamorphosis, Kafka explored the vertiginous blindness of that which is not human: its protagonist, Gregor Samsa, wakes up in the morning after restless dreams transformed into a terrible insect. His voice moans at first until it cracks and becomes no longer a voice. After that, his eyes can no longer even distinguish the wall in front of his window, overlooking a narrow street. Samsa then enters into the nonhuman stage: after having gone along a narrow street, no wider than the space of his feet, trapped by a “sea-sickness on dry land”. He has invaded the other, the absurd evil, with no point of view of the abyss. And, how could he, if evil is inconceivable and if the only image that we are given is that of the horror vacui?

The angel of the night has a thousand eyes. Goya descended into the shadows and described the dense darkness of the restlessness soul. The Spanish maestro’s eyes dimmed little by little as the tragic event of the Quinta del sordo closed in, hanging onto the last glimmer, perhaps to discover the other beyond the nothingness. Who after him has drawn up these confines? Van Gogh, who in Wheatfield with crows painted his own eyes blinded by the flying birds in the unsettled sky; a certain violet flesh in the Soutine’s pulverisation of colours, or the tearing to pieces in Bacon’s portraits in which corporeality and flesh always carry the stigma of death.

The creative production of Antoni Miró is also measured by this mute Stimmung. This expresses -in lucid linguistic poetry- the conflictive co-presence of two anti-ethical forces that push in opposing directions: the severe eye of the meditatio mortis in the ab aeterno perspective of past masters like Velázquez, Goya, Picasso, and Juan Miró, It also disapproves of artistic activity as vain acrobatics of sensitive and ephemeral things. On the other hand, the very human, almost hypnotic gaze of the painter dragged, in spite of himself into a kind of static trance, into the unstoppable metamorphosis of “writing” through images. Here, we are following the inverted route that Paul Valéry called l’état d’attente, in other words, the state of waiting that the poet seeks and desires, and which precedes his becoming “another” in writing. Antoni Miró still lives disconcertedly through the conflict of becoming another through language; he shows us this conquest which is natural for the subjectivity of contemporaneousness, as an impulse that drags him out of himself, makes him a defector under suspicion in a different territory, that of the possibilities of the poetic fictio. In his work, he outlines a double-browed face of Jano, on one side, still the man of the past watchful of the omnivorous pillage of ancient knowledge. On the other, the man of modern times who not only acquires the erudite datum with incessant philological meticulousness, but also turns it into a hieroglyph of the soul, a symbolic piece of his personal history and a cause for reflection about history and the society of collective culture.

II.

Miró’s first works of some interest are from the seventies. His previous paintings -influenced by the academic koine of Vicent Moya- are strange, though they are interesting for the sake of documenting a resolute choice precisely because the artist from Alcoy discerns and does not simply make a careless veto, not even of experiences which he realises are not crucial. This seems to me to be a humility with which Miró immerses himself in the lesson of the cultural environment -in primis the artistic movements of El Paso, with Rafael Canogar, Antonio Saura, Manolo Miralles and Luis Feito, and of Equipo 57, with Pablo Serrano, Agustín Ibarrola, Nestor Basterretxea, Ángel and José Duarte-, he analyses his limits and values, performing- a significant fact. It is as if one is waiting for a metaphorical-ideological attempt, which the future work will reveal, to grow in the maturity that only time, through the vivid use of means, allows. And so, in so much as what it is and what it has in any given moment of the experience, it is used so that something of the creative impetus is announced in this moderation of expression which rigorously reveals contempt for any suggestion of language.

El bevedor and Bodegó amb meló are from 1960: in them, as an internal light on plastic abandoned volumes, the composure of shapes wraps itself up -as in another oil painting of the same year which represents a plate with four apples- following Cézanne. Unlike other artists of his generation, who use the suggestions of the great master from Aix-en-Provence, first coagulating his tensions in the archaic plasticity of the “Bathers”, to then arrive at modern, essential landscape painting, Miró comes down to the centre of structural modes in the way of Cézanne, repairing their essential luminous geometries: the germinal force of these plastic nuclei on which such a wealth of image is then organised. It is as if this young artist is interested in the initial moment, the genesis, of Cezanne’s image, the tension borne out of the discovery of the cause, and out of which comes the autonomous destruction of shape. Something similar appears in the first Canogar, in the splendid Paisaje de Toledo 1951, where the structural nucleus of trees appears to be centred on the tension of the hill’s growth behind the house and the enlargement of the image in the density of the brushstrokes that melt together in this store of emotion which restrains all possible development of form.

