The wind of the people

Carles Cortés

What exactly are the winds of the people to which Miguel Hernández is referring in the poem “Vientos del pueblo me llevan” (The winds of the people carry me)? When this poet’s work was irst published on 22nd October 1936, the Spanish Civil War had been raging for three months following the coup staged by Franco. Hernández published this poem in the magazine El Mono Azul, a publication printed by the Republican faction under the auspices of the Alliance of Anti-Fascist Intellectuals in Defence of Culture. The magazine took its title –meaning The Blue Overalls– from the uniform worn by the militia fighting on the front and its purpose was to convey messages in defence of the Republic and Democracy to the soldiers, against the Fascist uprising. Reading this poem makes its interpretation immediately clear: the poet is striving to raise morale among the Republican troops by defending a victory of the ideals represented by those who support the legitimate government. It is a hymn to hope, to the defence of freedoms and strength of spirit in the face of adversity.

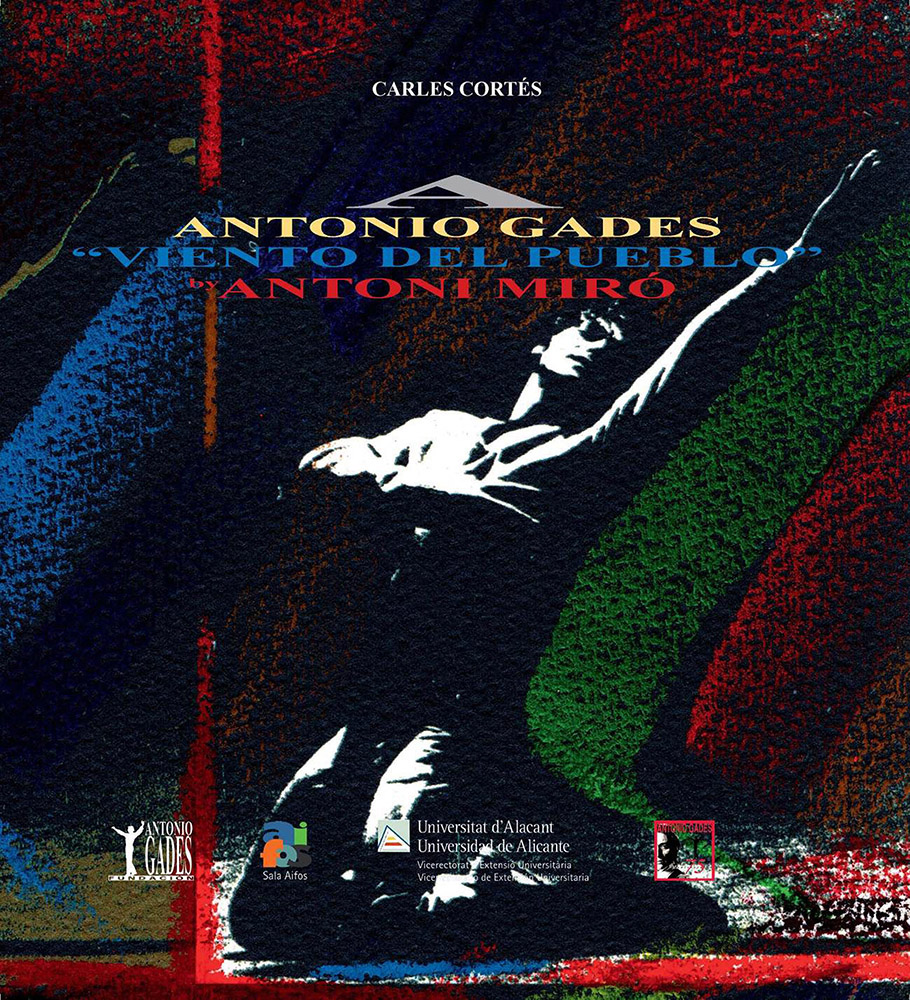

That is the ultimate meaning of a poem in which the painter Antoni Miró found inspiration for a new series of twenty-four digital graphic works on canvas and paper, with varying dimensions, which take their titles from the first twenty-four lines of the poem. This is yet another demonstration of this artist’s determination to make explicit use of the names of works of art, within a series entitled “Sense Títol”, which he has been developing since 2001; an immense series of creations which he has been working on since then and which share a common didactic and communicative intention, as the artist himself explained in an interview he gave before creating this series: “I want people to understand what I am trying to say, which is why I try to include in my paintings certain keys to their interpretation: a relevant date, a deformation, a colour” (Saó, 05.94, p. 26). Miró has in recent years sought to achieve a greater specificity of reality without neglecting the critical and interpretative sense of everyday life developed in previous collections. We must, therefore, understand the use of literary references in his work, for example, to Ausiàs March, Salvador Espriu, Joan Fuster and Miquel Martí i Pol, among others.1 On this occasion, the most socially-committed and critical poetry of Miguel Hernández has stirred in the painter reflections about another emblematic figure in his human and ideological formation: Antonio Gades.

