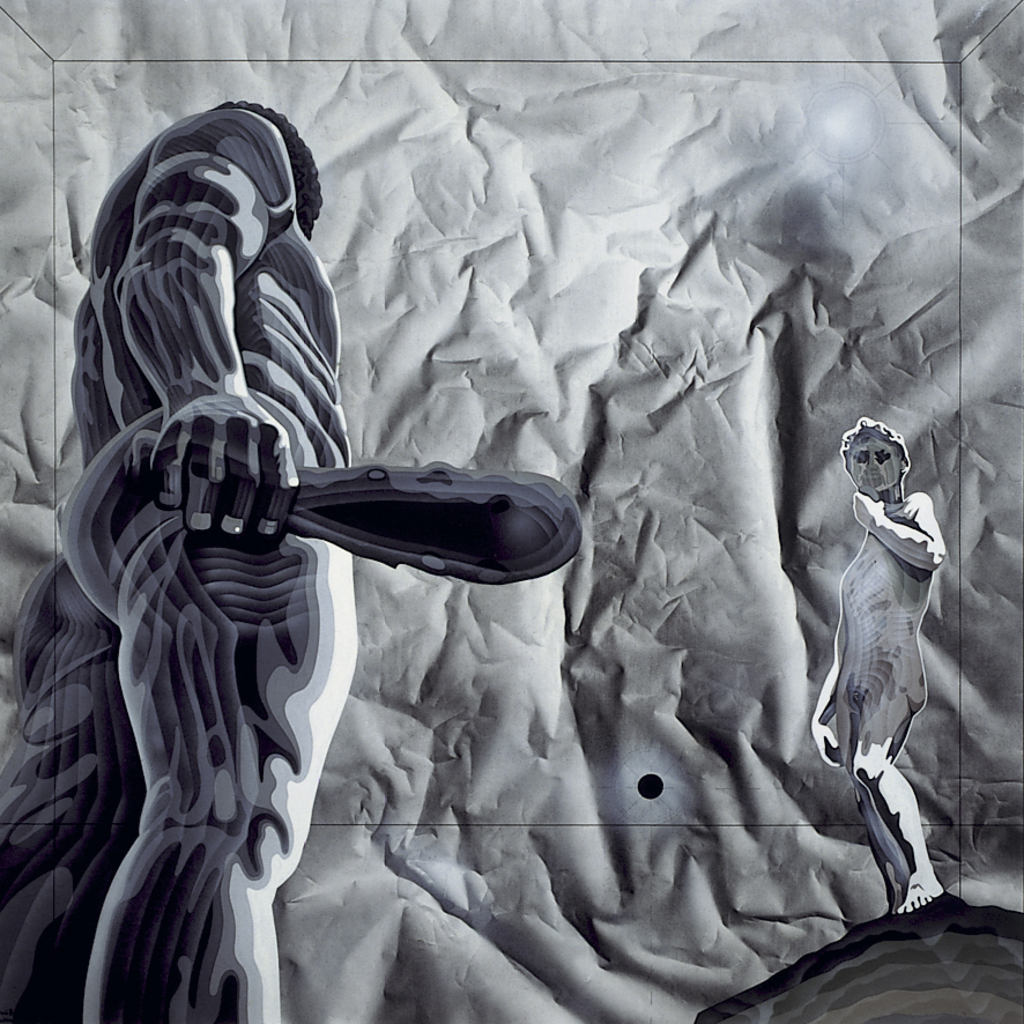

Herculusa and Daviet

In this work, Antoni Miró introduces the representation of two visions of the statues marking the entrance to the Old Palace in Florence: a replica of David by Michelangelo, and Hercules and Cacus by Bandinelli. Thus he draws on classical mythology but does so indirectly through the filter of Art History, through these two Mannerist works which epitomise the rivalry between the two sculptors and show off their different artistic qualities.

Painting sculptures forming part of the classical canon with a view to intentionally pursuing a different discourse is a way of paying homage to past artists, something which Miró developed a decade later with his Pinteu Pintura (Paint Painting) series. Furthermore, he uses these works in an ironic, decontextualised fashion, as is shown by his treatment of Hercules as a kind of Goliath who is seeking an opponent who will vanquish him.

Nevertheless, it is highly political, as was commonly the case in Miró’s works in the late 1960s and during the 1970s. It seeks to stage the conflict between the strong and the weak, lending support to the latter. The ruling empire, considered as the leading power, is embodied by the almighty Hercules, who appears feminised to make the reference to America clear. DaVIET plays the role of all the oppressed nations. It symbolises the hope that the latter may one day win. The passage of time is depicted by a sun bored in the canvas, whose movement can be guessed. It also seeks to show that the club wielded by Hercules is useless as a dominating attribute unless his foe is within striking distance.There is clear opposition between the foreground, occupied by HerculUSA, viewed from behind, and DaVIET’s position, farther away and higher on a mound in the field of perspective. The low-angle composition stresses the huge size of the first character. The power of his presence is further enhanced by the use of very dark grey tones to define the volume. By contrast, DaVIET is represented using a lower intensity range, closer to the original white. A drawn frame surrounds the four key elements in the image: the dominant club, DaVIET’s defiant posture, facing the sun on the horizon, triggered while defending himself and aiming at the right top, ready to shoot, which hints at the recurrence of the scene.

The two figures appear on a neutral, greyscale background that looks like paper wrinkled by the passage of time, giving a historical dimension to the work. The message the artist seeks to convey on imperialism is clear: the desire for liberation. Blasco Carrascosa noted that “Antoni Miró paints to be free... and to make us free”, insisting that this double dimension, individual and collective, “caters to a need: for liberation “from something” and “for something”. As Iglesias stated, this helps one grasp that Miró’s works form part of “the collective cultural unconscious” and that their communicative efficacy lies in the artist’s skilful use of “irony and even sarcasm”

Santiago Pastor Vila