It is with an aerial view that we come back to the painting of that time, Paisatge d’Alcoi (1962), where houses and mountains hang; but it is a different eye that now observes the lights and reflections of that horizon, and it is a racing pulse of a different kind that now guides the brush. Nothing remains, in this work and less so in Fàbriques two years later, of the tonal distillation deposited in the very first works. That search for atmospheric values that bathed the palette and diluted the colours of the fruit and the portraits has disappeared; nothing remains of the progressive and slow rhythm of the construction; they are, however, fast and discordant gestures, unexpected interruptions of the brush’s race and sudden signs of disdain that reveal anywhere the rise of the stamp of reds, oranges, blues and yellows, substituting the humid greenish-blues, the tender fleshy pinks, the subtly varied earthy colours, and the lovingly stroked mauves.

The vision of the landscape releases a kind of drunkenness and warms it up in the form of croma resentment, amid fauvist and expressionist echoes, in such a way that the little Cézannian opening, in its first adoption, ends up becoming that wash of colour, more to rip out the spatial structures of the representation than to weave it together; to pull apart more than to connect one plastic plane to another, and finally to testify how the models of reference are situated on a different cultural horizon more implicated in examples of Monaco’s expressionism than those taken from the repêchage (recapturing) of French post-impressionism. Various landscapes and a small group of feminine nudes, scattered between 1964 and 1968, mark the determined departure point of Miró and the point where he overcomes his studies. The motif of the “cavern” -as a result of the writings of Leonardo- is felt like a metaphor from the maternal lap, and thus as a source of life, while the landscape motif joins the image of the past which, through an intermittent style, inside life, and through light, is transformed into the present.

Analogously, the motif of the “lump of material” is developed from the “foetus”, in the womb of the universe: a “foetus” that, recuperating the capacity to situate itself as a timeless event, re-proposes itself like a present megalithic projection. When, in Verges (1967) and Faç d’abril, Dover 1967, the polychromatic thickness is transformed into an accumulation of hieroglyphs, in the few essential lines, or in the magma-like spasm of a cosmic “landscape”, we sense that the “a-historical” trend of peeping poiesis becomes authentic “history” of our “existence”. The rough, cinerary, alarmed tache (stain), interpreted as a long or profound cry, like a precipice into which one can throw the enigmas of one’s own existence, becomes the most authentic information about which Miró wants to express with relation to a “before” and an “after”. In this way the artist states that the arrhythmia of his expression is determined by the continuous and unsurpassable difficulty to communicate and institute a relation of freedom between man and world; while he captures the disconcerting openings of Fautrier, Wols, Jorn and Tàpies, he feels something like Inferiority of spirit and the physicalness of things: the superimposition, or better still, the complete fusion of these two complex and only apparently contradictory realities, gives life to his filtered material apotheosis.

Miró’s immersion in the poetic side of art autre is complete and absolute, and untangles the mess of perception and iconographic signs, feeding on a material of smoke and an extremely light asthenic ash, liable to be spoilt by a simple pressure, but criss-crossed in the most secret of its nooks by fleeting flashes that create -in the words of Bachelard in La poétique de la rêverie (Poetry of dreams) - subterranean correspondences between what exists and what is imagined. His rarefied informality, reiterated movement of contractions and expansions, presents itself as a Joyce-like psychic continuum, like a diary that possesses and controls the sedimentation and thickness of our perception, like the wakened consciousness of a man on progressively losing all possibility of regulating past history and the upcoming future crisis verifiable only in the great melting pot of the existential search. Ambiguity, provisional certainties, the metaphysics of silence and dissipated images solidify in a chromatic paste, made of crepitation of profound tensions that seem to lead us to a feeling of longed-for freedom.

