75th Anniversary of the Swedish-Norwegian Hospital in Alcoi, by Antoni Miró

David Rico

In the seventy-fifth anniversary of the war hospital established in Alcoi, known as “Hospital Sueco-Noruec” –Swedish-Norwegian Hospital–, there are still some people, both in and out of the city, who want to pay the most heartfelt and deserved tribute to it, not only for the social and human importance it had, but to a great extent also for the vital function it performed for many individuals in its time, in spite of its brief existence.

Despite the time past, it is still in our memory: the invaluable humanitarian aid given by the thousands and thousands of Scandinavian citizens who, in that year, 1936, decided to move to more than three thousand kilometres away to the other side of the continent to gather enormous quantities of materials and different resources so necessary in critical moments. Thanks to the solidarity of these people, and of so many others along the entire conflict, many lives could be saved and the survivors could continue forward, being able to bear witness to his experiences and memories.

There have always been old and well-known stories of solidarity and today we will tell that story again: Antoni Miró wants to give testimony of a distant reality, and he does it starting with a set of time images he reinterprets with his particular vision, where some of its protagonists appear, be they well-known or anonymous (it doesn’t matter!), to refresh our memory and learn again, once again, from our past. Black and white images, or rather, in different gradations of gray. However, the world has never been like that. Gray, loaded with expressiveness and significance in so many images, is responsible for transmitting a strong feeling of distance, of sadness, of doubt or even of a shaded melancholy, even more so if the images we observe transport us to distressing moments, of extreme famine, full of misery, poverty, suffering and death such as in a confrontation between neighbours, friends or brothers: war. The infinity of grays shaping certain images of the past, snapshots captured by a brief moment and shown by simple human election, are a contra natura way of observing reality.

Lately society has been flooded with a list of unlimited images of armed confrontations reported “in colour” between neighbouring villages, whose names we can’t probably remember. This use of colour has provided us with a clear, immediate link to the reality surrounding us, bringing the images and the observer closer together through the reality of colour, somehow, transmitting a natural sense of contemporaneity. Human eye, as main tool of this analysis of reality, has always been able to capture light, and therefore, to see colours in very diverse ways, using brain without apparent effort.

To look at life in colour and not only in black and white, in a wide scale of grays. Maybe this is what Antoni Miró proposes us with his interpretive and critical personal view of the facts: to add a chromatic touch to the snapshots of our forefathers, of people like us who reacted to defend their ideals, in the most consistent and sincere way they knew. To add colour as someone adding a vital spark to moments captured once from a set of photographs, incomplete to some extent, in order to transform this color into a bridge between the anonymous protagonists of the past and the individuals within today’s society. Colour as a demiurgic force, creating a link to the present time, necessary not to forget the witnesses of a dramatic tragedy such as the Spanish Civil war - by extension all wars -, as uncivil as those who propose and declare them, hiding away in their safe shelters, deserving the hugest social disgrace. This tragedy getting more dramatic, if that’s possible, because of the defeated fighters becoming victims of repression and public humiliation, condemned to be forgotten and silenced, humiliated and to the ius puniendi of the winners.