The same year that Miguel Hernández published this poem, just one month later in fact, the dancer Antonio Esteve Ródenas -later known by his stage name of Antonio Gades- was born on 14th November in Elda. Upon his death in 2004, Gades bequeathed his legacy to his friend Antoni Miró, who felt the need and the drive to intertwine his art, the art of dance, and the words of the poet, the preference shared by them both. The series entitled “Viento del pueblo” (Winds of the People), therefore, is born from this symbiosis, between three axes of interpretation: the poetry of Miguel Hernández, the dance of Antonio Gades and the painting of Antoni Miró. The concurrence of languages has been a continuing fact throughout the history of art and the study of this phenomenon even more so. Such is true of the seminal book Laokoon (Laocoon: or, The limits of Poetry and Painting, 1766) by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing2, who concluded by affirming the superiority of poetry over painting. This debate began over two centuries ago and has motivated hundreds of artists who have felt drawn to the blending of two disciplines such as painting and literature; drawn to experimentation in the way that the critic Jordi Condal was in Los espacios de la creación poética: ¿territorios fronterizos?, considering that “the boundary between that which is and is not poetry is not always clear, and it is in this territory that experimentation flourishes” (Condal 2005, 53). That is, therefore, the challenge: to view this new exhibition of Miró’s work as a symbiosis between three languages: poetry, dance and painting.

What is the message sought by this graphic artist? The link between the words of Miguel Hernández and the expressiveness of the dancer’s body is not gratuitous. Perhaps now more than ever, Miró aims to defend the strength of the people, the struggle of individuals against the drift of society. As Daniel Bergez (2004, 149) pointed out in his analyses of interrelations between simultaneous displays of painting and literature in other artists, “les différences irréductibles qui les séparent sont alors autant de tremplins pour l’imagination créatrice”. The representation of a single reality or emotion through two artistic discourses chosen by the same artist, as is the case here, undoubtedly offers an interpretative reinforcement towards the reader-spectator. As we see in the introduction to comparative literature (1975) provided by Ulrich Weisstein, we can talk about a “reciprocal illumination of the arts”, where the result of Miró’s work3 is a kind of poem-image resulting from the transposition of the visual to the verbal element, so that the interpretation of discourse is not possible without the interaction of the other.

The origin of the collection we are presenting now is, undoubtedly, the knowledge shared by two eminent artistic figures from this region: Antoni Miró, from Alcoy, and Antonio Gades, from Elda4. As far back as 1964, aged just 20 at the time, the painter noted in his journal the impact that Gades, dancing had had on him; three years later, Miró saw him perform in Madrid, marking the start of a relationship that came to an end forty years later with the death of the dancer.