However, little by little, within this memory-space, deteriorated images are insinuated, discordant lacerations; a sign dangerously setting itself off begins to speak in first person, fills itself with feelings and becomes a “confession” of repression. Nevertheless, we cannot speak of automatic language, although the artist shortly invents his expressive means and their forms, and as these get stronger, his conscious judgement controls his expressiveness according to the concept-idea. It is the post-reporting moment of Vietnam I (1968), of Biafra 4 and of A Che Guevara (1970); testimonies, subtle and penetrating accusations that, in turn, Miró puts against the most painful facts of our dramatic second post-war. They are pictures whose gesture, and thus, their sign, symptom of suffering and as a vent for fear, tend to infiltrate in the material like conductors of current and worry, to expand in the mystery of an image violently projected forward to communicate pulsations recognisable in a Freudian light.

III.

Since the beginning of the first half of the seventies, some vital currents of “painting of the gaze” have been active. Due to their imaginative and figurative power, they move towards a structural-genetic reconstruction of artistic means and forms. This is about tendencies that, hyperrealist paintings use in city for advertising anti-ethically and alternatively American myth of objects and consumerism, give an anti-mythical image of class conflicts and introduce the experience of the plastic neo-avant-vangardists into the global experience of Marxist theory and practice. Such authors, of different philosophical/aesthetic types and education, have little to do with the eclecticism of Nouvelle figuration and Mec-art that elsewhere, in Italy and Spain, still divert many young artists from the truth. This is not because of what the bourgeois involution provokes in the latter a separation from the ruling class and its openly opposed attitude, such that the awareness of the crisis, loneliness and desperation of modern man become the big topics with which artists of all nations and some vanguard movements get to know about alienation of contemporary society and denounce its absurdity and cruelty, but above all, because it is necessary to distinguish as much yesterday as today, between the artistic forms that aim at a new art or prepare for the entry of signes originales in the space of the image and the action. Forms and signs of a humanist culture of the city, and those that aim for the progressive destruction of art.

Lucien Goldmann spoke of alienation, or better still of treating people like objects, in a fortunate study about Robbe-Grillet, referring to the Marxist notion that denounces the industrial/capitalist society’s tendency to transform man into a “thing”, into an object. In the methods of the École du regard, the French critic, who claims to be a disciple of the first Lukács -that is to say, the one who was still Weberian-, saw a kind of “triumph of the object”, a total aggression by the object on the subject. This is why it is necessary, for all those who make painting and sculpture ideologically, who make environment art and happening, to underline that bourgeois power manipulates culture precisely with the intention of making a fair historical formulation of the relation between art and society impossible. Never as in the second half of the twentieth century has it been so clear that the Marxist theory of a bourgeois development clearly aimed at the destruction of art was not a utopia, but a precise scientific hypothesis.

In various places we have heard different voices that proclaimed the death of “realistic art”, objective, as a “potentially tautological” experience. But seeing it in essentially ideological terms, is a false modus of reducing the meaning and reaching of its specific intervention. Perhaps, also of thinking ambiguously about the Gramscian “cultural hegemony of the working class”, spiritually poor instead of rich in the imagination of existence. This is what I believe, and the vision of the works of the four artists of Gruppo Denunzia reinforces my conviction: only with culture as a basis, it is possible to be inside life, to orient oneself and move life and art forward like revolutionaries. Indeed, for the painters Eugenio Comincini, Antoni Miró, Julián Pacheco and Bruno Rinaldi, and the critic Floriano De Santi, the immediate aim is the linguistic/communicative/semantic execution of their works. But the essential aim is to use this work as one of the possible ways of conserving, understanding, and giving shape to life.

In its search, painting is not an end in itself, but it also has a value for its educational and ethical content: it is a mode of existence and history. For the authors it is one of the ways (not the only one) of giving order and rhythm (with work) to one’s own daily experience, without abandoning the continuous infinity of the impressions momentanées (momentary impressions). Not avoiding them, or their reality, but leaving in due course the political mark of artistic reproduction of social continuity. It is a cultural duration that looks to take the image right up to the culmination of the analysis carried out with the Picassian “anatomy lesson” of a masterpiece like Guernica (an idea already performed, on the other hand, by didascalian politicians like Otto Dix, George Grosz and other Germans of the Neue Sachlichkeit, and also by the post-revolutionary Russian “Magic realism” and by the Anglo-American social-environmental movement of the twenties). Gruppo Denunzia was born, then, in 1972 in Brescia with the intention of considering a certain heavily significant situation (historical but modern) more closely: the existence of man as a being and a figure in current society, his hopes and desperate will to survive the crushing anonymity that solitude and crisis produce, the direct roots of rebellion and violence.

