Antoni Miró

Olexander Butsenko

“Fin de siècle"— fin de siglo, esa combinación de palabras entró sólidamente en el diccionario de la cultura europea determinando un fenómeno que se creó a finales del siglo XIX y obtuvo en distintos países los nombres distintos —moderno, secesionista, modernismo, Art Nouveau, jugendstil, liberty. El fin del siglo XX es rico también en términos como neofigurativismo, neoexpresionismo, transvanguardia, arte social, que al fin y al cabo expresan las búsquedas generales del arte al reflejar los complicados fenómenos históricos y sociales. Sin embargo los acentos en el panorama del arte ahora han cambiado. Si a finales del siglo XIX además de Antoni Gaudí con sus asombrosas edificaciones artísticas, los representantes del modernismo artístico en Cataluña eran pocos, más tarde la influencia catalana en las corrientes modernas de las bellas artes europeas se hizo visible e importante y sigue siéndolo hasta hoy en día. Entre los pintores catalanes del final del siglo XX se distingue el nombre del pintor valenciano de la ciudad de Alcoi, Antoni Miró.

Hay un proverbio que dice que el talento es la vocación multiplicada por la labor, y que es aplicable tanto a una persona como a un pueblo. La significación y la gloria de la “región autónoma de Cataluña” reside exactamente en este factor. La vocación de Cataluña, en su significado histórico y cultural, es su situación mediterránea, su existencia en la órbita de aquella cultura que influyó profundamente en la vida de Europa; con todo ello Cataluña hizo su aportación original, como por ejemplo con la mayólica1 o la mayonesa ligadas directamente al nombre de la isla catalana de Mallorca. La originalidad de la vocación histórica de Cataluña o de los Países Catalanes se inicia en sus raíces ibéricas que ascienden a los tiempos del paleolítico, exactamente de entonces datan las cuevas con restos de la cultura primitiva, con las inscripciones de un idioma que parece estar escrito con letras griego cirílicas. Los mismos topónimos de Ibi y Tibi demuestran esos antiguos vínculos. Así como Cetabis (Xàtiva), Valentia (València) y Alcoi testimonian las influencias romanas y árabes. Desde los tiempos medievales se ha conservado una fiesta basada en acontecimientos del siglo XIII relativos a la conquista de la ciudad por las tropas cristianas. El día de San Jorge es la fiesta local en muchas ciudades catalanas, y en particular de Alcoi. En el Museo de la Fiesta se exponen trajes tradicionales y muchos objetos relacionados con esta celebración anual, entre los cuales se encuentra alguna obra de Antoni Miró.

