A Valencian Artist Who Speaks the Language of Modern Sensibilities

Leonidas Donskis

Antoni Miró is a unique artist who speaks a European language of modern sensibilities. He appears as a great Catalan artist who is capable of rediscovering the mental, esthetical and cultural bridges of Europe. In fact, the political and cultural boundaries of Europe do not coincide, and they never did. The tension between political animosity and cultural enchantment or that, say, between social catastrophe and cultural flowering is always there.

This is always a rediscovery of the mysterious unity of Europe which manifests itself in the war and hate between England and Spain of the sixteenth and seventeenth century accompanied by the unfading admiration of the poets and playwrights of Elizabethan England for Spanish literature - as we know, Lope de Vega barely survived the defeat of the Spanish Armada near the shores of England, yet he was a cultural hero in England. He could have been killed in a battle, yet he was admired for his immortal plays.

The admiration of William Shakespeare for Miguel de Cervantes, especially for his Don Quixote, translated into English by Thomas Shelton, which inspired Shakespeare and John Fletcher to write the comedy Cardenio (it did not survive until our days perishing somewhere) transcended a political perception of Spain as an irreconcilable and mortal foe of England.

Wasn’t this the same that happened with nineteenth century Germany and France when the young Fichte and Hegel had much anger and bitterness about Napoleonic wars and the Jena battle in particular, yet they could raise their glasses of champagne for the French Revolution on 14 July every year admiring French culture and the spirit of the Enlightenment? Wasn’t the same happening between Russia and her former provinces or satellite states, which has always been about that same love-hate relationship or, to put it more precisely, the mixture of political Russophobia and cultural Russophilia, a stable pattern of Eastern and Central Europe?

Antoni Miró’s artistic language goes far beyond the predictable forms of the representation of the world with which we encounter each time entering the realm of modern art. At the same time, the breadth of his historical imagination is immense. I experienced this when I have had a privilege to include some of his unique artwork in the Ukrainian edition of my book Power and Imagination: Studies in Politics and Literature.

My book offered a philosophical reinterpretation of classical political and literary plots and foci, and so did Antoni Miró. Frequently described as an artist whose artistic expression, in style, ranges from figurative expressionism to pop art and realism, Miró appears as a perceptive, albeit a bit ironic, re-inventor and re-interpreter of some central themes and images of classical art and early modernity.

For instance, if I tried to come up with a challenging reinterpretation of Diego Velazquez’s masterpiece The Surrender of Breda tracing it to the conflict between the brutality and barbarity of early modern religious wars and the code of chivalry, so did Miró. This was done elegantly, in quite a daring and beautiful fashion, as if to say that nothing can be worn-out and out-of-date in our attention seeking and self-obsessed world: We still try to emulate the greatest characters and heroes of early modernity without our being conscious of this.

We are still craving for the heroes of modernity, such as Don Juan (as Zygmunt Bauman, who sees Don Juan as an early hero of modernity and also as an anticipation of the consciousness of incessant change and novelty, would have it) or Don Quixote or the Spanish general of Genovese background, Ambrosius Spinola, who disregards the key from the gate of the town of Breda in the hands of the surrendering Dutch general Justin von Nassau - as if to say that whereas the military victory is ephemeral, the long gaze and the miracle of understanding that occurs between warring individuals stays for a long time.

We try to reconcile our moral and political sensibilities with those of the past without being able to admit that ours could be far less modern than those that we tend to ascribe to the supposedly backward past. We seek our heroes in our friends or mentors, predecessors or successors, ancients or moderns. We need them. The Significant Other is what comes to us as an anticipation of our own change over time or of some neglected and forgotten aspects of our biography, personal or family story.

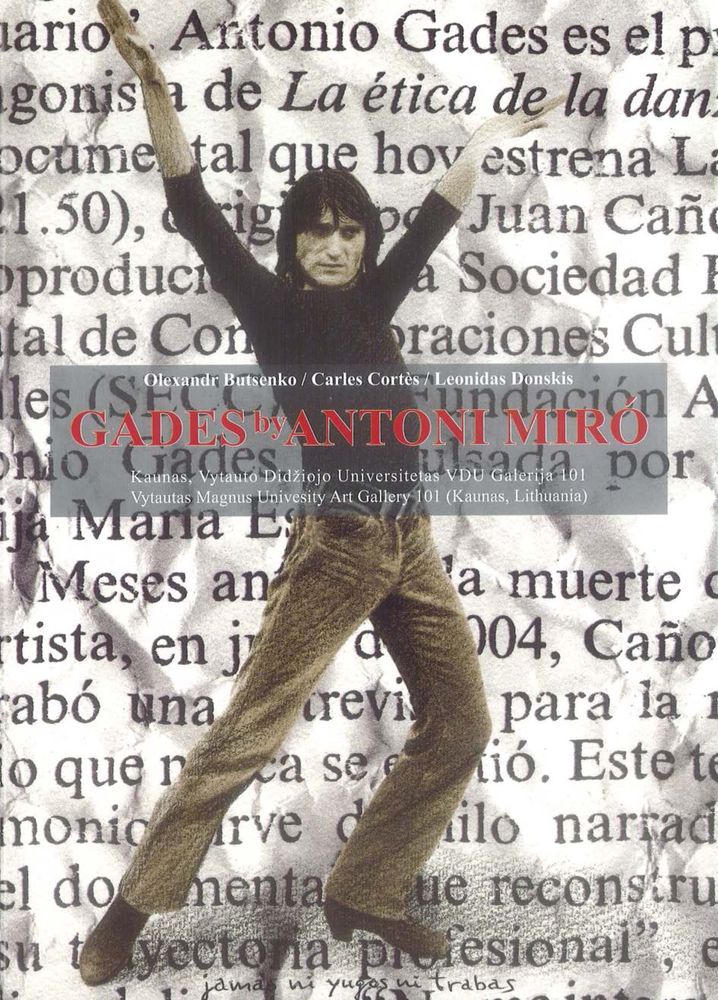

Antoni Miró’s friend Antonio Gades, a celebrated and legendary dancer, choreographer, and political activist, appears to have became his Significant Other. Therefore, the Gades project covers an immensely rich esthetical and mental territory of loyalty, fidelity and friendship conferred for a deceased friend of the artist - the friend who combined non-conformism, nay-say, political passion, and great artistic talent.

Last but not least, the project launched by Miró seems to have become a European one. It was through the effort of Miró’s and my own friend Oleksandr Butsenko, a noted Ukrainian culture personality, translator and poet, that the Gades project reached Ukraine and now landed at Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, Lithuania. The project that enables us to celebrate the art of Antoni Miró, the life and the spirit of Antonio Gades, and the modern moral and esthetical sensibilities of Europe.