It is from here that this air of discontent descends, or at least this aspiration to cling on to that “human sense” of very rich real needs about which Giacometti also wrote: “For me reality is worth more than painting. Man is worth more than painting. The history of painting is the history of changes in the ways of seeing reality. And with respect to reality, I must make clear that, in my opinion, the distinction between Interior and Exterior reality is purely didascalian. Reality is a network of relations at all levels. A figuration which contents itself with being the instrument of useful knowledge to pull out alienation, would be tout court anachronistically, although it is already a way of becoming aware of reality and attempting to get out, to be rescued. However, the pictorial conquest of Pacheco, Comencini, Rinaldi y Miró does not seek abstract urban liberations from alienated forms in the urban iconosphere. It learns to understand in order to fight to transform the consumer commercialisation of capitalist power, which has so impoverished the man of “social objects” and human habitat that terrestrial space -and not only environmentally- is always about to become a dead planet.

“The images that appear in these artists’ pictures,” Mario de Micheli pointed out with critical sharpness, “are presented with different stylistic and expressive characters: they are drastic and dramatic images in Miró; narrative and almost chronic in Rinaldi; ironically pathetic in Comencini; and bitter, grotesque and sarcastic in Pacheco. But in any case, they are images for and against. Against the offence to the integrity of man and for the affirmation of his liberty (...) Now, in Italy and anywhere in Europe, the new artistic generation has shown that they know how to work in a direction that is not only wandering, hermetic and elitist one of the last experimentalisms. The reconversion towards the objective image is one of the most explicit signs, in spite of many mistakes which abound around, of a general trend which only four or five years ago seemed absurd to hypothesise about. Miró, Rinaldi, Pacheco and Comencini, in their own way, belong to this trend.”

IV.

In that season of Gruppo Denunzia, and after effectively closing his experience with Grup Alcoiart, Antoni Miró has not only been an artist of “manifest ethical drive” -as Ernest Contrares has defined him-, nor a simple painter of men, objects and places, but the maker of reports about violence, with a “reality of snap shots” constructed through a long gaze, a frozen stare, and with an almost photographic execution that seems to petrify the very analytical and cognitive process of racism, of squalid and triumphant misery in the field sand in the coloured ghettos, of solitude and social uprooting. In addition to this, he has been one of the Europe artists who have prepared “the space of the image” for the acquisition of other values beyond those already known, with the conviction that there could still be a présence déterminée for Spanish painting, along with the visionary/figurative movements of Valencia, Equipo Crónica and Equipo Realidad (in which culturally committed artists like Rafael Solbes, Manuel Valdés, Jorge Ballester, Juan Cardells,participated, and writers such as Aguilera Cerní, Tomás Llorens and Marin Viadel).

Miró’s works from the seventies -from the paintings to the sculptures and drawings- always have in them the same idea of violence: it is an obsessive and reiterative motif, a parameter, a “réfringent mirror” in which one recognises the effort to recompose the apparent chaos in historical terms. With a specific and dialectic opening, the unreachable distances, the now unclassifiable signs that escape a human logic which a blindly conservative ruling class, meanly hypocritical, camouflages itself and changes behind the luxury, the power and the competition. There is in the young artist from Alcoy a resentment feeling, roughness and simultaneously an aspiration to the “human man”. A demand for reality which all too often is forgotten where wellbeing sprays dries individuals in social egoism. Such thoughts of moral revolt can even be traced back to a certain American literary vanguard. Funk poetry comes to mind, or the novels of James Baldwin who, in a letter to Angela Davis in New York’s prison, denounces the tragic dilemmas of racism in the USA: “One would have hoped that just the sight of a black body in chains, just the sight of the chains, should now be so intolerable for the American people, a memory so unbearable, so as to spontaneously provoke a general revolt to break those bonds”, but now more than ever it seems that the Americans “value security with chains and cadavers”.

