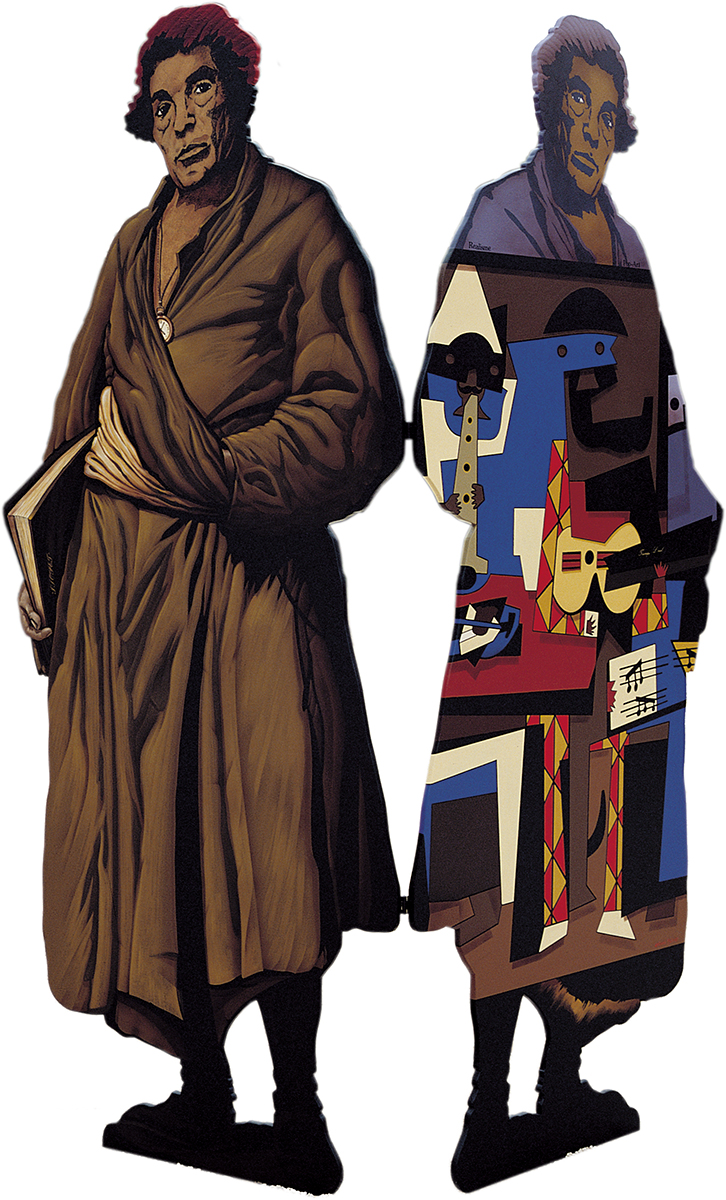

Isop busca músics (Aesop seeks musicians)

In Miró’s ‘Paint Painting’ series, it is common of the artist to superimpose various fragments of works that, though all make up the canon of art history, are drawn from very different periods and styles. The resulting contrast reveals new interpretative facets. A classic figure is usually used to overlay more recent themes and creations, as in this case.

This ‘object-painting’ consists of two flat representations on wood of Velázquez’s Aesop. One of them maintains the original orientation and is minimally altered. The other is reflected, as if in a mirror, and is overlain with one of the two versions of Picasso’s Three Musicians. This work is complemented by a similar one representing Menippus.

The first figure stands out from the background and the secondary attributes: a cube, clothes, and crown. By contrast, the book of Aesop’s Fables is kept, albeit in a less battered state and with a hand-written title. The figure is given a chain watch, an allusion to time, which structures music, and the inevitable repetition of cycles, and history in general, in the expected terms. In fact, time is the factor that gives rise to the literary genre encompassing fables.

In the fable of the musician dogs, Aesop explains that “some dogs, which are a shameless and interfering race, learnt to make music and kept at it until they became men, who continue singing to this day”. The title of Picasso’s picture makes it clear that the dog hiding behind the legs of the three characters is not a musician but, under an ironic consideration, may well become one. Be that as it may, the Greek fabulist seeks this or another musician to add sound to his texts. The dog is even more invisible in the cropping made by the framing, justifying the need to find him.

Nevertheless, going beyond literal interpretations, this piece offers a reflection on pictorial styles. The most figurative realism and the most media-popularised Pop Art affect, as happens with the rest, the articulation of the message. The trompes l’oeil and the dislocation of meaning that the artist conceives are at the core of the interpretation he wants to obtain from the viewer.As Romá de la Calle brilliantly notes, Antoni Miró brings “morphological elements” but “hides the keys to the syntax used to compositionally structure and link those elements”. That is why, in Prof. de la Calle’s view, the work puts “the viewers’ hermeneutic skills to test so, from this combination of elements, they can freely execute their own interpretative options”.

Santiago Pastor Vila