Antoni Miró’s committed and supportive art

Àngel Beneito

In July 1936 a part of the Spanish Army rose against a legally constituted government, which defined itself in the first article of its Constitution as a “democratic Republic of workers of all kinds, organized under a regime of freedom and justice”. In Europe, unfortunately, things were not better. In Germany, Hitler was the Chancellor long time ago, while, in Italy, Mussolini ruled with dictatorial powers. The confrontation between dictatorships and democracies seemed unavoidable.

In Sweden and Norway, knowing that Franco had taken up arms, the working class showed its solidarity with the Spanish workers. Immediately progressive political parties and trade unions as well as civil and cultural associations launched a campaign to help the Popular Front, initiative that led to a solidarity movement called “Let’s Help Spain”. As a result, in a short time Local Committees to Help Spain were created in almost every municipality, where thousands of citizens helped to send clothes, medicines and food to the Republican fighters and to the civilians, especially women and children suffering the horrors of war.

In order to raise public awareness and predispose people in favour of the Republican cause, the Committees to Help Spain distributed thousands of lapel pins with the text “För Spanien”, and they organized an uncountable number of meetings, demonstrations, lectures, solidarity parties and radio talks, while the most progressive press published a great number of articles, poems and drawings, made by radical authors, referring to the war in Spain.

This solidarity call worked effectively and the answer of the Scandinavian society was impressive: under the slogan “your struggle is ours” thousands of workers were able to gather large amounts of money which were used to buy tonnes of food (preserved food, milk, wheat, margarine, salted fish, cheese, sugar, chocolate, etc.), as well as soap bars, vitamins, surgical equipment, medicines, bandages, blisters of morphine, anaesthesia, etc., for Spain.

Once this was done, and having heard of the social and health deprivation, the Spanish people were suffering, both the Swedish and the Norwegian Committees decided to join their resources and to collaborate with the International Health Central and with the International Committee for Children. On behalf of both committees, Georg Branting (Chairman for the Swedish Committee to Help Spain), spent a good part of the thousands of crowns gathered both to set up host families and orphanages for the children who had lost their parents, and a complete war hospital: the Swedish-Norwegian Hospital in Alcoy, which would care for the soldiers who were falling wounded in combat.