But the mind -blowing “urban massacre”, Miró’s originality and autonomy, no longer ethical- pietist, but radically common place, has attached to the very quality, to the absurdity of existence, so that the meanings are not only those of the documental truth, but also those of the distressing prefiguration of events which we ourselves do not decide. He sets out from the always new advertising and consumerist images that the industrial-technological society generates itself; he subtly takes them apart and puts them together, again turning around the image which in his painting he wants to represent as typical: “the objects” of the bourgeois life model and of private luxury (La model of 1975-76). Some figures of children painted with much love (L’espera (The wait) of 1972), but also with much dramatism (Sobre la guerra (On War) (1972). Figures that we find again, when the image is that of a universal judgement of class (Allende of 1973). Successive figurations that allow one to see how Mironian painting has experimented with the desert and with human emptiness (Nues de dolor (Painful nudes) of 1974), with an ideological-cultural sense that is always rich and specific but also so in love with freedom and with construction so as to reach the disarmed figure of the girl The Maja-today (1975). Finally, the “signs” and the “colours” of this living but funereal show of silhouettes in clear nazi or imperialist dress (Contra l’home (Against Man) of 1973-76), which, with animal gestures, always with a wild and devastating fury, look like the sad skeleton of a diffuse comic-book pornography (Finestra nua (Nude window) of 1979).

A voyeur of daily violence -the American pop artist Andy Warhol- in 1973 tried to reduce these scenes (as in the picture Pink Race Riot, in which “the perverse police and dogs of Birmingham take it out on a black man”) to the typical seriality of other images of his: those of the room with the electric chair, those of the great funerals with Jacqueline Kennedy, and the others with the weekend’s traffic accidents. Nevertheless, he did not manage to insert the black man in the routine, ritual series of dally tragedies. The Warhol present is rich in past and in future; it is an overfilled bag of Gingsberghian duration which is created on the fabric with silk-screen, according to the repetition of the same photograph always about to melt away in the next movement, but identical and fixed. On the contrary, Miró’s time is of an isolated sequence, scientific and pointillist; it seems to be populated with happy, multi-coloured people.

The Spanish artist, nevertheless, paints this time with a cold, glassy polychromatic technique, with a meticulous divisionism, mental and not optical, that disintegrates and deconstructs its false reality, and reveals its in consistency: a solitary still that also marks the pictorial rhythm of the mythe solaire méditerranéen (Mediterranean solar myth) and of Latin-Spanish lyricism for the reality of the fight, of blood, of the massacre, of political exodus, of an active stance-taking. That an ideological will should correspond to a true power of the imagination is confirmed by the inexhaustible visionary-psychological adventure which the penetration of confined space is, either through the hand-prints discovered by the children of Misèria i xiquets (Misery and kids) of 1972, where the “signs” are fanatically anthropomorphic up to the point of almost forming a great metaphor of human alarm, or through urban life, although empty, inhabited as in Música fins la mort (Music till death) of the same year.

However, it is necessary to understand that these figures are persecuted from inside by projections of dramatic, violent content, palpitating with a restrained horror that eats away at them beneath the skin, eroded by a light which hangs over you like a cancer; but, in any case, more ill from “violent falangismo” than from racial injustice. A method and a constructive clarity of image prevail which, especially in the paintings of the early eighties -from Emigrar cap a la mort (Emigrating towards death) to Repressió no, cultura sí (Against repression, For culture) and Personatge esguardant Gernika (Character regarding Guernica)-, come from the American Rosenquist (the gigantism and the shock of industrial objects and signs on advertising posters), from the French Monory (the chases and murders in the streets and the Metro) and from the English Philiphs (sections of cars and their rationality of the multitude’s existence in big cities, suffocated by skyscrapers and the hustle and bustle of the sidewalks). The feverish assumption of that figurative search as a primary experience of fulfilling himself, from day to day, as a man and an artist, could appear to be a question of style, a cold and didascalian exercise, if it wasn’t Miró; experiences that in the end, find their poetic correspondence (of political revolt like an Arroyo or a Genovés) only in the depths of an extremely civilised earth.

V.

