Shared, eternal Art. Intertextualities and common spaces

Carles Cortés

“He uses paintbrushes, she uses words. Antoni Miró and Isabel-Clara Simó have been friends for many years [...] Both belong to what is known as the 1960-70 generation, were born in the same place, Alcoi; both have believed and participated in many shared adventures for a fatherland-motherland that is more of a dream than a possibility, have fought for a better world from their own art and their own conscience” Josep Piera

Midnight at Sopalmo, a country house and workshop near Alcoi, in the Valencian Country. Antoni Miró, one of our protagonists, paints his dear friend in the silence of his room. Songs by Feliu Ventura, a bosom friend and singer-songwriter from Xàtiva, are heard in the background. At the same time, the words form intense and sincere verse lines that unlock the gates of your heart to open them wide, in the darkness of the soul. These words are by Isabel-Clara Simó, the other protagonist. Painter and writer share languages, exchange impressions with their different tools in coincidental expressive spaces. Ties that prove the well-known Horatian maxim “ut pictura poesis”, demonstrated through the ages by theorists and experts in comparative literature and discourse interaction, such as Daniel Bergez, Joseph Joubert or Garcia Berrio, among others.

The writer states that “this is a man who works tirelessly, never lowering the bar. I am talking about a genius, called Antoni Miró.” Meanwhile, the painter praises his friend in verse lines without a canvas. Antoni Miró is not a poet, or is he? And yet he is a self-taught artist who has drawn inspiration from the leading writers in Catalan literature, like Miquel Martí i Pol, Salvador Espriu or Vicent Andrés Estellés. And he proves it: “what winds clear your secret places of wisdom that we find in the dark.” The two friends were subject to creative censorship in the ominous post-war period. Their lives mirror their work. The anti-Francoist fight for the freedom of peoples, for the survival of art and literature in a forbidden language whose speakers were persecuted during the 1960s and 1970s, still nowadays regarded by some as a second-rate language. An analogy of both languages that has been studied by M. Carmen África Vidal Claramonte, who exemplifies how this kind of comparative analysis can be conducted through specific cases of writers and artists throughout the first three decades of the 20th century, in Paris; for instance, the interaction between William Gaddis and Julian Schnabel, on the one hand, and between Kathy Acker and Sherrie Levine, on the other; at the same time, the work of René Magritte, Ruscha Cobo and James Lee Byars is also examined.

Our protagonists’ ideological and personal coincidences become crucial when it comes to understanding the conceptual parallelisms between their respective bodies of work. A line of analysis based on the analogy of contexts, the comparison between artistic products in the hopes of comprehending the extra-literary background shared by the two artists who are compared.

Already in Barcelona, Isabel-Clara Simó started her career as a writer. From then on she never stopped writing, obsessively. Tales, novels and, in her final years, poems – we have inherited her body of work, an immense and multifaceted canvas of characters and forms, true to her motto: “Literature is an art form, not a pamphlet or a weapon.” Simó was never deemed a poet until her final, subtly activist period: “You have been called stupid and vulgar. And they have done so with the most terrible weapons: those that make you feel dizzy, given all the love you pour in them.” Before writing these verse lines, included in her book of poems La mancança, she had already published her first poetic work: El conjur, 2009. Despite the distance between Barcelona and Alcoi, Miró and Simó always kept in contact: both friends exchanged confidences, added nuance to aspects of their joint work, or even their emotions towards their other common friend: singer-songwriter Ovidi Montllor, from Alcoi, who was recently paid tribute to in his hometown for his 25 years of holidays:

Dear Toni, At last, here are my poems. If I didn’t love you so much, I wouldn’t have made the effort of sacrificing most of the graphic elements (you don’t deserve me, man!) because of your doubts, which you know I greatly respect. Now it’s almost ready, other than 4 or 5 trifles. I hope you will include in the text. Even the “O” I liked so much has been simplified for you. There, you win. How typical of someone from Alcoi, you stubborn man! Barcelona, 2 November 1994.

