The war

Emili La Parra

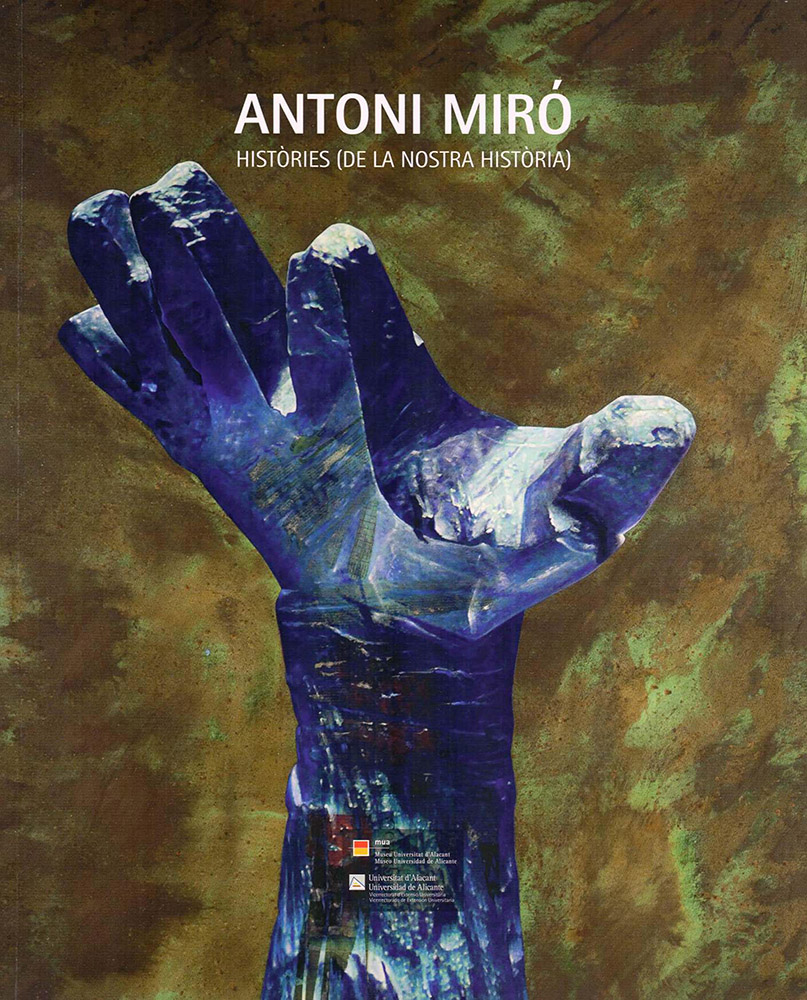

In a light essay on Toni Miró, published in 1989 by the San Telmo in San Sebastian Museoa with the title Diàlegs (dialogs), Romà de la Calle wrote: “Antoni Miró using many myths from the history, he increases in its way, its demystification to move from irony, as a catharsis to a critical action and unsurpassed parallel goal of aesthetic experience.”

The phrase, from my point of view it describes perfectl one facet of this artist, located in the line of social realism and fully committed to the problems and achievements of his time. From this commitment, his keen interest in the past arises because he knows very well that this past has shaped the current situation. Therefore, the story has a central place in the work of Toni Miró. He uses a critical -sometimes with a heavy dose of irony, sometimes with real bitterness- to play this cathartic role aforementioned by that critic. The observer of the artistic creations of Toni Miró never stays neutral, although the artist uses images generally well-known to all as they have often been reproduced in many ways. Toni reinterprets them in new contexts and shows highly suggestive, the product of his lifelong interest in experimental aesthetics.

In the exhibition in the MUA there are several works that allude to a constant phenomenon in time, which has conditioned all societies. I refer to the war. Of these works, three particularly caught my attention. They have the following titles: Vietnam, Record d’Hiroshima and Ciutat sense sortida (the latter showing the entrance to the concentration camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau from the inside views, which is unusual). All three refer to experiences that have deeply marked the second half of the twentieth century. Auschwitz, Hiroshima and Vietnam are generic names used to describe the extermination of human beings in concentration camps, indiscriminate mass death caused by the atomic bombings and the imperialist wars of our time. The three cases raise the problem of evil in contemporary culture and are also used as benchmarks of political repression, torture, fatal effects of dictatorship, oppression of the powerful over the weak... and other effects of war, as hunger and the use of children as soldiers in societies that suffer this curse on every continent, especially in Africa, a matter referred to other paintings in this exhibition.