The friendship between the two was strengthened by the time they shared in Altea, where Miró settled after he returned from Dover in the UK at the start of the seventies. The atmosphere in Altea, in the area of La Marina Baixa, was more open to the artistic creativity of painters and welcoming to all kinds of artists. Miró recalled in 1970 his experiences in Dover in an interview he gave to Primera página: “I went to England thinking that it would be something else; I wanted to learn a language and work in peace. Everything was wonderful but after I had been there for some time, I realised that I preferred my own country. It’s true that people there are better qualified, better trained, but I find a greater restlessness here”. On 22nd July 1972, Antoni Miró held an official opening for his studio in Altea, attended by various critics and fellow artists such as Tomàs Llorens, Ernest Contreras and Manuel Vidal, among others. It was his study-home, an art gallery, home to many exhibitions and even mentioned in the account of the poet Vicent Andrés Estellés:

I went to Altea with Antoni Miró, to the place where he lives. [...] I saw Miró’s work, admirable, spirited and proud, rich in layers of rage and tenderness, excruciating chronicle and action plan, peopled by murals. His work, in cycles of extraordinary clarity of argument and mental cohesion, was offered to me like this, compact. I was literally captivated. [...] I have not finished. The work of Toni Miró reaches delicious extremes. I am referring now to his other work: his house. Everything is dominated by the pure, simple and traditional lines of Altea and it uses space in unexpected ways, in a happy game of planes, roofs and stairs. It is a delight [...] true to traditional architecture, with occasional allusions to the most remote riu-rau. (Las Provincias, 25.07.73)

His studio space in Altea, Galeria Alcoiarts, exhibited work by renowned artists such as Antonio Suárez, Rafael Canogar, Eusebi Sempere, Arcadi Blasco, Salvador Soria, Josep Guinovart, Daniel Argimon, Joana Francés and the sculptor Pablo Serrano, among others. The group of intellectuals who would often gather there included Antonio Gades and his partner at the time, Pepa Flores.

What interested Miró and Gades about this seaside town at that time? Undoubtedly the atmosphere of freedom and cosmopolitanism at a time when in the final years of Franco’s regime, it was not always easy to have a comfortable space for artistic activity. The two hit it off immediately; they soon realised that they had many personal and ideological points in common. Their proximity to self-proclaimed progressives and left-wingers built a friendship that endured until the dancer’s demise. Perhaps, the following words spoken by the painter during an interview he gave at the time might perfectly illustrate why intellectuals such as they decided to live in Altea: “I am not interested in whitewashed houses or the luminous quality of the landscape. I prefer the interior horizons of man, the light of ideals and of human hopes, the shade of pain and humility which, when turned into art, can make men and the social environment in which they live better.” (La Verdad, 07.07.74). It is this concern for the individual that shaped his work in the seventies and which may have brought Miró closer to Gades and vice versa; an artistic objective highlighted in 1973 by the Swedish essayist Joan Fuster5:

The painting of Antoni Miró is born from the most confused contradictions of Valencian society: from a phantom that we refer to as Valencian society. It has a virulence that sits astride ironic and epic. Could it be any other way? There are many Valencian painters that paint the proximal void: a landscape, a face, objects. Antoni Miró takes risks with subjects that ingenuously — and to suck our thumb—, at times, we usually term universal. They are not universal because they feature blacks, the spectrum of the CIA or a scene from Vietnam. [...] Miró looks beyond, deeper.