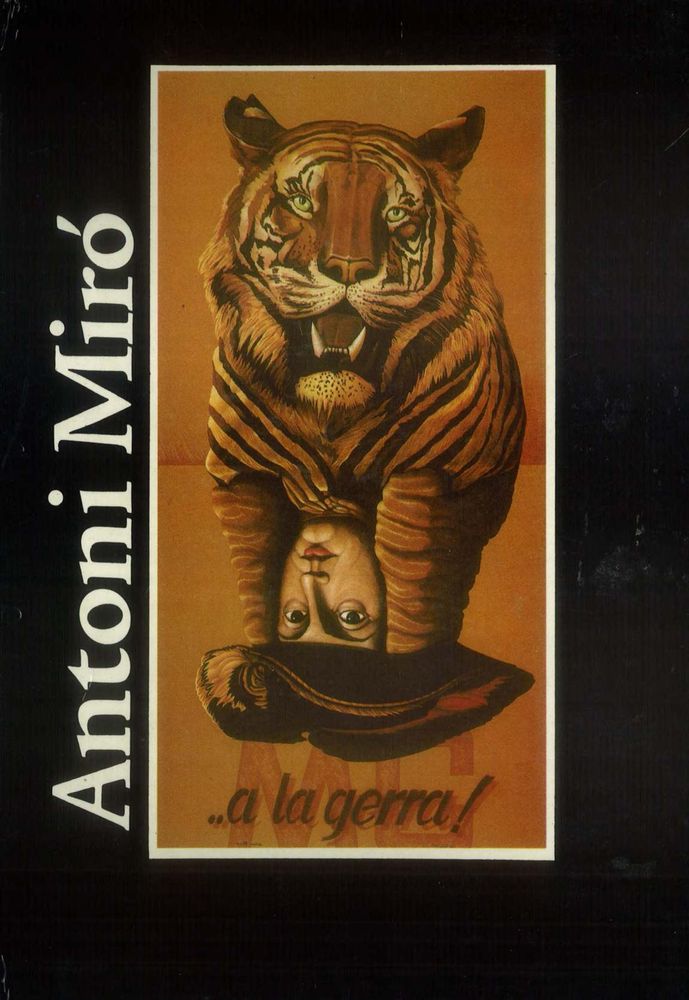

La laboriosidad de los catalanes la confirmaron no solo los navegantes y los pescadores de esta región, sino también los campesinos, que pudieron desarrollar en los lugares montañosos una agricultura con productos conocidos en todo el país, los artesanos los joyeros... El talento de los Países Catalanes lo demostraron filósofos destacados como R. Llull; escritores como J. Martorell y J. de Galba; pintores como J. Ribera... Pero lo mismo que cualquier nación sabia situada estratégicamente en la encrucijada de caminos históricos, económicos y culturales, los catalanes tuvieron que defender su libertad y su idiosincrasia durante toda su existencia. Sin mirar demasiado atrás, señalemos que durante más de dos siglos y medio Catalunya ha estado privada de su independencia nacional. Esto sucedió a consecuencia de su anexión por el rey de Castilla Felipe V, en 1707. Esta fecha se grabó en la memoria de los habitantes de Cataluña. Felipe V impuso el decreto de “Nueva Planta” que prohibía, entre otras muchas cosas, emplear el idioma catalán. Estas prohibiciones decretadas por el rey funcionaron de una u otra forma hasta finales de los años 70 del siglo XX, cuando Cataluña obtuvo la autonomía y fue aprobada una ley autorizando el uso de su idioma nacional. Claro que el nombre de Felipe V goza de mala fama en Cataluña. Por eso al proclamarse la autonomía, en el museo de Xàtiva, patria de J. Ribera, colgaron el retrato de Felipe V al revés, patas para arriba, y así está hasta hoy. Esto explica el cuadro de A. Miró “Felí-Felip”, del mismo modo que los detalles históricos mencionados anteriormente explican muchas alusiones pictóricas de A. Miró. El mismo nombre del cuadro se compone de dos partes: “Felí” —del latín “felidae”, que quiere decir proveniente de la clase de las fieras felinas—, visualmente corresponde al tigre situado en la parte superior del cuadro; “Felip”, es el nombre del propio rey, cuyo retrato del revés está acompañado del llamamiento invertido “a la gerra!", en el que “gerra" en catalán quiere decir “olla” en vez de “guerra”. La ironía de la obra se acentúa con el empleo de la técnica del op-art: las rayas de la piel del felino se entrelazan con las rayas de los bucles del rey dando la imagen de la esencia del monarca español.

La conciencia nacional de los intelectuales catalanes no sólo se ha formado a través de la memoria histórica, sino también mediante la propia experiencia cotidiana llena de humillaciones y ofensas a la dignidad nacional. Antoni Miró recuerda que cuando empezó sus clases en la escuela conocía mal el castellano, porque solía hablar en su casa en catalán; pero el maestro le prohibió hablar ese “idioma vulgar”; otra gente llamaba al catalán “el ladrido del perro”. Todo esto sucedía no hace mucho tiempo, en los años 50.

Antoni Miró nació en 1944 en la ciudad de Alcoy. Esta antigua ciudad valenciana fue famosa por sus artesanos y maestros en producir papel, tejidos, etc. También en la familia del futuro pintor apreciaban mucho el trabajo manual: su padre era herrero, su madre fue modista. Es correcto decir que Antoni Miró heredó la laboriosidad de sus padres: trabaja de 12 a 14 horas diarias y a veces más. Su vocación la descubrió en la infancia: todo el tiempo libre lo dedicaba a su labor preferida, la pintura. El trabajo en el taller de su padre le ayudó a conocer muchos materiales modernos y la naturaleza de las pinturas lo que contribuyó a sus hallazgos artísticos. La base artística se la dio su único maestro, el pintor local Vicente Moya, bajo cuya dirección A. Miró aprendió “la escuela”, conociendo los géneros tradicionales: el retrato, el paisaje y la naturaleza muerta. Estos primeros trabajos con cierto matiz académico expuestos en el concurso de pintura de Alcoi en 1960 le dieron a Antoni Miró el primer premio del Ayuntamiento de la ciudad. Pero con esto se puede decir que terminó el período preparatorio, ya que la observación diligente de los cánones, el conservadurismo académico y los métodos de salón eran ajenos al joven pintor.

