Antoni Miró: Art and solidary commitment

Armand Alberola

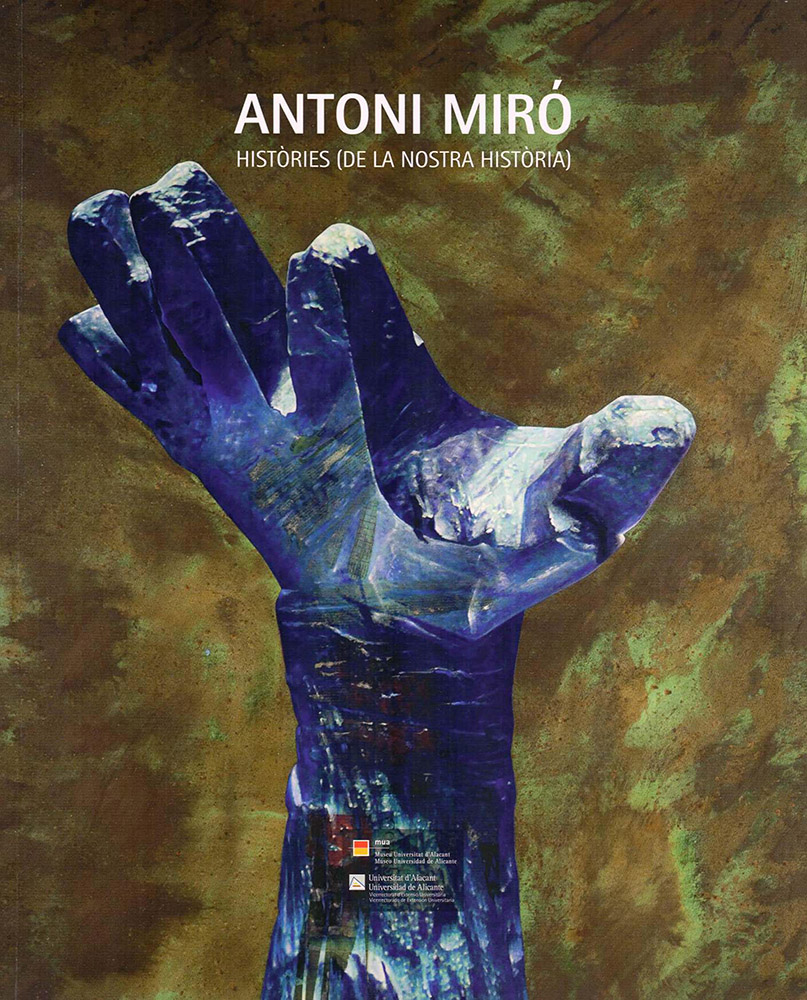

The first thing I have to say is that these lines are not written, they do not pretend to be, from the perspective of the artistic critic, among other reasons, because I don’t consider that I am sufficiently qualified for it. However, the gaze of the whole work of Antoni Miró- that “solitari far que aguaita nit, molt a migjorn del nostre país rar” [Lonely lighthouse awaiting the night, everything at midday of our rare country], defined by Salvador Espriu suggests so many things that we cannot remain impassive. The anthological exhibition that the Museum of the University of Alicante dedicates to the artist from Alcoy, serves as an excellent excuse for allowing me to highlight what, from my point of view, is a paradigmatic example, inextricably linked to socio-political reality of a country and its people in a moment of history where it was not easy to take certain decisions, and it shows very specific and risky attitudes without ambiguousness.

Antoni Miró is the kind of man who, throughout his life, has managed to combine his undoubted value as a painter, engraver and sculptor with strong evidence of commitment. At this point I will not discover what that –“home que pinta” [Painting man]- Miró has represented and still represents to the culture in the broadest sense of the term, the land of Valencia and, by extension, the rest of the Spanish state and the world in general. Few years ago, when Antoni (Toni) Miró turned sixty wrote how much I admired -and why not say: I envied- those who, like the artist who lives and works at the Mas Sopalmo are able to transfer to the canvas, to the table, the board, to any surface, images, colours and feelings ready to move to the joyful contemplation of beauty, to move us to the message they contain, to make us share a deep reflection or get involved in advocating the bloodless rebellion. The sight of many of the works of Miró has led me to these destinations.