The positioning within Joan Fuster’s Valencian context contributes specific value to Miró’s work and is fundamental in order to understand the interest he aroused among both critics and his fellow artists, a skill that Miró received from Fuster and which, in the case of Gades, would be found in his very awareness of the defence of human values; an admission that the dancer himself made to Pilar López, the teacher from whom he learned what he called dance ethics, in other words, the ethics that makes action itself the sole objective of dance, without searching for easy applause: doing things without deceit, without prostituting them, doing a dignified job without expecting an immediate result. An artistic and critical determination in relation to the society which encompassed the artistic activity of these two friends. They also both displayed a similar conception of their career. Gades rejected the label of artiste or maestro, so commonly used among dancers. He saw himself as a cultural worker, a person dedicated to its expansion, to its development. Highly aware of himself as a figure, he said: “dancers must be the jesters of culture. It greatly saddens me to think that truly great igures had to dance in bars and restaurants for tourists who were just looking to have fun, instead of seeing them as a cultural manifestation”6. Miró, on the other hand, has on several occasions referred to his profession as an “art worker” in the way that other people are proletarians of industry or of companies: “all capitalists should be put to work and all workers should have food to eat. That is what this society needs.” (16.12.68)7; a reflection that could encompass the critical meaning of these two artists and the early finality of their work, as Miró once again explains a few years later:

I find that most art workers are ostracising us and times are not smiling on us. We are paying the price for being anti-establishment, and this seems to be perpetuating itself. In the end, the State is there to squeeze citizens, as always; those who protest, come off worse; and it seems it will be this way forever. (31.12.92)

In Altea, the two shared a moment of major intellectual and artistic activity. Gades, having begun his relationship with Pepa Flores and debuted Bodas de sangre, following the assassination of several Basque militants ordered by Franco, had decided to retire and seek refuge in this town in La Marina Baixa. The dancer’s indignation surpassed his expectations, which led him to choose provisional retirement. It was not until four years later, in 1978, when, thanks to Alicia Alonso, in Cuba, he returned to his artistic activity, which soon brought him to the directorship of the Spanish National Ballet in one of the most productive stages of his career. It was during this period of time –between 1974 and 1978– that he first came into contact with the painter Antoni Miró who, in turn, had embarked on an intense collaboration with the Italian art group Denunzia. Hence, together with painters such as Bruno Rinaldi, Comencini and the critic Floriano de Santi, he took part in a movement that sought to condemn injustice and, above all, undertake a head-on attack of any residual displays of Fascism that still existed in Europe in the seventies; a critical sense similar to that which had drawn Gades to the production of Bodas de sangre, reclaiming the work of Federico García Lorca and its survival after his assassination. Miró took part in the collective portfolio Omaggio alla Resistenza by Gruppo Denunzia which provided the starting point for some of his later paintings, such as Resistenza-Partigiani (1975).

The clear political stances taken by both Gades and Miró led to attacks being launched against them in the form of graffiti on the walls of Altea. Fascist slogans were daubed on one of the murals designed by the painter, such as “Reds to the firing squad”, “We prevailed and shall prevail”, “Reds to Moscow and Miró to jail”, among others8. This insulting graffiti that appeared at the end of 1977 on both their houses and sparked numerous displays of solidarity from social and political representatives only served to highlight the long road that lay ahead for the Democracy that was just starting out in this country. Antoni Miró wrote in his journal: “the extreme right-wing Fascists have taken it out on me”, (01.01.78).

During these years, Miró also focused on denouncing Pinochet’s coup in Chile, a situation he condemned frequently in the conversations he shared with Antonio Gades in Altea. Between 1973 and 1976, he created anti-Fascist works impregnated with the artist’s repulsion towards the situation created following the assassination of Allende. At the end of 1977, Miró donated one of his works to the Salvador Allende International Museum of Resistance, Record viu (1973- 1974), a painting or quartet, Xile, and a metal graphic work entitled Xile 73-76 printed by PSAN (Partit Socialista d’Alliberament Nacional, Socialist Party of National Liberation), which included Pablo Neruda’s poem “Los sátrapas”. In the document written to accompany the donation, Miró expressed his feelings:

Chile was a hope, a lesson and a path towards freedom. The mercenary assassinations carried out under the orders of the executioner Pinochet sacriiced and sold an extraordinary nation. We see how history repeats itself, and I cried with rage that eleventh of September nineteen seventy three (as I would have done if I had been alive forty years previously). My Chilean brothers were falling victims to Fascism and I, powerless, could only protest a thousand and one times lest it ever be forgotten. (10.10.77)

During this period, Miró created a new series, entitled “El Dòlar” which, between 1973 and 1979, provided a tool to express various social concerns that were besetting him. The US currency was becoming a symbol for the excesses of capitalism, a motive for the oppression of humanity when placed in the hands of reactionary forces which were the object of socially committed artists like Miró and Gades. The words spoken by the painter in his interview with the newspaper Avui (08.08.76, 9) may be highly representative: “I have always had a go at America because the Americans have the most opportunity to screw others over. They have a system that allows them to do a series of fairly simple things: pay and screw over.”