Los años siguientes los dedica A. Miró al dominio de una línea estilizada y muy expresiva, a la precisión del dibujo y a experimentar con los colores. Participa con éxito en sucesivos concursos en Alicante, Madrid, Valencia..., pero antes de inaugurar su primera exposición personal en 1965 hace dos cosas importantes: crea la primera serie de “Les Nues” (1964) y funda el grupo de pintores de Alcoy denominado “Alcoiart”. Estas dos cosas son relevantes para comprender en general la obra de Miró. Su primera serie artística reunió los trabajos de pintura realizados de manera tradicional: lienzo, óleo, dibujos (no bocetos para la pintura), grabados y aguafuertes clásicos con las líneas profundamente marcadas; unidos por una idea y un tema comunes. Una aspiración semejante hacia la autorrealización en distintos tipos de las artes plásticas es propia de muchos artistas del siglo XX; en particular de los representantes de la vanguardia española: Picasso, Dalí, etc. Pero este universalismo refleja, casi siempre, la calidad polifacética y la potencia creadora de la naturaleza pictórica y no la variedad expresiva de las formas del mismo tema o de la misma idea como sucede en las series de A. Miró2.

Los pioneros del estilo moderno, aun aspiraban, a finales del siglo pasado a la síntesis ideal de las distintas artes. Este sueño, “la alianza de las obras de distintos tipos de arte en un todo único”3 lo llamó R. Wagner en su tiempo “Gesamtkunstwerk” y lo intenta realizar a su manera A. Miró agregando en las series siguientes obras de cerámica, escultura, monumentalismo, pintura-objeto, etc. La idea de la unión conceptual de distintos estilos de distintas artes fue en gran medida la base de la creación del grupo “Alcoiart” que existió hasta 1972 y empezó su actividad exactamente con la inauguración de la primera exposición personal de A. Miró. En fin, la inclinación a la síntesis se manifestó también en la utilización indirecta de muchas artes cercanas: poesía, música; ediciones de libros y catálogos incluyendo poesías de escritores conocidos como R. Alberti, S. Espriu, P. Serrano, J. Fuster...; de actores como A. Gades, O. Montllor, escritas bajo la influencia directa de las obras de A. Miró, se manifiesta como Gesamtkunstwerk —producto de la creación de sus correligionarios—.

A finales de 1965 tuvo lugar en Monmartre (París) una exposición informal de A. Miró. Desde entonces varias veces al año las obras del pintor se exponen en España y en muchos países del mundo sin contar numerosas exposiciones colectivas en que participa. A finales de 1990 los habitantes de Ucrania vieron por primera vez grabados de A. Miró; la exposición de sus obras se inauguró en Kiev y durante 1991 se exponía en Ivano-Frankivsk y Lviv. El mismo año de 1991 el pintor vino a Kiev como miembro del jurado de la II bienal “Impreza-91” en Ivano-Frankivsk.

En la segunda mitad de los años 60 A. Miró creó las series “La Fam” (1966) “Els Bojos” (1967), “Vietnam” y “Mort” (1968—1969). Este período en la obra del pintor lo determinan los críticos de arte como el trayecto “del expresionismo al neofigurativismo social”4. El expresionismo de A. Miró tiende también a la síntesis, en este caso a la unión de las épocas. La acentuación grotesca de los defectos exteriores detrás de los cuales se esconde una imperfección espiritual (Bosch, Brueghel); un interés hacia las escenas conflictivas que desfiguran las facciones de la persona (A. Brauer), en particular los lienzos cuyo tema son distintas peleas; la investigación de la naturaleza de lo repugnante (J. Ribera) (a una de las imágenes de Ribera —se trata del retrato de medio cuerpo del viejo repugnante “La cabeza del mutilado” (1622)— recurría más tarde A. Miró muchas veces); el reflejo de los horrores del tiempo (F. Goya, “Caprichos”); el grito de la desesperación (“El grito” de E. Munk, las obras de E. Nolde). Todas estas analogías brotan debajo de las “abultadas” pinceladas de la serie “Els Bojos”. El pintor intenta a través del material expresar su sentimiento interno — las imágenes obtienen los rasgos exagerados, alegóricos.