Auschwitz, Hiroshima and Vietnam are mainly illustrative experiences of the total modern war. The term “total war” was not born in the twentieth century, but during that century, and especially since World War II, acquired a new meaning. Since then “total war” not only meant the involvement of the entire population of the belligerents in the war effort, but above all a shift in the centre of gravity of the purpose of the war: the war effort is no longer focused in the destruction of the enemy, but also in the extermination and terror detention through the civilian population. In a war like that of 1939-1945, which soon was clear the side that would win enough it had the potential population and productive capacity to maintain the complex military machine and instantly alleviate the enormous destruction caused by the new weapons it was essential to undermine the resilience of the civilian population. Therefore came to the fore the bombing of cities, without discriminating against the targets, and massive repression of the population, with other factors such as propaganda and coercive systems of various kinds. The bombing of Guernica, also present in this exhibition was, as is well known, a study in this regard. But the reality, or if you prefer, the evolution of the mechanisms used far exceeded expectations and prompted unusual results.

Auschwitz is the first reference of this new situation. His name symbolizes the genocide and the dehumanization of the population under a dictatorship, as reflected dramatically in his account Primo Levi: If This Is a Man. But it should be noticed in line with current research, that this operation cannot be reduced to a very specific group, on which is made over full responsibility for exempting it to others. The Nazi genocide was not the work of only those members of the SS, although these were its main actors and performers over bedlam. It was also attended among others the government propaganda apparatus run by Goebbels, the heads of railways for the transport of prisoners and deportees, doctors and scientists responsible for monitoring the purity of the race, officials of the Nazi Ministry of Foreign Affairs, governments and police apparatus of the satellite countries of the Third Reich and the German army itself, the Wehrmacht. The denunciation of Auschwitz, then, becomes a universal dimension.

Hiroshima recalls the horrific physical destruction of thousands of human beings, children and elderly among them. The immediate granting of the surrender of the enemy was the main reason for the Truman administration to order the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, but current studies are not limited to this argument. Show that also involved the desire to experience the destructive power of the atomic bomb (and justify the very high costs incurred in their manufacture) and the attempt to demonstrate the pre-eminence of the United States, not just to Japan but also to talk them out of action as that country began in Pearl Harbour, but also to the rest of the powerful countries.

Vietnam, in a way of continuation of the above aim, symbolizes the imperialist war in Asia and developed by a multitude of formats in several regions of Latin America. A war to ensure the American control and to prevent the triumph of revolutionary processes in the context of the Cold War; processes understood as threats to economic and geostrategic interests of the United States. But Vietnam symbolizes also the resilience of civilians by guerrilla warfare if it is convinced of the righteousness of their cause. That is, has a liberating effect, as perfectly understood the Che Guevara -also present in this exhibition in two magnificent works, when he launched the proposal to create “one, two, many Vietnams” to combat social inequality.

Auschwitz, Hiroshima and Vietnam represent the total war of our time that seamlessly spreads around the globe with varying intensity and more or less extensive areas. A kind of war starring as historian Ranzato Gabriele wrote about, often by men who are not necessarily motivated by an ideology, but fundamentally prepared to use all available means, including the ever imaginable and those that cause repulsion to those who use them, to defeat or weaken the enemy. And that enemy is a human. Toni Miró’s painting entitled Repartidor de Misèria (2006), with the image of a military jeep driven by a soldier, puts it eloquently. Material and physical poverty but also metaphysical; because the war of our time is a total war whose main consequence is the dehumanization.

In the critical and liberating line that characterizes the artistic creations of Toni Miró, maybe not useless, to end this comment, remember the poem that opens the book by Primo Levi: If This Is a Man (I turn back to this text because I think the most eloquent and heartbreaking testimony of the dehumanization caused by the war of our time):

“You who live safe

In your warm houses,

You, who find, returning in the evening,

Hot food and friendly faces:

Consider if this is a man

Who works in the mud

Who does not know peace

Who fights for a scrap of bread

Who dies because of a yes or a no.

Consider if this is a woman,

Without hair and without name

With no more strength to remember,

Her eyes empty and her womb cold

Like a frog in winter.

Meditate that this came about:

I commend these words to you.

Carve them in your hearts

At home, in the street,

Going to bed, rising;

Repeat them to your children,

Or may your house fall apart,

May illness impede you,

May your children turn their faces from you.”