The degree of social awareness of both Gades and Miró led them to participate -with other friends from Alicante and Altea, such as Enrique Cerdán Tato- in the demonstration in Alicante called by La Junta Democrática on 30th April 1975. The two believed, as their work reveals, in the social role of artists as a symbolic reference for their country. Events unfolded one after another and Franco’s regime, like the dictator himself, was in its dying throes. Political repression in the Basque Country had a strong impact on both of them, and they regularly attended meetings of La Junta Democrática together with Trevijano and Brosseta, as well as other politicians of the time.

In Miró’s studio, they gathered together with other friends who were involved in the political action. At the same time, Gades was painting every afternoon in his friend’s studio. The ideological interaction that took place between the two enriched their ideological principles. Miró created a living mould of his friend’s body which, many years later, he used to create several works.

The painter’s journal describes the atmosphere during the time they spent in his house: “Gades performs sections of his dances for me and we chat so that I can understand what he has done as a dancer.” (03.07.77). He used these images to make sketches and take notes for subsequent works that used the dancer as the artistic foundation. Hence, in 1989, as part of the series “Pinteu Pintura”, Miró completed the painting Amic Gades -Friend Gades-.

The two artists shared an interest in poets with a strongly progressive vein. Hence, in 1976, Miró collaborated in an exhibition entitled “A tribute to Miguel Hernández by the people of Spain”, through which a series of paintings, firmly committed to the defence of freedoms, travelled around much of the country. That same year, he took part in a tribute paid to the poet Rafael Alberti, held in several galleries around Barcelona, a homage that greatly pleased Gades, a close friend of Alberti and his partner, M. Teresa León, who had just returned to Spain from exile. The critic Daniel Giralt Miracle had the following to say about the painter’s civic participation: “Is it social realism, a kind of chronicle of reality, committed art? Miró has expanded beyond any of the boxes that could pigeon-hole him in one specific “ism”; the evolution of his work is firmly rooted in the pulsing of political currents and their dynamics. The artist is concerned with social facts, events and experiences, both locally and internationally.” (Avui, 13.03.77).

The critical spirit of these two artists led them to oppose the urban organisation plan drawn up by Altea’s Town Council: “they want to turn Altea into a huge depersonalised town, where only speculators live happily”, wrote the painter in his journal at the end of October 1977. They both participated in various demonstrations against the local government’s decision to free up land for construction. They also expressed their opposition in a series of protests against the conservative elements that had been maintained in the local patron saint festivities. In view of the scant support received from the local Left, which did not join the protest, Miró noted: “it is always very sad to observe the Left’s lack of solidarity and opposition, lacking in unity and taking approaches that are at times quite absurd.” (11.06.78). His friend Gades however, supported him, just as he did when Miró stood in the local Alicante elections for the BEAN party (Bloc d’Esquerres d’Alliberament Nacional, -Block of left National Liberation-).

