Antoni Miró and the Valencia Water Tribunal: Historical perspective and artistic passion

Armand Alberola

Antoni Miró, the painter from Alcoi, has devoted one of his most recent series of paintings to the Water Tribunal of the Plain of Valencia, one of the most remarkable institutions in Valencia and known to Valencians simply as the Water Tribunal. This may have been at the instigation of some person or persons, but knowing the artist who lives and works in Mas Sopalmo, and knowing his interest and concern for the history and affairs of Valencia, I have no doubt that sooner or later he would have taken up his brush to transmit, in his own inimitable way, the most important facets of this distinctive tribunal, which for centuries has settled the disputes over the distribution of the water from the river Turia which irrigates the Valencian Huerta.

Water and land have always been closely connected in the ancient territory of Valencia. And since there is not always sufficient water to satisfy the thirst of the fields, it has been considered by farmers as the essential element, more valuable than even the land itself, as it is water that has enabled agriculture to yield up its fruits and enable a society, acutely aware of the limitations imposed by the physical environment and the climate, to sustain itself, grow and progress – a society that has spared no effort and has invested heavily to confront these challenges. Numerous examples of this are conserved within our historical memory.

In the apt words of the song by Raimon, an inhabitant of Xàtiva, “the rain doesn’t know how to rain” in Valencia; when it rains little it’s a drought, and if it rains heavily and violently it’s a catastrophe. And so our agrarian and irrigation systems have evolved to respond to the lack and the excess of rain, two sides of the same coin. While the northern and central parts of the Valencian territory benefit from long rivers carrying an abundance of water enabling irrigation wherever they flow, in the southern, almost arid parts, it is much more difficult to sustain agriculture based on irrigation, and if fact the territory is best described as irrigated “drylands”. Varying volumes of water have led to the creation of effective irrigation systems which are responsible for bringing water to the furthermost corners of the fields and gardens of the Huerta. These systems, most probably originating in Roman times, underwent major expansion and improvement during the centuries of Arab rule. Following the Christian reconquest, the system of water distribution went unchanged, as was documented in regional laws (fueros) and in municipal charters. Later, during the late Middle Ages and the early modern era there were important innovations and the network of irrigation channels was extended and dams and reservoirs built while local laws were introduced which brought an end to the oral tradition, which had always been respected and applied hitherto. A unique water culture gradually emerged being closely linked to another culture we could call the culture of hydrological survival and which, from the 19th century onwards, attracted the attention of engineers, technicians and experts from France and Britain looking for inspiration and solutions to the problem of irrigating semi-desert areas in their colonies.

Every Valencian system of irrigation in history has had its distribution networks, with mechanisms to control the water and with bye-laws and tribunals responsible for ensuring they work well. The most well-known of these is the Water Tribunal, which is included in the unesco list of World Intangible Cultural Heritage and is reputed to be the oldest working judicial institution in Europe, claimed by experts to be “unique in the world”. King James I, after the conquest of Valencia and by means of various local laws granted full legal status to a body which till then had been exercising the function of water tribunal. The passage of time has shaped the character and content of a venerable institution which is widely-respected to this day. It continues to meet at the Apostle’s Door of Valencia Cathedral before the bells on the Micalet tower strike 12:00 every Thursday, except on public holidays and the days between Christmas and the New Year.

The Tribunal is composed of eight judges, or trustees (síndics), elected democratically by the communities of irrigators from each of the channels, whose dams funnel off the water of the Turia river and guide it to the fields. There are three communities on the left bank – Tormos, Rascanya and Mestalla – and five on the right bank – Quart, Benàger-Faitanar, Mislata, Favara and Rovella. The Tribunal is separated from the public by temporary railings and each member sits on a seat inscribed with the name of the irrigation channel he represents. The sheriff (alguatzil) calls the accused by the name of the irrigation channel they belong to. The session, held in Valencian before numerous onlookers who follow respectfully, proceeds rapidly and with exemplary behaviour by all those involved. The ruling is issued, orally with immediate effect, and is then recorded by the secretary. There is no appeal. These proceedings, according to Víctor Fairén, adhere to the principle of pure orality, as they are perfectly clear and concentrate in one single ceremony all the court proceedings.