Después en la serie de “Relleus visuals” (1968-1970) aquellos rasgos desaparecen por completo dejando solamente la pulsación de los colores, la tensión del relieve y las determinaciones espirituales. En escultura, A. Miró trabaja en aquellos tiempos con bronce, hierro y aluminio dando al material una plasticidad expresiva y organizando el espacio de tal manera que todas las prominencias y cavidades componen una imagen sintética como si volviera del revés el objeto. En este sentido las búsquedas del pintor tienen cierta semejanza con las búsquedas de R. Duchamp-Villon, O. Arjípenko, A. J. Adam, etc. Pero estos métodos y materiales tradicionales, asimilados por el siglo XX ya no satisfacen al pintor de Alcoi cuyo rasgo distintivo es el desarrollo continuo, el movimiento, la búsqueda. En pintura, A. Miró renuncia por completo al óleo recurriendo a las pinturas acrílicas descubiertas en 1940 y a nuevos métodos técnicos como el aerógrafo. En escultura, utiliza materiales nuevos: poliéster y sustancias sintéticas. Une la escultura y la pintura en las obras “objeto”.

Esta modernización de la tecnología influye, sin ninguna duda, en la metodología creadora también. La resonancia de los colores, la apertura emocional de la pintura abstracta ya no podían satisfacer al pintor. Sintiendo total y concretamente la injusticia del mundo en que vivimos él quiere que el espectador la experimente también. Las series de A. Miró de finales de los años 60 y 70 son invocaciones conscientes al figurativismo subrayado, porque exactamente a través de la imagen real se consigue la unión de lo sensitivo y lo razonable. Los críticos determinaron justamente estas obras de A. Miró como “el realismo social” y escribieron, en particular: “Antoni Miró no sólo pinta la realidad tal como es, sino a la vez expresa su deseo de pintor de cambiar esta realidad”5. La posición social del pintor se apoyaba en las opiniones de los “hombres enfurecidos” y en las convicciones inconformistas que impregnaba a la filosofía y la literatura europeas en los años 50 y 60 que desembocaron en los movimientos estudiantiles de 1968.

En 1972 A. Miró junto a varios pintores italianos crea en la ciudad de Brescia (Italia) el “Gruppo Denunzia”. Las exposiciones que el “Gruppo Denunzia” mostró en los países europeos representaron un acto de protesta de los pintores contra cualquier humillación de una persona o de una nación. En el fundamento de esta posición estaban las ideas socialistas compartidas ahora por mayoría de los pintores europeos.

Las opiniones socialistas de A. Miró, libres de la ideología dogmática y de los secretos partidistas, de la utopía inocente o del cuartel encontraron reflejo tanto en su posición creadora, como en su posición vital.

Estando en Ucrania él dijo que si hubiera vivido aquí, seguramente lo hubieran deportado a Siberia. Sin dudar A. Miró hubiera compartido el destino de los intelectuales ucranianos que en los años 60-80 entraron en los campos de concentración, cárceles y emigración. El pintor de Alcoi hubiera resultado indeseable para las estructuras del poder, por su protesta activa acertada y mordaz contra la injusticia, lo que se reflejó en sus trabajos de las series de los años 70. Son las series “Realitats” y “L’Home” (1970-1971), "Amèrica Negra” (1972), “L’Home Avui” (1973), “El Dòlar” (1973-1980) que incluyen las subseries “Les Llances”, “La Senyera”, “Llibertat d’Expressió” y “Xile”.

Las imágenes reales en los trabajos de las series antes citadas están privadas, de un lado del naturalismo propio a la corriente realista y de otro lado — de la estilización estética que acerca inevitablemente la pintura figurativa al idioma del cartel. A. Miró construye sus obras como un gran decorado cinematográfico, en el que el fondo constituye una continua masa mono crómica, todo lo excedente se trunca y los detalles insignificantes tienen gran importancia semántica. Por ejemplo, en las obras “Vietnam” (1972) y “Desesperança” (1973) se utiliza el efecto del marco doble, mientras el argumento principal está construido con una cadena de figuras humanas (continuando la analogía del cine: cuadros repetidos en el celuloide). En el primer caso es un soldado con muletas: el futuro que espera al invasor, que en el argumento central acerca la pistola a las sienes de un soldado prisionero vietnamita, y en general —las consecuencias de cualquier guerra. En el segundo caso es una figura de la persona que no tiene fuerzas para perforar el muro: son consecuencias casuales de la desesperación siguiente. En otras obras el argumento tiende a la repetición, al reflejo, a la fracción en episodios sueltos, al contraste de dos mitades. La utilización artística del estilo del pop y op-art, la metaforización de las nociones y los sucesos de la historia actual convierte las obras en pictóricamente expresivas, activiza el enlace invertido espectador-cuadro-pintor a través de la comprensión y la compenetración.

