Mais c’est le tour d’Antoni Miró (But its Antoni Miró's turn)

Néstor Basterretxea

- Mister Miró, you have forgotten a bicycle, five umbrellas, a toolbox and a metal tweezer!

(The waiter is shouting at Toni)

- Are they the colour of a sepia daguerreotype?

- ...? (He does not answer)

- Save it all, it is one of my engravings. And the still life containing a polyhedron with a white and a black bottle, and again the white one reflected in a hexagonal mirror, is another one of my engravings that you should also save.

Night falls on Mas del Sopalmo, sneaking in quietly just for the childhood pleasure of catching Toni unawares (he is a tireless night worker) in the space of his large studio where the millimetre is the measure which determines the manic order of the things he needs to be surrounded with.

He will work until sunrise, and as with Count Dracula, the first hours of the new day will put him in his coffin, sorry, in his bed, so he can sleep deeply. “If one is not obsessed, one is lost”, Jorge Oteiza used to say.

The opportunity and the silence helped me to walk slowly, paying attention to what I saw, when I was left alone in the house. Toni had gone I don’t know where; Sofia, his wife, was doing her job as a paediatrician doctor in Alcoi since the early hours; and the strapping Ausiàs, I imagine, squeezing love with his girlfriend somewhere about.

Paying attention, that is, to try to understand the multiple adventure of the efforts that, to my eyes, seemed like a motley repertory of objects secretly connected to each other, I suppose, and composing the vast and surprising aesthetic body that Toni Miró’s work turns out to be.

A human skull seemed like alabaster against the light; Toni keeps it by a pair of wax like vases made of fine glass that impregnate the skull with a halo of mystery.

A giant penis belonging to some ancient god, maybe Greek, in brilliant gold bronze, announces the population of penises spread out into every corner of the house.

A succession of black folders, in order and easily looked into, save the memories of our friend’s amazing imagination.

And he tells us in his painting how René Magritte makes three gentlemen in Sunday finery, wearing suits and bowler hats, go crazy; without understanding how King Carlos III (the most used one by Toni) happened to end up with them, under a cloud of wrinkled, ochre newspapers, under a sadly blue rainy sky.

He has drawn Marilyn Monroe under the wide brim of a light-coloured picture hat, between a Picasso bottle and guitar, with the expression on her face showing she does not understand life’s complexity.

To the erotic brevity of the Duchess of Alba’s waist, surprised and red-faced because she has had to dress in a hurry (while Goya did the same), Toni has added a packet of Ducados, those of republican smoke and flavour, so as to mortify her.

Some noisy puppets, covered in cylindrical baskets and the wires that tie them down, leave their hiding-place to breathe the country fragrance: to shout in glee because the sempervivum are making up lawns on the edges of the Mas del Sopalmo.

- Who says the violin tree does not exist? Is it not true that I had a beautiful picture of Toni’s in front of me, and that it was a long blue sound between the dark branches on the edge of the fog?

The only suitcase that was not Úrculo’s is abandoned in the yellow of a translucid room, and only the person who has left it there, painted, knows if the suitcase goes or returns.

Hieratic and detained in the dense shadow of a corridor, Albert Dürer complains:

- What am I doing at the Mas del Sopalmo, engraved by the owner of this house and suspended from the wall, when I should be in Nürnberg trying, once again, to meet Martin Luther!

Because he does as he wishes in his own house, Toni appears under a white light, between General Spínola and his Flemish opponent, in the humiliating moment of capitulation as he gives the Spaniard the keys to Breda, as created by Velázquez. It is an irrepressible act, this iconoclast tendency of Toni’s as he destroys realms, nobles and military glory because he understands them to be imposed organizations, icons of tyranny.

Despite his quietness in speaking and habits, Toni sometimes reaches the pointed sharpness of Buñuel’s knife, Le Chien Andalou. He leaves the beaten and sacramental path of Saint John’s “Apocalypse” to position himself in humanism, always close to those who suffer injustice. He knows well that Apocalypse is now, because this world boasts weapons that kill more and better.

