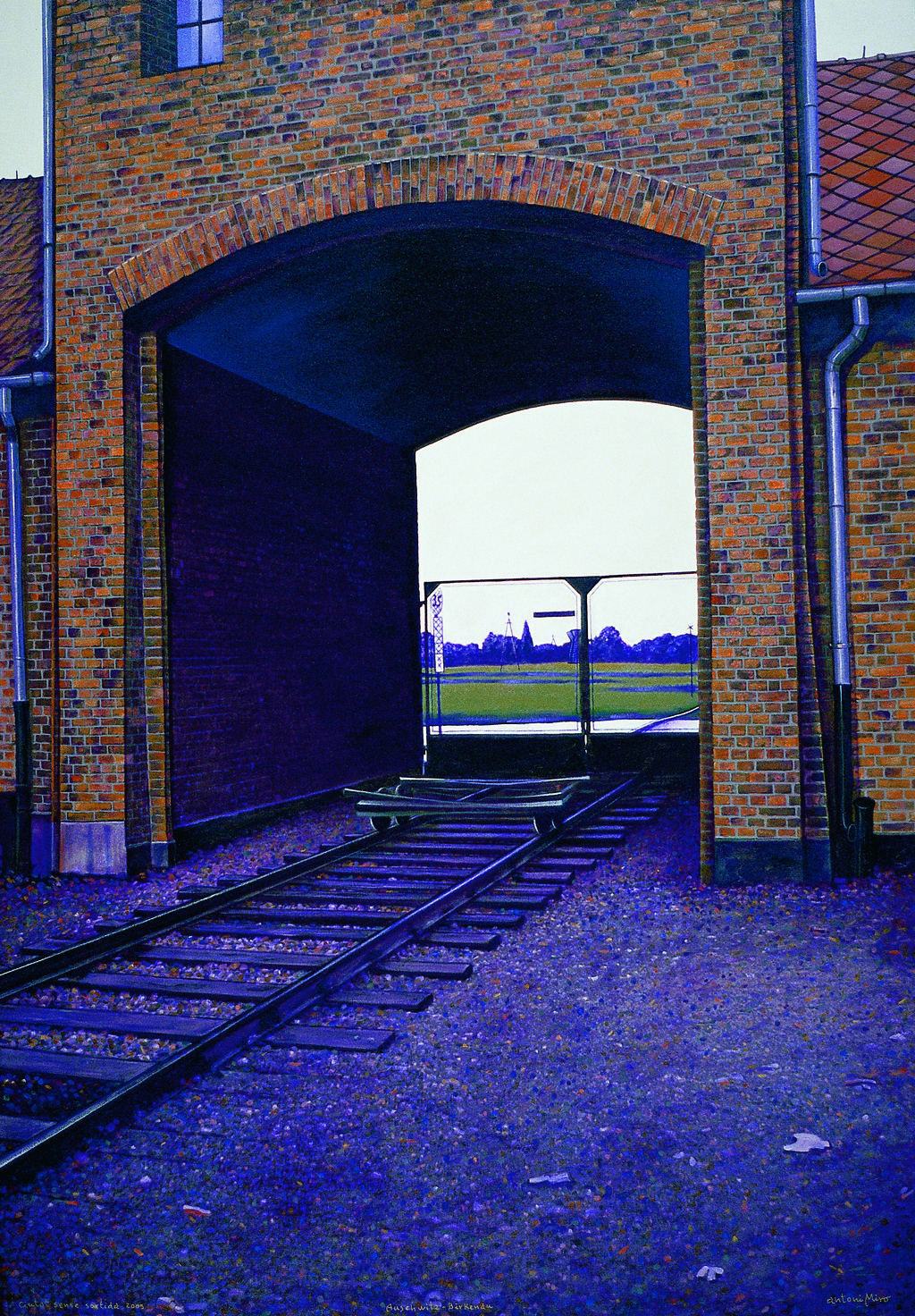

Ciutat sense sortida (Dead-end city)

Antoni Miró crafted this piece in 2005 — 60 years after the Red Army liberated the Auschwitz II-Birkenau concentration camp in Poland. Over 1,500 survivors of the camp attended the commemorative events that year. A decade later, however, only a few more than 300 were able to do so. Auschwitz and all it represented will soon pass out of living memory.

It made perfect sense that this place and the buildings and infrastructures should be turned into a museum in 1947, shortly after the war’s end. That is because the place has served as a symbolic monument and a primary documentary reminder, and will continue to do so in the future. Despite the apparent contradiction, showing the context of the 20th Century’s most despicable fact (the genocide of Jews and other minorities in Central Europe living under Nazi rule) is an act of civilisation.

Painting a work that both reflects the absence of life and conveys a stark terror is a task that is inspired by the same principles. Neither the place nor Miró’s work depict and cherish what is beautiful and valuable but rather evoke Mankind’s most appalling crimes. Nothing can heal the wounds caused by the death and suffering of over a million people at Auschwitz. The Holocaust was painstakingly planned by the Nazis and its goal was to be definitive — the Third Reich’s ‘Final solution to the Jewish question’. The horror produced by our remembrance of it is made all the greater when we consider that its architects considered it a ‘solution’. It was not so, but for sure it was ‘final’. Those who died there include millions of Jews, Poles, Gypsies, and other nationalities and minorities, including Spanish Republicans. They were exterminated in camps that promised freedom through forced labour, as the slogan over the camp gates said — Arbeit macht frei [Work makes one free].

This takes us to the ‘dead-end’ nature of this city. The use of the word ‘city’ is not a coincidence. Miró calls Auschwitz that because of the sheer size of the place, its structured organisation and the fact that its denizens partake of the same fate, all of which are features found in cities. Yet many of Auschwitz’s other features are starkly at odds with a city, namely the lack of freedom and its condition as a prelude to death. This is a terrible newly-built ghetto that had little of the security measures found in the prisons of the time, as the weakness of the victims and the haste with which they were murdered made them unnecessary.

The nature of this ‘dead-end city’ is hinted at by the railway tracks that reach the gate, with no continuity solution. None of the hundreds of modern-day visitors who flock to the camp are shown because the idea is to show the place as one inimical to life. Only the passage of time is suggested by the pile of gravel on the sleepers. A broken trolley car on the tracks symbolises the impossibility of passing through the gate out of the camp.

Clearly, no one can keep the memories of such appalling deeds alive. Yet what one can do is to strive (as Miró does) to ensure that these horrors will not be repeated by showing the unbearable unrest still produced by this place. This surely is the best homage one can pay to the victims of the Holocaust.

Santiago Pastor Vila