Igualmente en la escultura de aquel período A. Miró vuelve a la objetividad real. Transmitiendo la integridad a través de lo parcial (y de este modo remitiéndose a la comprensión de la armonía por los representantes del Renacimiento) A. Miró crea sus “manos”, “pies” y “torsos” sin el exotismo de los modernistas, sin la disección de los vanguardistas o el naturalismo de los realistas. Es más bien la tradición antigua adaptada a la contemporaneidad. Hasta en las esculturas como “L’Home del capell” (1974) y “L’Home de casc” (1974) está reflejada en primer lugar la tradición antiguo-griega de las imágenes plásticas en la forma del falo. Verdad es que los atributos modernos —el sombrero y el casco— dan a estas imágenes una interpretación freudiana y cierta ironía.

Con su subserie “Les Llances” creada a finales de los años 70, A. Miró se acerca directamente a una de sus series centrales “Pinteu Pintura”. El precedente de esta serie fue su obra de 1968 “Les Tres Gràcies” donde las diosas mitológicas que representan en sí mismas el inicio eternamente joven de la vida, buena y alegre, cambian completamente en las condiciones contemporáneas y adquieren otro contenido de acuerdo con las exigencias de la sociedad. Dos indicios principales de la serie “Pinteu Pintura” (1980-1991) en los que ya se observa su antimitologismo e ironía. Hablando con propiedad el mismo nombre está lleno de negación mutua o de importancia irónica. A la vez, en la serie “Pinteu Pintura” se encarnó más completamente la síntesis propia de A. Miró —la unificación de las épocas y los estilos: los maestros de todos los tiempos y de todos los pueblos aparecen agrupados bajo el techo de una concepción y una corriente creadora. Es lo mismo que si el pintor de Alcoy pudiera juntar un colectivo brillante de intérpretes y pudiera unir en resonancia armónica los instrumentos musicales medievales con los más modernos actuando como director y primer violín. Entre paréntesis, si se trata de la música, hay que decir que la serie en la cual trabaja ahora se distingue por completo de las anteriores y tiene el título de “Vivace” —término musical que significa “interpretación animada”— y está dedicada a la ecología en el sentido más amplio de la palabra.

El antimitologismo y la ironía de la serie “Pinteu Pintura” son las dos caras de la misma moneda. Sobre la significación de los mitos en la vida de la sociedad y de la persona escribieron C. Marx, M. Bloc, A. Lociev y muchos otros filósofos e historiadores. Renunciando a unos mitos intentamos en seguida crear otros, tanto en el sentido histórico como en el sentido social, creador y cotidiano. En la serie “Pinteu Pintura” A. Miró destruye el sistema inmutable de los mitos sin crear con todo esto una mitología nueva a la que tendían todas las corrientes de las bellas artes del final del siglo pasado y durante el siglo en curso. Pero éste acto destructivo no tiene —y es una paradoja— carácter nocivo. Destruyendo los mitos el pintor no priva al espectador de apoyo interior, al contrario, le regala la libertad espiritual y hace más alta su esencia humana.

El destronamiento del mito histórico-heroico y de la consciencia ligada con él se dan en la subserie “Les Llances” creada en base del famoso lienzo de Velázquez “La rendición de Breda” (1634-1635) que tiene también otro nombre “Las lanzas” y refleja un episodio real e histórico, la rendición de la ciudad-fortaleza de Breda y su guarnición a las tropas españolas. Son conocidas las palabras del distinguido poeta Luis de Góngora, contemporáneo de Velázquez: “A Breda la rindió el hambre”. El mismo lienzo de Velázquez pintado después de los acontecimientos de 1625 está cubierto con el velo heroico-romántico y representa la escena central de la entrega de las llaves de la fortaleza por el adalid flamenco J. Nassau al español A. de Espínola, lo que simboliza la dignidad de los vencidos y la nobleza de los vencedores. Sin embargo, como testimonian los documentos históricos cuando los españoles ocuparon la fortaleza encontraron allí reservas de pan para un mes y de vino para tres meses. Es por eso que A. Miró subraya los intereses corrientes y ávidos — los de compraventa (lo que al fin y al cabo están en la base de todas las guerras, grandes y pequeñas) y no los heroicos del episodio histórico; el pintor lo subraya en las variantes más distintas de la serie: en una de ellas el aguafuerte “Les Llances” (1975) los dos ejércitos enemigos están armados ya con misiles y tanques. Con todo esto señalemos que el ejército español, como tal, se llamaba entonces “Las lanzas del imperio”, porque se componía principalmente de mercenarios.