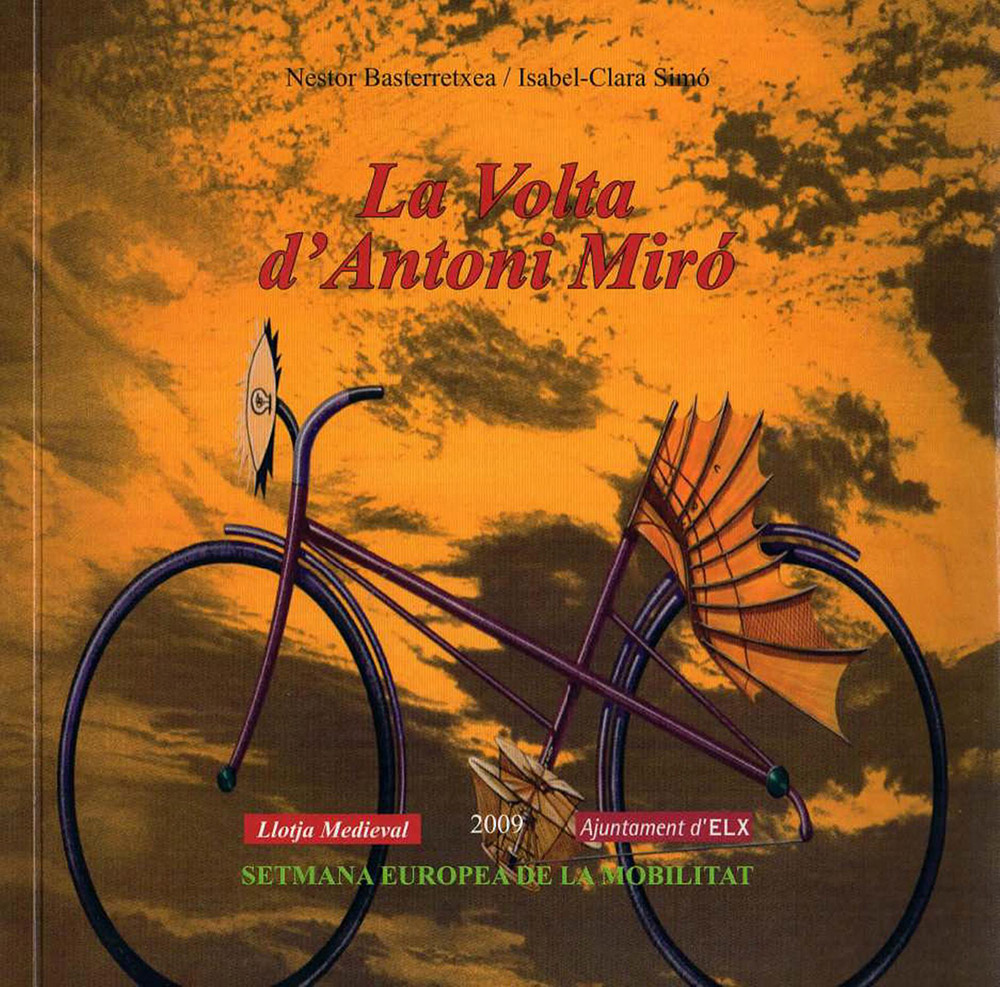

Like a sponge that wets itself in different water, Toni changes his subject and becomes interested in different kinds of bicycle. His impossible artefacts.

France is leaning on its balconies or waiting patiently on the blue curves of its highways because the Tour is arriving from Paris.

The bicycles Toni has painted run fast and in single file. The one in front of the group has an open black umbrella and a package on the back wheel; the following one has two pointy and deadly bull’s horns in place of handlebars; and yet another one is decorated by the travelling knife-grinder’s tools. Another one has three seats on it, probably to insure triple-traction, another one sports a red barretina1 where the seat should be... and number twenty, last in race, is an enormous fish balancing with difficulties on the bar of a bicycle.

Toni’s bicycles run across France without riders to guide them. They ride all by themselves. Painted.

- Mais, c’est le Tour d’Antoni Miró!

Another twist of the screw of the imaginative coordinates of our friend, and we find ourselves in the erotic jubilation that the game of possession of a woman’s voluptuous body is. There are so many nude, engraved, exhibited women in the galleries of Mas del Sopalmo that one has the exciting feeling that there are hardly any women that bother to any longer dress.

Amen, farewell.

P.S.: and, of course, his well kept obsessions: The large eyes of Picasso and Freud, Gaudí, Fidel Castro and, above all, Ché Guevara, a tough and pale body, machine-gunned and killed in the high sierra of Bolivia.

1. Cap worn in Catalonia shaped like a sack and made of red and black wool