Isabel-Clara Simó

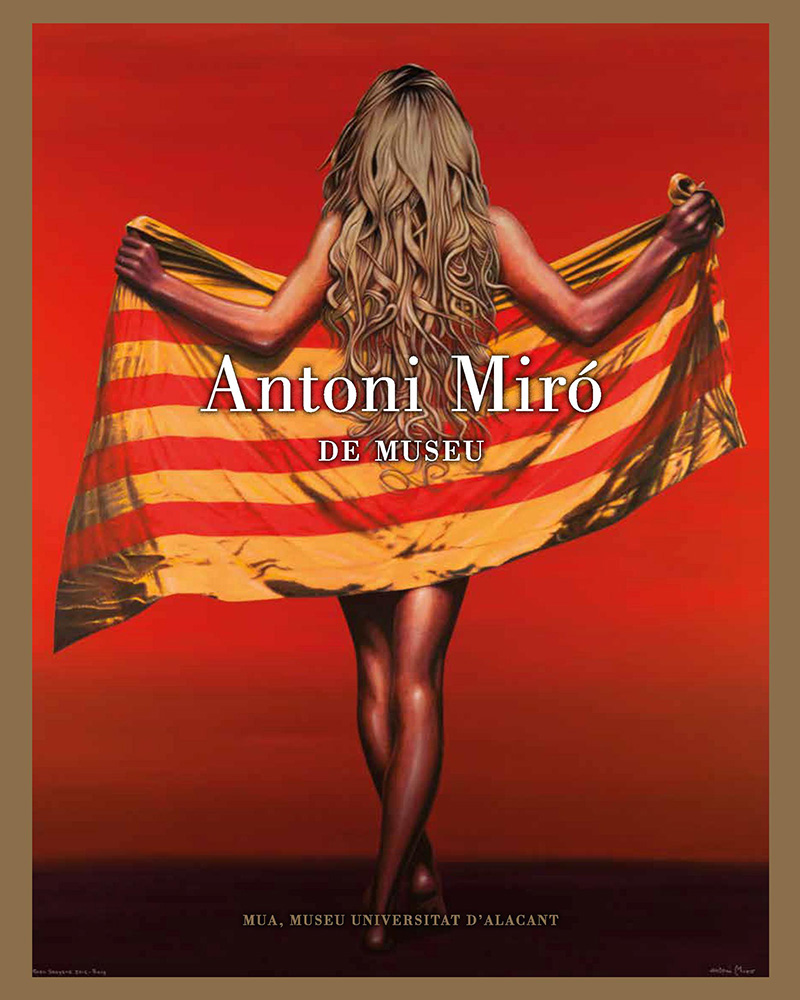

The poems the writer refers to are part of an exhibition, ABCDARI AZ, made up of 24 tables of letters of the alphabet painted by Miró in 1993 and an introductory poem, written by Simó, for each piece. A set of pictorial works of high visual regularity, where blue and violet hues dominate and the letters of the alphabet stand out, alternating the dominant colours in each piece. Each table refers to a letter, except the twenty-first, which contains three letters (U-V-W), something the artist did to ensure the regularity of the resulting mural. As for the poems, all in free verse, it should be noted how Simó uses characters from classical Graeco-Roman literature and biblical tradition, completely unrelated to Miró’s drawings. An iconic joint work that never ceases to surprise the viewer. Also surprising was Miró’s “Suite eròtica” (1994), twenty etchings that paid tribute to the eroticism of the classical Graeco-Roman world. They were accompanied by “Sexe bell”, a poem by Isabel-Clara Simó: “Can’t you see it, that there is life in the beating members that look for the humid crevices that are the source of everything, the origin?” The eroticism of the Graeco-Roman world, a new space for creation shared between both friends, as we had anticipated in our study ABCDARI AZ (1995): poesia i pintura d’Isabel-Clara Simó i Antoni Miró, which came out in 2007. But Isabel’s first poem was dedicated to her friend Toni in 1987, entitled “Per Antoni Miró, el millor pintor del món” and first published in the book Trenta al Cercle vers Antoni Miró, a compilation of poetic accounts intended as a tribute to the painter. Afterwards, in 1999, it was also included in the monograph Prohibit prohibir.

In addition to Isabel-Clara Simó’s poems we should mention all the texts and prologues she wrote for many catalogues, in which she focused on Miró’s work: El Dòlar. Antoni Miró, with a prologue by Isabel; Suite eròtica (a Grècia fa 2500 anys). Món d’Antoni Miró, written by Isabel Clara Simó and containing photographs by Faust Olcina. The prologue to the first biography, written by Gonçal Castelló; 20 aiguaforts d’Antoni Miró; Antoni Miró. Els ulls del pintor; L’Ovidipopular. 21 anys de vacances; Mireu l’Ovidi: el Convent, espai d’art; Prohibit prohibir: Antoni Miró. Antològica 1960-1999; Antoni Miró: “Vivace”; La Volta d’Antoni Miró; Les bicicletes d’Antoni Miró; Viatge interior; Volem l’impossible Antoni Miró: antològica 1960-2001 or El tribunal de les Aigües, among other texts and contributions by Isabel-Clara Simó (“Els ulls del pintor”; “Les impostures”; “Silencis i crits”; “Ser pintura” or “Mira Miró”).

Over the last few years, Miró has painted Isabel-Clara Simó at different times in her life. Since 2012, a portrait of the writer has appeared in several catalogues; for example, the one on the “Personatges” series, still to be completed with new images of illustrious figures of the cultural scene. The same portrait is seen in the “De mar a mar. Antoni Miró” series, with an introductory text by Josep Sou that once again highlights the interplay between author and artist: “A sign of identity. A strong friendship built over years of happy concurrence. Many projects of written lines or of canvasses soaked in the substance of unyielding affection.” The next year, the artist painted Isabel’s youthful countenance during the dark times of Francoism; surprisingly, her gaze is steady and joyful. The same work was added to the catalogue Personatges. Antoni Miró, at Xàtiva’s Sant Domènech Culture Hall and to the catalogue of the same name at Castelló’s Menador Culture Hall. There is an acrylic painting that shows her at Sopalmo in 1984, titled “Sóc Isabel”. Throughout his career, Miró has also made sculptures, like his well-known works in COR-TEN steel: “Estimada Isabel” (March 2013, 187 x 240 x 40 cm) and another piece (size: 202 x 250 x 40 cm) located at Sopalmo. Moreover, the artist produces at least fifty small sculptures that can be found all over the country.

Despite Isabel-Clara Simó’s recent passing, the relationship between both friends goes on. In fact, the sculpture “Estimada Isabel” stands beside her ashes at the cenotaph of the Alcoi cemetery, right next to her dear Ovidi. Not only that: he will certainly surprise us by dancing new tangos of brushstrokes with the author.

Finally, as is evident from the combination of various languages, techniques and resources, artist and writer deploy an inversed communication strategy that makes reference to the syntax, semantics and pragmatics of the work, with a mixture of language devices. All in all, we have observed how their joint work provides further proof of the interplay between novel visual languages and literature. Similarities that have been pointed out by critics throughout history, for example Daniel Bergez in the closing words of his essay Littérature et peinture: “Décrire n’est d’ailleurs qu’un intensif du verbe écrire: le partage d’un même lexique entre littérature et figuration semble renvoyer à une même fonction essentielle.”