Esto, inconscientemente se le ocurre a uno cuando entra en el espacio del lienzo de Velázquez penetrando a través del tiempo —en el sentido directo e indirecto; la pintura-objeto de A. Miró “Llances imperials” (1976-1977) le da la posibilidad a uno de convertirse en participante del período histórico.

El estudio de la temática de Velázquez6 le permite a A. Miró destruir no pocos mitos o reinterpretarlos irónicamente. Por ejemplo, el mito sobre los valores sociales. Lo que compone el orgullo de los contemporáneos lo expresó Homero en la conocida lista de los barcos; Bernal Díaz del Castillo en la enumeración de los caballos7 llevados a la Nueva España y A. Miró en las marcas de las compañías automovilísticas que adornan la grupa del caballo del Conde Duque de Olivares de Velázquez “Retrat Eqüestre” (1982-1984).

En 1932 Marcel Duchamp en la exposición de las obras de A. Calder introdujo el término “móviles” para las esculturas del artista americano. Entonces nació una literatura que investiga el descubrimiento del espacio tridimensional hecho por Calder, en el que sus construcciones móviles reaccionan a la agitación del aire y pueden existir como un sueño estereoscópico sólo. Pero A. Miró somete a la ironía este mito también. Puesto en “El jardín de las delicias” de Bosch “Jardí amb mòbil” (1987) el móvil de Calder no pierde el sentido tridimensional, pero a la vez se enriquece a través de un enlace asociativo e inesperado.

Las imágenes de pop-art de Roy Lichtenstein sacadas de los comics se consideran muy comprensibles para las masas de espectadores porque son sangre de la propia sangre de la cultura de masas. Pero en el cuadro de A. Miró “Ràtzia” (1987) el avión de caza supersónico de los comics de Lichtenstein encima de los personajes de Goya luce amenazador tanto desde el punto de vista de las armas de destrucción masiva como desde el de la cultura agresiva de masas. Como es sabido, empezando por transferir los personajes de comics al plano del arte R. Lichtenstein terminó en el proceso inverso. Y uno de los sentidos del cuadro “Vetllaire” (1987) da a entender esto, indicando las distintas fuentes de las imágenes de los mass-media-academicista en forma del gallo muerto.

En general, las obras de la serie “Pinteu Pintura” están marcadas con una amplia polisemántica y pueden entenderse en distintos niveles y bajo distintos puntos de vista. El enlace lineal de las series anteriores autor-cuadro-espectador, se complica en ésta serie con la ayuda de un sistema de espejos en los cuales se reflejan multiplicándose constantemente no sólo las alusiones, evidentes o escondidas, analogías y detalles simbólico-culturales, sino también nuestro propio entendimiento, el nivel de nuestra enseñanza, el grado de la sensibilidad. En una palabra, resulta que nosotros mismos nos encontramos en aquel laberinto de espejos y mirándolo observamos nuestra propia cara.

La Iconografía de la serie “Pinteu Pintura” no es sólo la unión de las imágenes de los artistas de distintas épocas, sino en primer lugar de los representantes de distintos estilos y corrientes cuyas fronteras parecían inquebrantables.

