Antoni Miró’s, ethical implication

Pasqual Patuel

Antoni Miró (Alcoi, Alacant, 1944)1, former member and alma mater of Grup Alcoiart2 -created in 1964- has always defended a critical artistic stance vis-à-vis the surrounding society, developing a strong ethical implication in which he brings into play a Pop vocabulary. First in his relation with that artistic group, and later in his individual career, he has put his creativity at the service of a process of raising public consciousness of the existing imbalances in our contemporary society.

The objective he has maintained throughout his artistic career is replete with this critical outlook towards the culture of the time, contributing with revisionist patterns aimed at promoting a change of focus towards new possibilities. With that purpose in mind, Miró has developed a comprehensive iconography which ranges from irony and sarcasm to the subtlest tenderness. His painting no longer evolves within a bland and neutral plane, but it brings with it a strong provocation aimed at provoking in the spectator a capacity for reflection on the context they live in.

Stemming in these premises, Antoni Miró’s ample production has articulated, in one series3 after another, all his proposals with the clear intention of emphasising all those situations of social imbalance and injustice affecting human beings. His analysis is grounded in a number of immediate and well know events in what amounts to a sort of critical chronicle of recent historical occurrences. In this sense, Joan Ángel Blasco says:

“He has recorded the violation of human rights, the same of racism, the horrors of war, the always problematic concern of social emancipation, the alienation based on myths, individual and collective miseries, the violence provoked by fascist savagery, the progressive dehumanisation of contemporary man, the different and varied systems of manipulation, the desire for national and cultural independence, the dangers of military imperialism, the dependencies derived from an aggressive capitalism, the never dying hope for a fairer and freer world.4”

Landscape as a theme has been overly abundant in Miró’s oeuvre at the beginning of his artistic trajectory in the early 1960s. On the other hand, it is the human being subjected to the most adverse circumstances that has polarised his interest and attention. Sometimes we find landscape as a compositional background or in his quotation of other painters, such as Salvador Dali or Joan Miró.

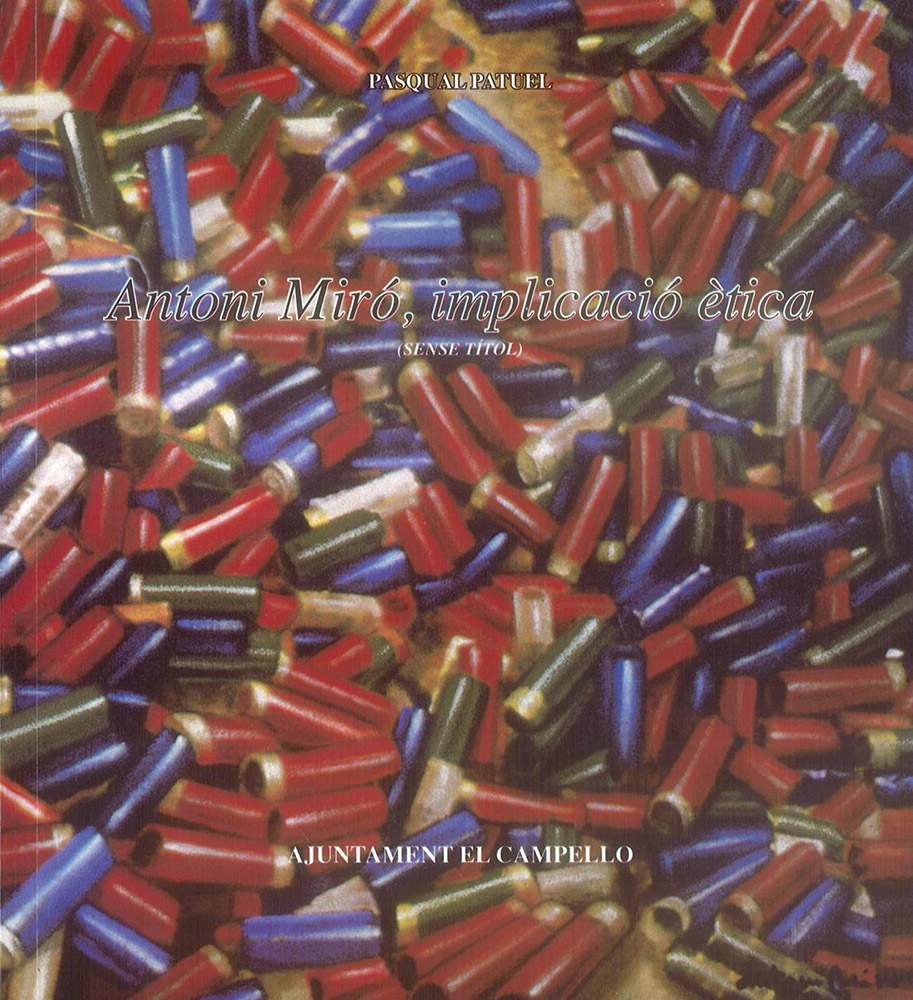

This tendency, however, underwent a sharp turn in 1991 with the beginning of a series generically entitled Vivace. In it, his gaze focused on the natural environment where human life is played out, within an eminently ecological approach underlining all man’s environmental abuse of the forms of life in that common sphere. Uncontrolled dumping, deforestation, pollution of the subsoil, industrial waste, in short, the exploitation of the Earth for speculative purpose focus the attention of this series where landscape underlies the end proposal.

Far from being a mere re-enactment of natural beauty, landscape here sound the alarm about current attacks on the environment, at the same time promoting a way of life more in harmony with nature, the source of all life. Miró evokes a lost paradise to whose humankind must head, where material progress should not be incompatible with the preservation of the ecosystem. His sometimes apocalyptic works are future visions of a situation which may come true, yet always with the intention of provoking reflection and redirecting human behaviour towards the cosmos.

The human being’s power of destruction strongly contrasts with the blue of his landscape. We could perhaps detect in Miró’s works an Eros-Thanatos, life-death, element in the specific way he approaches the environment, from a dialectics of opposites which regards man’s devastating action in confrontation with the beauty inherent in nature. In this sense, his works invite us to enjoy them and to reflect on the consumerist society with the idea of making possible the birth of a new approach to man’s relationship with nature. As Josep Lluis Peris writes:

“Nature seems to be defenceless and despised by the arrogance and self-importance of the artefacts created by man’s technological reason. These objects acquire a monstrous dimension, inverting and transformative dimension, inverting in front of the spectator’s gaze their mechanical, logical and transformative function on the environment, in such a way that a digger, a heap of industrial waste, or a rubbish container are treated by the painter’s hand as truly symbolic exponents of the devastating and anti-natural intervention of contemporary man over the environment5”.

1. Wences Rambla, Forma y expresión en la plástica de Antoni Miró, Alacant, CAM, 1998.

2. Román de la Calle “Grup Alcoiart: 1965-1972”, en cat. exp. Art-Sud, Caja de Ahorros Provincial de Alicante, 1988.

3. La Fam (1966), Els bojos (1967), Vietnam (1968), L’home avui (1973), Amèrica Negra (1972), El dòlar (1973-1979), Pinteu pintura (1980-1989), Vivace (1991...).

4. Juan Ángel Blasco Carrascosa. From the introduction that headlines the book of Joan Guill, Temàtica i poètica en l’obra artística d’Antoni Miró (1965-1986). UPV Ajuntament d’Alcoi, València, 1988.

5. Josep Lluis Peris, “Vivace: una visión ecosocial”, en cat. exp. Antoni Miro, Castelló, Bancaixa, Centre d’Exposicions Sant Miquel Centre Cultura Casa Abadía, 1998.