Diàleg a tres (Three-way conversation)

In the ‘Paint Painting’ series, Antoni Miró expresses his criticisms and complaints using a repertoire that is shared and known by everyone, coming as it does from the art history canon. These “quotations and references” often allow his works “to stalk us” through “irony, metonymic play, covert metaphor, and the shock produced from the most straightforward comparison”, as Roman de la Calle puts it.

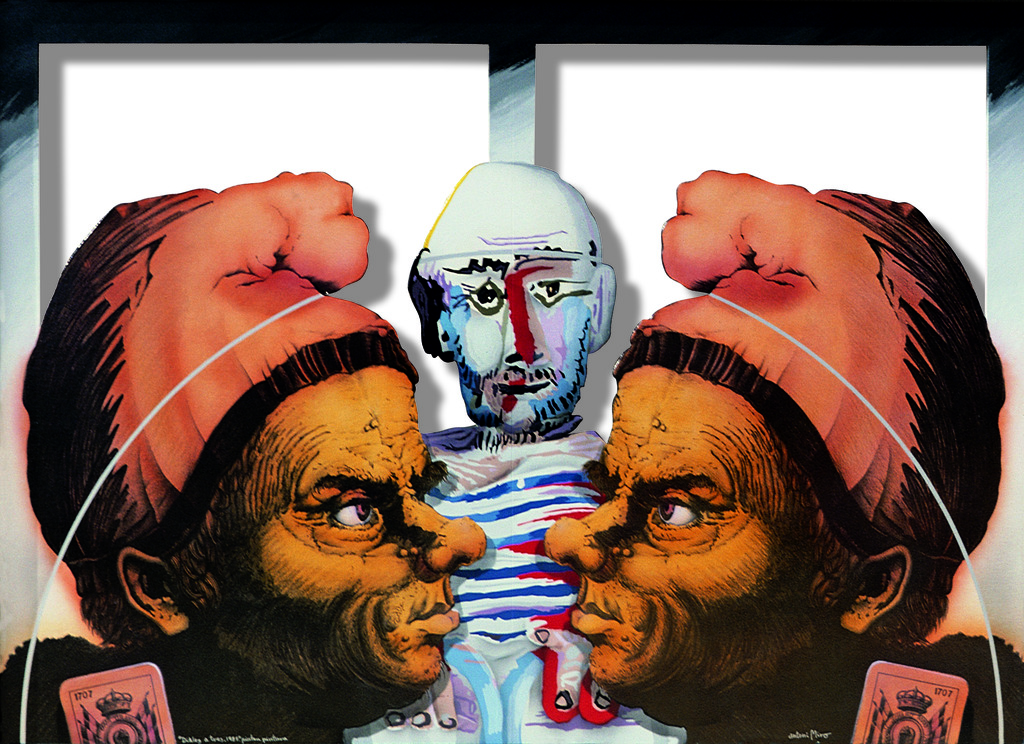

The title of the work refers to three characters, but in fact it is also the artist’s metaphor for the Catalan Lands’ place in Spain less than a decade after the instauration of the autonomous communities and the passing of their respective statutes. The metaphor reveals a Spanish Government that is oppressing these lands in two ways, thus failing to foster a more egalitarian relationship between them. Indeed, the incoherent terminological use of the word ‘dialogue’ is linked to the questioning of a real efficient communication, as shown by the silent speakers.

The three figures in the ‘dialogue’ are placed against a black-and-white background that mimics the frame of a figurative canvas. The artist depicts the true state of affairs hidden from our sight, hinting at a veiled situation, which stays out of sight behind the apparent but constitutes the key of the work’s fundamental purpose. The artist uses this composition to allude to negotiations in which only top politicians are involved, their deliberations being hidden from the citizenry. In other words, an apparent dialogue (revealed as a fiction by the silence of the three figures) which proves unequal at the same time (which is hinted at by the magnified presence of one of the agents).

As mentioned, three characters are obtained from only two references. One of them is a self-portrait of a mature Picasso. The other two come from the same drawing: a head study by José Ribera, which is coloured and duplicated symmetrically. The complacent gesture of the former contrasts with the stern looks of the two grotesque characters. There is also a contradiction between the loose, vivid colour strokes used by Picasso to show how he saw himself and what is nothing more than a morphological analysis of ugliness.

The situation is considered critical by the painter, and this must be effectively illustrated. In fact, the positioning of the figures seeks to create a visual tension through the direction of the gazes. The semicircle reinforces the idea of concentration on the same unresolved subject lying at this focus.

Some altered playing cards recall what the artist considers to be the origin of the problem, namely the centralisation policies undertaken by Felipe V in the early eighteenth century and which took the form of a series of Royal Decrees. One of these decrees was promulgated in 1707, and affected the old Kingdom of Valencia. That is why a kind of gold ace card is used to symbolise the Bourbon Monarchy, featuring the year 1707 and the slogan “One, Great.”

In other words, the artist uses two pictorial styles that are unconnected in terms of period, style, and purpose to identify a given situation through a certain representative unity (a pictorial collage) with a crystal-clear political purpose.

Santiago Pastor Vila