El retrato de Carlos V de Tiziano “Carlos V en la batalla de Mölberg” (1548) se transforma con la técnica de la litografía y adquiere rasgos de una marca comercial “Cromo de Carlos V” (1988-1989). El mismo retrato de Carlos III realizado por el pintor alemán A. Mengs se encuentra ahora en Nueva York “Un rei a New York” (1987), ahora en París “Un rei a París” (1987), cambiando de acuerdo con el medio ambiente. Los participantes de “La fiesta de verano” de D. Teniers (1646) festejan lo mismo —sea la invariabilidad del arte viejo, sea la aparición del nuevo lo que aparece en el fondo con las imágenes de V. Kandinsky. El personaje de Gauguin rodeado de una decoración taitiana escruta con la mirada los contornos mediterráneos en los cuales rezuman no los símbolos de las creencias primitivas de los aborígenes sino las imágenes simbólicas de P. Klee y Z. Miró en “Mediterrània” (1988). Todo esto lleva a comprender que las definiciones y esquemas del arte tienen un carácter relativo y en cierta medida “mitológico”, los límites entre ellas son temporales y en la mayoría de los casos inventados y a veces las corrientes aparentemente muy lejanas resultan tener los enlaces directos. Por ejemplo, en el cuadro “Translúcid” (1986-87) fuera de la vidriera geométrica de Mondrian rezuma el anciano de J. Ribera antes mencionado. La metafísica de G. de Chirico se inserta orgánicamente en el “Jardín de las delicias” de Bosch. En el cuadro “Arístide esguardant a Gala” (1988) la imagen principal es el dueño del café concierto Aristide Bruant personaje de Toulouse-Lautrec. Siguiendo su mirada escudriñamos “el cuadro en el cuadro” que es el retrato estilizado de la esposa de Salvador Dalí. Pero Artístide Bruant en nuestra consciencia es imaginado, hablando con propiedad, por su creador Toulouse-Lautrec. Quiere decir que el mismo Lautrec con una sonrisa irónica mira los frutos del Arte Nuevo. O más exactamente nosotros junto con Lautrec miramos y comparamos... Nos movemos por la galería de espejos de las imágenes del arte que los academicistas y los vanguardistas hacen igualmente en “La fragua del Vulcano”, ya que en el yunque están derramadas inconscientemente las visiones de aquellos. No en vano el crítico de arte valenciano Romà de la Calle determinó la serie de A. Miró “Pinteu Pintura” como “la consciencia de la pintura”8.

Como regla, los títulos de las obras de A. Miró son un elemento importante de la composición entera. La verbalización de las bellas artes se descubrió hace mucho tiempo. Los lienzos clásicos sobre los temas bíblicos o mitológicos tienen fuentes literarias directas. Los nombres de las obras señalan una u otra escena que resalta el artista. Cierto es que para la tradición del siglo XX son más cercanas las representaciones visuales de los refranes de Breughel. En la época del proceso de formación del modernismo S. Soloviov escribió: “En las obras literarias y de pintura más tardías es dudoso determinar donde la literatura influía a la pintura y viceversa”9. Pero antes de la aparición de las vanguardias dadaísmo, surrealismo, la influencia literaria estaba limitada por la temática o el argumento de la obra de pintura y el intríngulis del texto quedaba como una constatación de aquellas. El siglo XX convirtió los nombres de los cuadros en concepciones breves y en denominaciones o características de las imágenes (S. Dalí, R. Magritte); hizo una traducción automática de las imágenes visuales en verbales (“Los sonetos de Kimeria” de M. Voloshin). Los nombres de los cuadros de A. Miró están marcados con las mismas características de sus obras de pintura —laconismo, ironía, aire significativo— y son parte integrante de ellos. La organización figurativo-pictórica del lienzo corresponde a la estructura léxica del título. La habilidad de ironizar de A. Miró la testimonia su mini-diccionario que incorporó a las tarjetas de las reproducciones de sus obras editadas en Barcelona en 1988. Citamos “el expresionismo —expresarse fuertemente; el impresionismo— tendencia a impresionarse; el realismo socialista —producción de un pintor del PSOE dedicado a reproducir la imagen egregia del rey; el futurismo— ayerismo...” —. Vale la pena de explicar aunque solo sea algunos títulos de los cuadros de A. Miró porque, como dijimos antes, son partes consustanciales de sus obras.

En algunas obras el pintor utiliza palabras extranjeras caracterizando al personaje “The Maja today — Maja de hoy” (1975) o a la idea misma: “Gora Euskadi, Visca Picasso — Viva Euskadi, Viva Picasso” (1985); en otras utiliza títulos de libros como “Pell de brau” libro de poesías del conocido escritor catalán Salvador Espriu. A veces los títulos de los cuadros tienen un carácter más personal — por ejemplo, “Ovidi fa de Vicent a Xile” (1977): se trata del actor Ovidi Montllor, amigo del pintor, interpretando el papel de Vicente Romero cuando éste estuvo en Chile detenido durante la dictadura. Muchos títulos están llenos de una ironía escondida que tiene eco en las imágenes visuales: “Sota Spain” — “Bajo España” (1986—1987) — que es una alusión no solamente geográfica sino referida a la situación dependiente de Cataluña; “El misteri republicà” (1988) — la democracia postfranquista con la monarquía; “Temps de un poble” (1988-1989) — un tema catalán basado en los relojes tergiversados del catalán Salvador Dalí; “Quatre barres” (1981-1982) — la bandera nacional; “Intrús a Cofrents” (1989-1990) —nombre de la ciudad donde está situada la central nuclear más cercana a Alcoi; “Funcional i decorativa” (1990) —ironización de los deseos de los pintores-modernistas de hacer los objetos funcionales estéticamente decorativos de acuerdo con teorías especialmente elaboradas. A. Miró propone considerar en este sentido a la mujer; “Menina-Nina” (1980) y “La Menina de Velázquez” (1985) — inesperado matiz indecente en nombres conocidos, porque “menina” en catalán es uno de los significados eufemísticos del órgano sexual masculino.

