Psicoanàlisi de la pintura (The psycho-analysis of painting)

This work explains one of the keys to the “Pinteu Pintura” (Paint Painting) series, of which it is a part. Romà de la Calle referred to the strange obsession that characterised this stage of Antoni Miró’s work. He did so in a volume that was published the same year by the Canigó publishing house. He wrote of the self-referential property of language, the ironic use of the repertoire of images provided by the mass media and by the history of art, intertextuality, and a twofold awareness: that of the world around us and of painting itself.

It is clear that this awareness stems from combining and reflecting on a set of elements. Yet there is more to it than this. Chance and the artist’s expressive impulses also play a role in pictorial creation. This is the issue raised by this work.

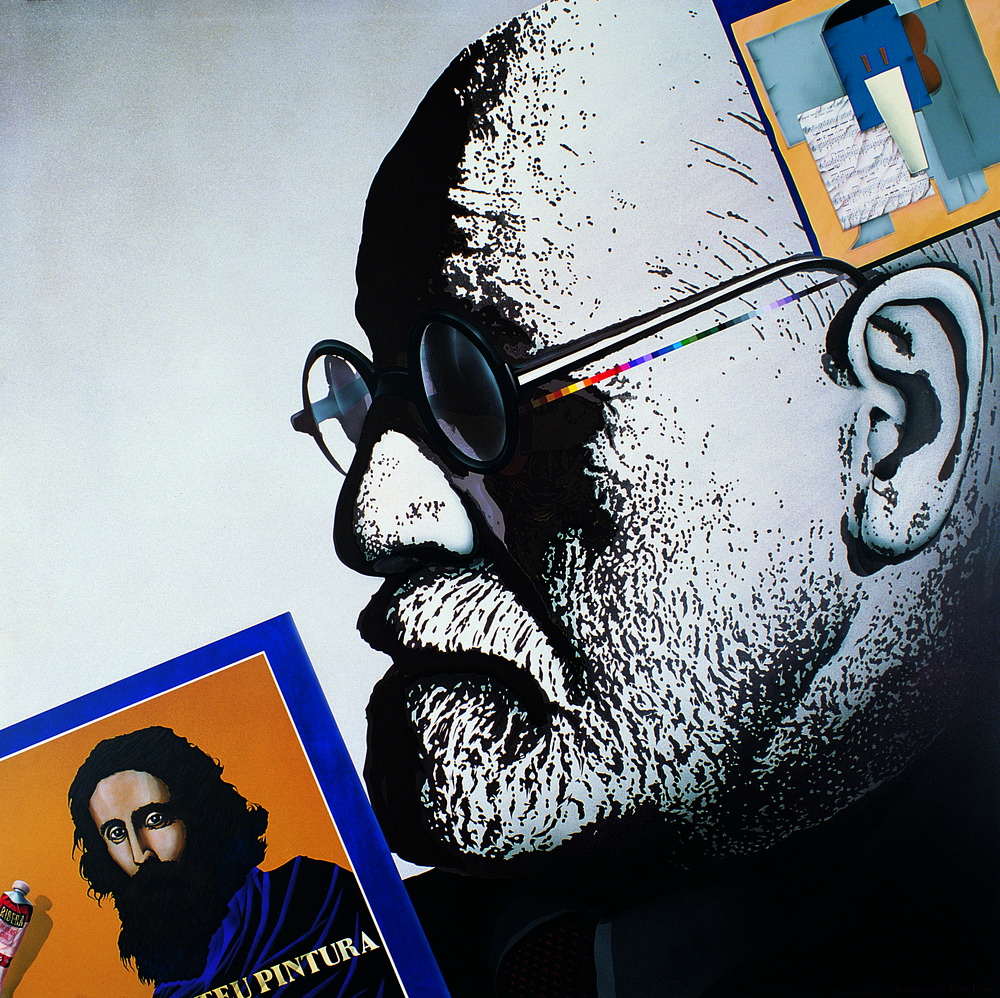

This portrait of Freud is supplemented by two elements. On the one hand, there is the dust-cover of the book on the “Pinteu Pintura” series — the works the artist busied himself with in the 1980s. The cover had a reproduction of the Sant Pau Fumata painting (1981-82), in which the face of the Saint of Tarsus was shown as it was painted by Spanish artist Ribera, together with a tube of acrylic paint. As so often, the canonical reference was metaphorically mixed with other elements in common use. Ribera’s painting is thus alluded to twice.

In addition, there is what one might call a figurative Cubist collage. The painted fragments (papers, card, a musical score) take on fairly regular shapes and strongly hint at an elephant. This animal has sometimes been associated with the id in psychoanalytic theory, the stamping ground of primitive drives and desires. This takes us back to impulses and the scope they give to artistic expression. Yet, in addition to the artist’s intuitive, irrational traits as a creative agent, Lacan’s use of the word ‘elephant’ to explain language conventions in describing the real world is also worth mentioning.

It thus seems that the artist accepts Freudian postulates, suggesting that what the artist had been doing up until then involved expressing judgements based on his most inner self. He does so by insisting on the overlap between the theme of the work and the disciplinary means with which Miró renders it. Painting is not only a vehicle of expression, representation or reflection, but can also become the object of all three.

The work is a large-format one which sets a clear precedent for Miró’s later “Personatges” (Great Figures) series and is based on a diagonal composition. There are three main elements on the square canvas: the book cover, Freud’s face, and the collage, which are laid out along the oblique direction set by the ‘temples’ (side-arms) of Freud’s glasses, and thus his own stare. This diagonal line is highlighted by a thin parallel multi-colour strip, which contrasts with the black-and-white portrait of Freud and helps ‘bridge’ the more colourful collage and book cover at either side.

Santiago Pastor Vila