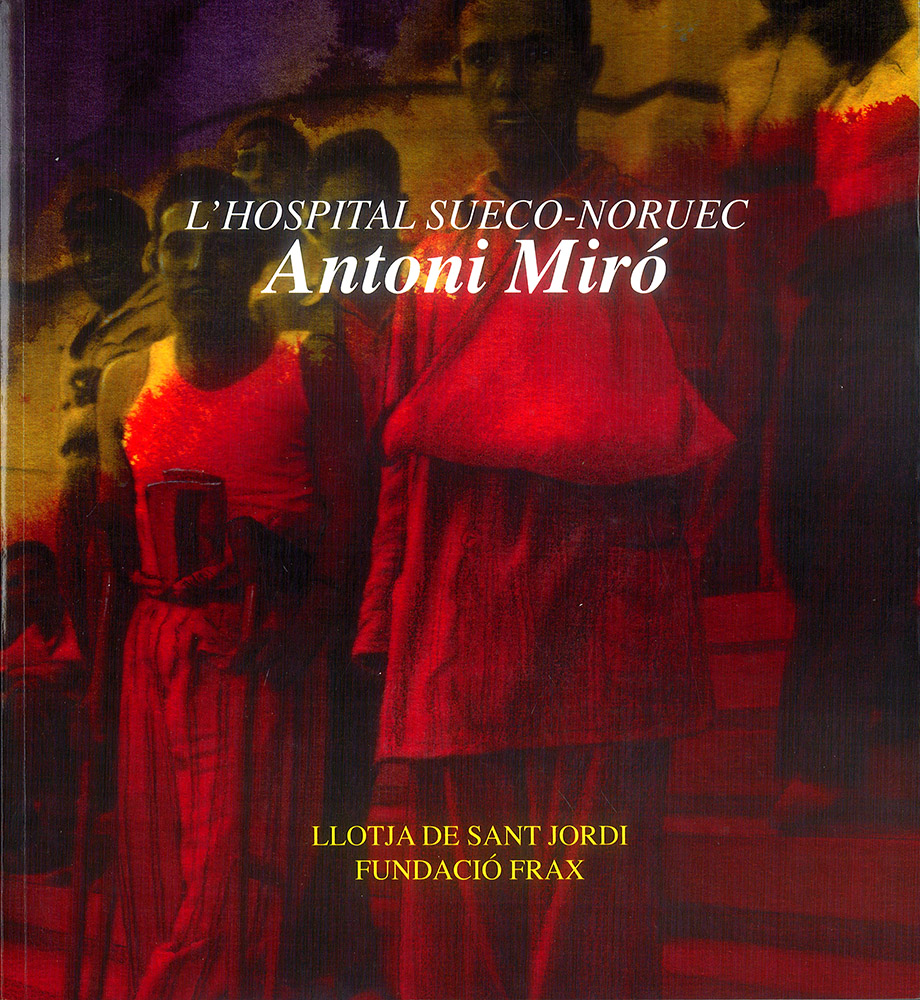

That’s why the different grays of the images, simultaneously monotonous and dull, now come alive thanks to Antoni Miró’s skilful paintbrush, with wide spaces of color or subtle contour lines, studied strokes highlighting certain characters, objects and sceneries, to break the heavy dark gray. An impressive effect emphasizing the shapes, the objects, the faces and the expressions, exalting them. A combination of yellows, reds, blues and greens, oranges and purples dancing together with the shaded gray of the original images. He uses especially red as he does in most of his long artistic journey, because it is the color of the blood spilt in the struggle, and both his life and his profession are inseparably focused on the bloody struggle for recognition and defense of what he thinks it is right. Bloody because red is almost always present, profusely, to raise his voice, to point, to attract attention and interest, to get our attention and to denounce, aloud but without words. This is the case in the portraits of the politician Georg Branting or the doctor Manuel Bastos Ansart, of the trade unionist Vahó Nicomedes or the poet Joan Valis. So different, and yet so similar. So distant and yet so close at the same time, thanks to a few common ideas, almost universal for them. But also in the ambulances, the blankets of the injured men or the shirts, coats and caps of the photographed characters, colouring the operating theatres space or dyeing the sky in an outdoor scene. A colour, red, reigning over the rest, generally due to its expressive power, but also chosen by its symbolic force.

In this set of paintings it stands out how the artist from Alcoi uses the emblematic colours of the Spanish Republic, red, yellow and purple, in an original and remarkable way in many of the scenes recalling different facts in Sweden, Norway or Spain. The colours of an ideology related to democracy, to equality among people, to their total freedom. Three basic colours trembling softly over the wounded and disabled veterans at the stairs of the “Sueco-Noruego”, on the front line, in the middle of an operating theatre or recovering while they are reading or writing to a loved one. Colours separating people in one of the meetings to collect funds inside a theater, or ranking the space where troops and republican volunteers march past in the main square of the city of Alcoi. But he does not only use this resource here. Miró also uses the three-colored combination to highlight the mood of individuals such as the mayor Evaristo Botella, sitting at his desk, and later imprisoned in the “Sueco-Noruego” and later shot (as well as many others were also imprisoned in its cellars), or with the still recovering wounded soldiers in the war hospital, even in scenes where thousands of people demonstrate through many comers of different places, onto the streets to defence a legitimate republican government, the Spanish one, in a sublime act of solidarity and brotherhood.

Accustomed as we are to think, imagine, even remember people caught in an ancient and distant world of gray images, perhaps even too unknown a world to know its protagonists, we are not often capable of valuing the temporary actors of a whole set of small heroic actions. Antoni Miró wants to highlight, once again, some of these values and actions to the whole world, through some of these people, from the experience of the “Sueco-Noruego” Hospital, in order to get them out of anonymity and forgetfulness, to pay a fitting tribute to a part of society who, voluntarily, took part in a magnum movement of social action to defend civil rights and justice in a distant country, even turning into protagonists of this story, of the History one day others would write. A rara avis nowadays we should take note of very carefully.