De este modo, la palabra en su significado funcional se convierte en una clave del cuadro, “el hilo de Ariadna” en el laberinto del espejo. “El misterio de la palabra consiste en que ella es un medio de comunicación con los objetos y la arena de su encuentro íntimo y consciente con la vida interior de ellos”10. En las obras de A. Miró la palabra misma ayuda a comprender mejor la polisemántica de la vida interior de los objetos expuestos.

“Pinteu Pintura” de A. Miró tiene muchas analogías en el siglo XX. La mejor de ellas es la literaria: la nóvela de J. Joyce “Uliss” que tiene amplias lecturas. De la misma manera cada cuadro del pintor de Alcoi puede merecer muchos comentarios y necesitar un artículo aparte. Hay que decir que A. Miró tiene un libro de reproducciones donde cada obra suya está desintegrada en los elementos integrantes, lo que constituye un original aparato informativo. No obstante, como decíamos, los cuadros poseen un amplio significado, empezando por la percepción estética y terminando por descifrar cada detalle. Lo primero es, sin duda, lo más importante.

Si al destacado escritor argentino Jorge Luis Borges lo llaman “bibliotecario de la literatura mundial”, al pintor valenciano Antoni Miró es posible con todo derecho llamarlo “tesorero de la pintura mundial”. Su finca “Mas Sopalmo” cerca de Alcoi donde el pintor vive con su esposa y su hijo es como un museo; todo aquí está sistematizado y catalogado. “Mejor incluso que en muchos museos”.

Con su habitual ironía, el pintor bromeó mostrando una de sus obras de pintura-objeto (la figura del soldado-dólar que se desintegraba en dos mitades) diciendo que el que lo obtenga tendrá el benefició doble, por el mismo precio poseerá una pintura y una escultura en la misma obra.

Quiero terminar diciendo sobre Antoni Miró, imitándolo a él: este libro representa no sólo la obra de un pintor brillante sino la pintura mundial en general.

Traducción del ucraniano al español de Margarita Zherdinivska.

Corrección de Paco Bodí.

1. La cerámica tiene origen árabe, pero su desarrollo y distribución en Europa se realizó a través de Catalunya.

2. Los motivos del universalismo de los artistas en los últimos decenios, por ejemplo, en Ucrania eran de un lado la cruel censura ideológica (distintas comisiones, consejos, etc.), y de otro lado la necesidad de procurarse medios materiales de existencia. Esto explica en cierta medida la vuelta forzosa de muchos e interesantes pintores hacia el monumentalismo y el auge perceptible de ese tipo de arte. La situación, en general, no es sólo ucraniana, sino europea con cierta variación en los motivos. Está claro que la expresión sintética de la idea interna a través de las variedades de artes plásticas llevó a A. Miró, a un trabajo abnegado y al sacrificio consciente de su bienestar material durante más de dos decenios.

3. Ver D. V. Sarabianov. Estilo moderno.— Arte — Moscú. 1989. P./187 „La síntesis de las artes es un medio de eternizar las ideas y las nociones de la gente, de la sociedad humana, es el medio de eternizar la actividad vivificante de la humanidad en la unión de la creación espiritual y material“.

4. Guill Joan. Temática i poética en l’obra artística d’Antoni Miró,— Valencia, 1986. Alcoi, 1988.— P. 22.

5. Contreras Ernest. La triple muestra de A. Miró en Alcoi. Alacant, 1969, 13, XII.

6. Ver La pintura es la pintura, Vsesvit, 1989, No. 5. — Kiev.— P. 162—172.

7. Bernal Diaz del Castillo. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. Habana, 1963. pp. 71-72.

8. Romà de la Calle. Plàstica Valenciana Contemporània. Valencia, 1986.

9. Soloviov Serguey. Ensayos histórico-literarios. Acerca de la leyenda de Judas el traidor. Kharkov, 1895. P. 120.