In Madrid, through Antonio Gades and Pepa Flores, who ran the restaurant “Casa Gades”, Miró came into contact with Pedro Orlando, a diplomat from the Cuban Embassy, confirming the intense relationship that existed with Cuba’s cultural attachés. That year, Gades was living in Cuba and working with Alicia Alonso’s company where, as the dancer stated on several occasions, he learned everything which he subsequently brought to the National Ballet. Both Gades and Miró appreciated the Cuban regime’s firm support for culture in all its manifestations. Hence, for example, in 1999, Miró met up with Gades in Cuba. There, he was introduced to Pardo, the vice minister for the Cuban Institute of the Cinematographic Art and Industry, who, together with Rafael Acosta, president of the National Arts Council at the time, suggested he showed his work at the Wifredo Lam Contemporary Art Centre in Havana. It was then that he met the brothers of the Cuban President, Ramón and Raúl Castro, at the home of the minister Abelardo Colomé. At different times, both Miró and Gades have received the medal of cultural recognition awarded by the Cuban Government, proof of the interaction between these two artists and Cuba’s intellectual class. Miró also accompanied Antonio Gades when he went to collect the Cross of Sant Jordi presented by Catalonia’s Regional Government in 1999.

Given all the above, it is easy to understand the close and complementary relationship these two friends developed over time; two parallel existences that often revealed the affection and interest in individual works with the maintenance of shared friendships, such as that of the ill-fated Ovidi Montllor, who departed their company in 1995, having a major impact on his two friends. Perhaps the sculptural installation Gades, la dansa (2001) on the campus of Valencia’s Polytechnic University, is most representative. It is a compendium of thirty torsos cast in bronze, created by Miró using the live model he made in 1978, when the two were living in Altea. The sculpture stretches twenty-two metres in length and simulates the repetition of cinematographic language through the succession of metal pieces, imitating the movement of dance and, ultimately, the movement of cinema which so greatly interested the dancer. It reminds us of his participation in films such as Los tarantos (1963), Los días del pasado (1977) and Bodas de sangre (1981).

This dynamism, naturally, impregnates various images from “El viento del pueblo”, such as “Vientos del pueblo me arrastran” (The winds of the people blow me on), “Delante de los castigos” (At their punishment), “Que soy de un pueblo que embargan” (I am from a race that holds) and “Jamás ni yugos ni trabas” (Whoever yoked or hobbled), images built on Gades, dance scenes in which Miró has enhanced the perception of the body in movement, whilst at the same time tying it in with Miguel Hernández’s most powerful lines of protest. The poet sought to express the sense of rebellion, the protagonist striving to bring oppression to an end and for that reason he takes the model of beasts such as lions, eagles and bulls, over the submission of oxen. Hence, the praise of the strength of these animals receives in Miró’s images the succession of snapshots in which Gades was getting ready to dance, the rituals of staging his power, his dance aesthetic: “No soy de un pueblo de bueyes” (I am not from a race of oxen), “Yacimientos de leones” (the mines of lions), “Desiladeros de águilas” (the passes of eagles), “Y cordilleras de toros” (and the ridges of bulls), “Nunca medraron los bueyes” (Oxen never prospered), “En los páramos de España” (in the wastes of Spain). These are the paintings that take their titles from lines in the third stanza of Hernández, poem. These three artists, Hernández, Gades and Miró -who shared a very close geographical origin: Orihuela, Elda and Alcoi— have demonstrated in their trajectory a strong civic commitment and a belief in the dynamic action of the artist towards society; opting for the speciic action presented in the collection “El vent del poble” with the simile of the wind, in the case of the poem, and the duplication of images, in the case of the images. See, for example, “Y me aventan la garganta” (and readying my throat), “Y al mismo tiempo castigan” (and at the same time punish) or “Quién habló de echar un yugo” (Who spoke of throwing a yoke), lines in which the poet tackled the pressure of enemies against the freedom of the protagonist and which allow the painter to increase the mobility of the dancer in his studio. The overlaying of the three languages is clearly evident in pieces such as “Los leones se levantan” (Lions lift theirs), where we ind the dancer with his arms held high, preparing for the next step; all within a symbolic wrapping, the painter’s palette which, when linked to the poet’s verse, makes the three referential elements of the series simultaneous. Three languages, definitively, which were also present in the dancer’s artistic career in productions such as Bodas de sangre (1974), Carmen (1983), Fuego (1989) and Fuenteovejuna (1994), where the literary references are evident. The face of Gades, taken from several sketches made by Miró in Mas Sopalmo, constructs a series of paintings that clearly identify his personality with that of the protagonist in Hernández’s poem: “Vientos del pueblo me llevan” (Winds of the people carry me), “Desfiladeros de águilas” (the passes of eagles), “Quién ha puesto al huracán” (Who ever yoked or hobbled a hurricane) and “Prisionero en una jaula” (prisoner in a jail). This latter piece offers the last images of Antonio Gades, the individual held prisoner in the world, in this sense, of the illness that plagued him in his final years and which separated him from his friend Miró forever. A wind that sweeps through the existences of these three artists from our land who were undoubtedly committed to the development of freedoms. With their respective languages, they found the right means to express their feelings and their determination, as we can read in the first stanza of Hernández’s poem:

Vientos del pueblo me llevan,

vientos del pueblo me arrastran,

me esparcen el corazón

y me aventan la garganta.

The winds of the people carry me,

the winds of the people blow me on,

scattering this heart of mine

and readying my throat.

This is their voice, their energy, their will. “El viento del pueblo” encompasses a series that perfectly synthesises the simultaneity of languages and the shared desire to achieve a fairer and freer world; an undertaking that has endured over time thanks to the initiative carried forward by the Antonio Gades Foundation, led by his widow, Eugenia Eiriz, and his daughters. In this way, artists, dancers and musicians, with the wind in their face or behind them, can continue his endeavour. This is the message, his legacy; the path opened up by Antonio Gades, our maestro.

Bibliography

- Bergez, Daniel (2004), Littérature et peinture, París, Armand Colin.

- Condal, Jordi (2005), “Els espais de la creació poètica: territoris fronterers?”, Literatures, 3, pàg. 41-57.

- Cortés, Carles (2005), Vull ser pintor... Una biograia sobre Antoni Miró, València, Ed. 3 i 4.

- (2007a), “ABCDARI AZ (1995): poesia i pintura d’Isabel-Clara Simó i Antoni Miró”, 2n Col·loqui Europeu d’Estudis Catalans, Montpellier, Éditions de la Tour Gile, pàg. 101-128.

- (2007b), “Vull ser pintor: el diari inèdit d’Antoni Miró”, Diaris i dietaris, València, Denes, pàg. 443-456.

- (2009), “Pintura i literatura en l’obra d’Antoni Miró: la presència dels escriptors catalans”, Discurso sobre fronteras - fronteras del discurso: estudios del ámbito ibérico e iberoamericano, Poznan, Leksem, pàg. 553-566.

- GUILL, Joan (1988), Temàtica i poètica en l’obra artística d’Antoni Miró, València, Universitat Politècnica de València-Ajuntament d’Alcoi.

- Lessing, Gotthold Ephraim (1990), Laocoonte, Madrid, Tecnos.

- Weisstein, Ulrico (1975), Introducción a la literatura comparada, Barcelona, Planeta, 1975.

1. Consult our study “Pintura i literatura en l’obra d’Antoni Miró: la presència dels escriptors catalans” (2009).

2. We used the Spanish edition published by Tecnos (1990).

3. By way of an example, see our previous study “ABCDARI AZ (1995): poesia i pintura d’Isabel-Clara Simó i Antoni Miró” (2007a).

4. Without forgetting the origins of Miguel Hernández, from Orihuela, the leit-motiv of the collection.

5. Text produced in Temàtica i poètica en l’obra artística d’Antoni Miró by Joan Guill, p. 91

6. These quotations have been taken from Antonio Gades’ official webpage: http://www.portalatino.com/platino/website/ewespeciales/gades/antoniogades.html

7. Information taken from the painter’s journals. See Cortés 2005 and 2007b, chiely.

8. A friend of his, the writer Joan Fuster, received an attack on one of the doors to his home in 1978.