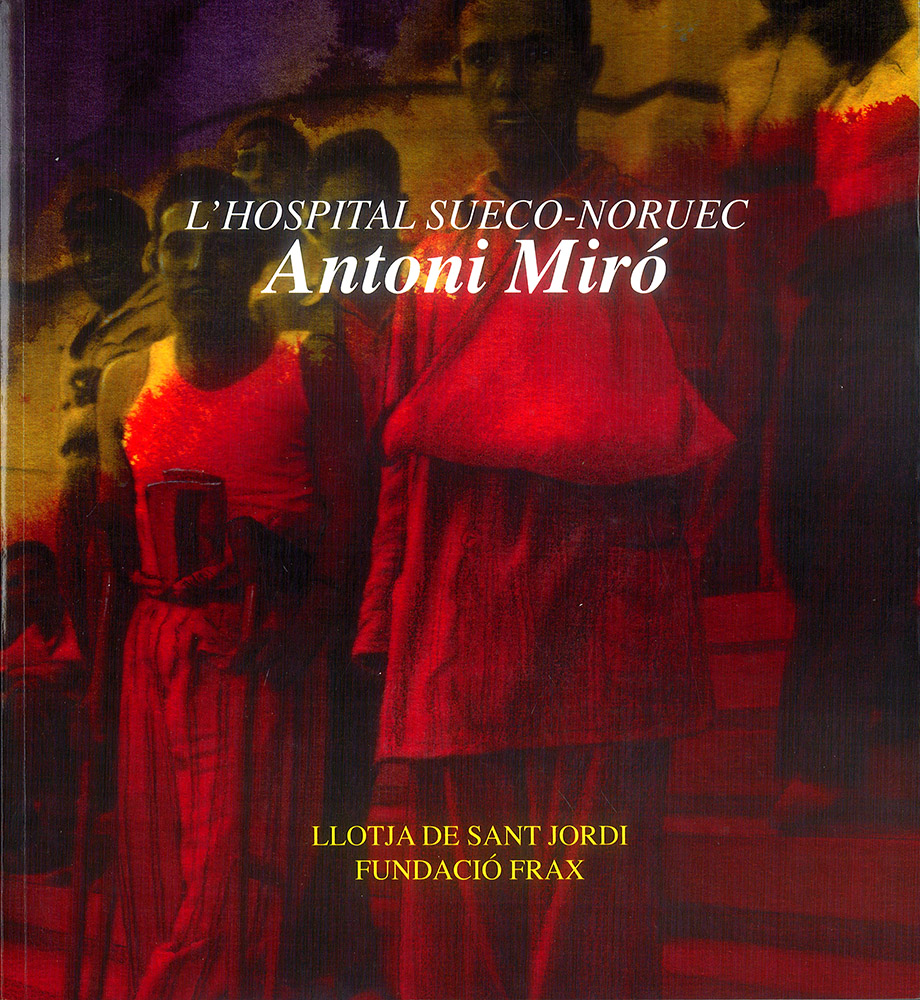

Well then, this gesture of solidarity and altruism of the Scandinavian people with the Spanish people is magnificently reflected by Antoni Miró in the series The Swedish-Norwegian Hospital, which commemorates the 75th Anniversary of this ephemeris.

Antoni Miró’s artistic career as a painter, sculptor or engraver, it does not matter, has always been characterized by keeping some identity signs which distinguish him and make him unique, being always at the service of and according to social and cultural commitment. He has never worked unintentionally: his work is denounce, cry, criticism, irony, recognition... The series “Black America” (1972), “The Dollar” (1973-80), “Paint painting” (1980-90), “Vivace” (1991-2001), “Without Title” (2001), “Wind from the people” (2011), among others, are an eloquent sample of pictorial, graphic and plastic combination which is materialized by means of a marked political, social or cultural intention. Miró, an observer from distance, a man almost cloistered at Sopalmo cottage, is, however, a conscious and critical lighthouse of the society surrounding him, the same society he analyzes and denounces through his metaphoric interpretations, images full of strength and commitment that do not leave us unmoved.

Well then, I must warn I am neither qualified to write a usual art criticism nor these lines are trying to do it. This being said, it is beyond doubt that contemplating the work Antoni Miró presents to us in this series, the “Swedish-Norwegian Hospital”, is contemplating the work of an artist committed to history and to present, to past and to our time through the use of textures, shapes, colours and intentions, certainly testimonial and provoking intentions, which shake the viewers’ conscience to sensitize them and not to leave them indifferent.

It is not the first time that Antoni Miró goes into the traces of historical recreation. Quite the opposite, history and characters of historical significance have been a source of inspiration, nearly constant, throughout his entire career. We must remember the canvases “Vietnam-1 ” (1968), “Imperial spears” (1976-77), “Interlude” (1998), “Hiroshima remembrance” (2002), “Kuwait Desert” (2004), “City without exit” (2005), “the tree of Gernika” (2008), the series “The exile 1939” (2009) or “President Companys” (2010), among many others, with clear reference to the Vietnam war, to the Austrias’ imperialism, to the Second World War, to the nuclear holocaust suffered by Japan, to the Gulf War, to the Nazi genocide in the extermination camps, to the claiming of the historical freedoms of the Basques, to the Republican exile or to the subsequent repression and loss of freedoms that happened when the Spanish Civil War ended.

In the present exhibition series, Antoni Miró recreates, artistically, boldly and courageously, a historical event which Alcoy, his hometown, witnessed during the unfortunate Spanish Civil War: the setting up of the Swedish-Norwegian Hospital in the city. But his work, deeply committed to history, goes further on presenting the viewer a whole sequence of images reconstructing, step by step, every one of the most important and overwhelming events of this magnificent story of international solidarity, of which the Spanish Republic was custodian in 1937.

Red, yellow and purple are the dominant and ever-present colours in the works composing this series, with a clear intention to remember and pay tribute to the Second Republic and to the men who fought for it, in order to defend it from the military uprising.

Now, seventy-five years after the setup of the Swedish-Norwegian Hospital in Alcoy, Antoni Miró’s work makes didactics, when showing the viewers a historical event and sensitizing them on it, an event the dictatorship and the passage of time took care to erase. His canvases, pure artistic and historical recreation, show us the mass demonstrations held in Sweden and Norway for the Spanish Republic, as well as the solidarity of the workers of those latitudes when they were raising money and supplies, at factories and streets, which were used to reduce hunger and to provide medical assistance to the combatants and the civilians who were suffering the war. But he also places, before our eyes, the faces of the wounded soldiers (some of them little more than children) and the amputations they suffered, as a metaphor for the pain caused by the military uprising, and the painful warfare, and the dignity of the Spanish people, and the hard repression suffered just after the war. In short, a whole argument converted into history and denounce of the human condition: the most sublime part, solidarity with equals, and the lowest and worst one generated by a war conflict.