Antoni Miró’s pictorial sight clarifies and orders itself with Cirurgià a Euskadi (Surgery in Euskadi) (1986) and Temps d’un poble (Times of a people) (1988-89); the extension tends towards ample and objectively viewed backgrounds. And as always, as never before, the synthetic strength of the plastic image represented with an inexorable chiaroscuro clashes and creaks through the contrast of the cut-out silhouettes à plat distributed around full hands: repulsively conformist silhouettes sometimes inspired by dépliant (leaflet) illustrations of fashion. A series of paintings like this follows -Dolor d’amar (The pain of loving) of 1999, Ingenuitat (Gullibility) of 2000 and Decorativa (Decorative) of the following year – which should be said to be marked by the pleasures and seductions of intimacy, given that the theme which nearly always dominates is of an “interior” livened up by the apparition of a female body. But the feminine presence is hardened, vulgarised by every possible garment popularly worn, more or less vulgar, with an exhibition from a supermarket catalogue, perhaps with some or other osé (daring) garment added.

Of course, Miró is certainly not the first to visit these “paradises for ladies of our time”, suspended between vulgarity and refinement, normality and perversion, provocative sex appeal but at the same time, controlled, also converted into a fruit for the masses. For example, certain English pop artists have arrived before him, and Miró has no problem in recognising this; in this way he tranquilly seems to cite Allen Jones, sure on the other hand that his “treatment” will give thickness, complication, and obsession to images that, nevertheless, in the English man can only be appreciated in a superficial tasting. Also because our artist is always prepared to resort to the tough and cruel weapon of subdivision; his women are never completely described, not even in sculpture, but manage to reveal before our eyes only some anatomic details: the abdomen and legs, and the feet with shoes on.

It is necessary to demystify objects to capture the most authentic reality, but it is also necessary to demystify their contents, in the rigorous debate against inheritance and cultural habits, as well as against facile collective persuasions. Miró, not disposed to abdicate, ponders between two patterns to be knocked down to reach a more authentic, new dimension of reality: cultural tradition with its riches and norms, and the mystified face of current reality just as it presents itself to us through the network, “direct” and with hegemony -although because of this no less certain or believed- of the mass media. And his drama is that of understanding how our own humanity feels attracted by both patterns in the end, but at the same time, it is clear that neither of the two can give us the measure of their most authentic nature and, above all, of their most authentic destiny.

In the Mironian rêverie a new dimension appears: the memory that permits a singular way of putting together different images, outside the preceding unity of time and place. It is a memory in its materiality, symbolically made current, which is created again in re-readings of recuperations of images of old maestros (Miguel Ángel, Velázquez, Goya) or modern ones (Picasso, Dalí, Miró): a memory, however, temporarily transgressing in its packaging, like Isop busca músics (Isop seeks musicians) (1981-91) and Dialogant (Conversing) (2001).

Looking inside the history of art has motivated the deeply reflective character of Miró’s figurative tékne in the last four or five years, his infinite worry. He reflects on the human condition in an implication that, from individual memory, the very thoughts, the very feelings, goes to a successive explicitness almost of a background of collective irrationality (Hiroshima & Tornar a casa (Going home)). His “allegorical eye” looks objectively at ghosts, nightmares, memories, and presences, attributing everything to material evidence of image that in the emblematic language of his narration, in a permanently lit up and emotively captivating chromatism, he compares them to the great urban scenes -Chénge de world and Torres bessones (Twin towers)-, that give way to solid pictorial constructions, in which his characteristic new view is developed with the certainty of representative objectivity, far from the interference of direct emotiveness and directed at a soaring and almost metaphysic al narration, where in any case, sometimes, precisely, allegorical intentions are insinuated.

I believe that Miró’s most recent works, from Manhattan triptych to Grup en moviment (Group in motion) and La Rambla, are a meticulous strategic relief about the relation between power and the act of creating the work, an extraordinary recollection of the presence of pictura pinges, of creative power at the very heart of the act. As for the movement, Bachelard has given, in La poétique de l’espace, an emblematic definition: the movement is the act of power in as much as it empowers”. This means that artistic creation is not, according to the common image, the irrevocable transit from a creative power to the work being acted on; it is, rather, the conservation of the power in the act, the giving of existence to a power as such, the life and almost the “dance” of the artist’s fantasy. Here, on the vibrating surfaces of his burning metropolitan scenes, Miró has finally found his atelier (workshop): The artist in the studio, as the ideal title should sound to his unsettling and metamorphic musée imaginaire (imaginary museum).