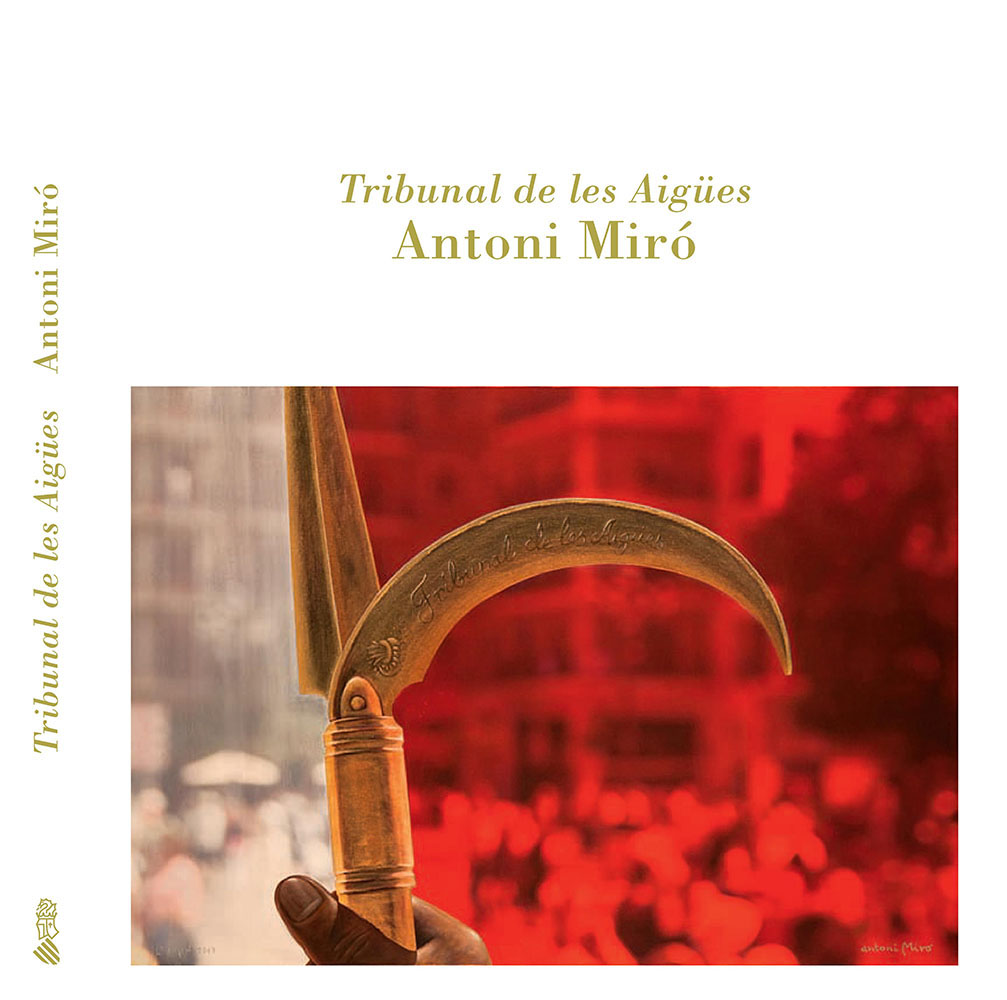

Antoni Miró, with his inquisitive gaze and precise and limpid brush, has returned to a field he has already explored and knows well, and to which he has dedicated more than one of his series: the field of history. On this occasion it is to take up the tremendous challenge of interpreting the ancestral memory of his own land. And what he demonstrates is that the Tribunal is nothing without the water, without the irrigation channels, without the regulators and dams, without irrigation, without the landscape of the Valencian Huerta. All these elements impregnate his canvases and force the viewer to contemplate the water running through the channels of Mislata, of Mestalla and of Quart-Benàger, to imagine how it expands and floods the Huerta, to recognize the details of the hydraulic infrastructure which mark out these veritable water trails; trails on which one can pilfer, “misappropriate”, the precious liquid needed for the crops, and which, if it fails to reach its destination in the agreed volume, can harm the interests of the irrigators waiting their turn. These are issues the Tribunal has tackled and which it continues to tackle to this day.

Antoni Miró summons up the full force of his painting, all the ability his art can muster to attract the viewers’ attention, and his unique gift of transforming a historical reality into art which can move us to ponder; all this he takes and applies it to painting the place the tribunal holds court in Valencia Cathedral’s Apostle’s Door, the paraphernalia associated with its simple components – eight seats and some metal railings –, the moments just before the tribunal is constituted, and the liturgy with which the main figures enter the dramatic scene in order to commence the centuries-old ritual. In his canvases we find all the elements of the entire historical and legal framework which has made it possible for the Tribunal to survive: the Apostle’s Door, the vestidor (robing room) where the members of the court await the beginning of the ceremony, the cercat or corralet (enclosure) where the eight seats to be occupied by the trustees are carried, the solemn procession which leads the members to the Sala del Tribunal (Court room), where, in the presence of the sheriff and before an expectant public – despite their evident numbers, Miró skilfully blurs the public out in order not to upstage the institution itself – they initiate, as on every Thursday, the ritual of ruling on the conflicts that have been posed through history and continue to be posed by the distribution of water in the Valencian plain. And Antoni Miró, as he has done before with other landmarks of our common history, leaves a typically passionate record of great artistic beauty.