The fact that the University’s Museum (there are not many in the country as the Museum of the University of Alicante) is hosting an anthological exhibition of a nonconformist committed and recognized artist, as Antoni Miró is a good evidence that, fortunately, there are certain things willing to change. However, others won’t, in the complex and sometimes inextricable academia environment where more than the necessary and advisable times, “worship” adopts incomprehensible garments, and costumes that seem unnecessary for the initiation rituals for the non- followers. And yet there are people in other areas, civil society, “the street” –are able to -transmit values, lessons, education, and culture through their art. It is worth for the university to gain and grant them a spot and prominence for their work, so they can see analyse absorb, and recognize the values and root in its essence. That is, from my point of view, what happens with Antoni Miró. Because that young man, in the mid-sixties of last century, scored decisively in his diary that “volia ser pintor” [he wanted to be a painter], he is today a dedicated man who reached long time ago that goal he set in his distant adolescence. Not without effort, as evidenced by the hours and miles travelled by Miró and the various twists that art offers to those who, like him, are endowed with this special gift and magic allowing them to be owners of this ability to create beauty and transmit emotions and feelings.

It is somewhat rhetorical to adduce that, after such a long history, the visual language of Antoni Miró has evolved. In my opinion, there are certain aspects that, as identifying keys, have remained untouched in his work, allowing and making it recognizable: his mediterranean spirit, the defense of cultural and national opinion and the heavy burden of social criticism, complaints and defiance. I still see traces of alive realism, social activist born in belligerence years against the Grup Alcoiart or the Group Denunzia in the works, and not only the oldest - as outlined in the Anthology of MUA, its opposition to totalitarianism, oppression, intolerance, racism, the manipulation, violation of human rights, war...

Time has not made him retreat of his principles and commitment. On the other side, it has allowed to decant his expressive language and communication skills. His external appearance has hardly changed. He maintains that professorial air that struck me when I met him: the simple, discreet, softspoken and calm in the expression, without fanfare but firm in his convictions. I can easily imagine him, with his long white hair highlighting over his impenitently black clothes, teaching a history class at the university. Although he does not like public speaking, reeling off the significance of its series “Amèrica Negra”,”L’Home avui”,”El dòlar” in its various interpretations (American imperialism, the Chilean tragedy after the Pinochet coup closest history as a country),”Pinteu Pintura”,”Vivace” or more recent “Viatge” to the Greek roots of its Mediterranean spirit in which, moreover, he fully identifies himself occasionally on canvas and makes a nod to a past or present through the art or the forged metal pieces that exhumed reality in order for the solar craters to wrap and immortalize the rain or wind.

I must confess that I have always liked especially the series “Pinteu Pintura”. Perhaps because I am a historian. And I’ve come to believe that, using some of his paintings or sculptures, could visually enrich my classes and offer my students an unusual vision of the Count-Duke of Olivares, King Charles III “The Hunter”, above all, and reformist - “malgré lui” - Velázquez and his meninas, the surrender of Breda in the form of “llances imperials”, the recreation of Goya and his work ... But now and the story of a country also paraded before our eyes, thanks to the work, methodical and meticulous of the artist from Sopalmo. And this retrospective exhibition includes a gallery of characters who have shaped the sociocultural becoming of this land (Pau Casals, Joan Coromines, Ovidi Montllor or Joan Fuster), the perennial resistance –see his captaires inequality—his unique tribute to Picasso, Bacon and Leonardo da Vinci, his cry against the suffering of people regardless of their nationality and religion, its rejection to the war or vision-always critical and foreboding of some realities: if there is any doubt, he includes there his complaint about bullfighting and the facts and situations that have marked us the most.

This year, I wrote the introduction of my latest book that the university as an institution developing and transmitting universal knowledge, was indebted with those that came from areas outside of it, and the ones that had helped to build a space where people of the street could acquire these essential tools and help us free them to make up the culture and education. In that text I was referring to Raimon, the poet and singer of Xàtiva who helped to make the work of classical authors in catalan, reach all corners of a complex country and, at times, perplexed. Within a year, Raimon receive recognition from the University of Alicante, which granted a Doctorate “Honoris Causa” for his decisive contributions made from the “outside” but with an efficiency and dignity worthy of the praise. The times were not easy. Antoni Miró, a good friend and all cultural references that have contributed to the construction and maintenance of the identity of these lands, has also gone a similar route carrying their flag and contributing to art, with his proverbial generosity to any cultural project ran out of not caring help the place or the circumstances in which it was required. Miró painted, engraved or carved our history, the more remote and the most current and he left his stamp on those institutions that were lucky enough to count on his cooperation. Everything from his deep convictions, from the purest social and political activism, fighting with the finest weapons that humans can use, with method and patient, and without ever giving up his plastic voice. The other, he tries to keep it on a minor level, reached every corner of the sensitivity of others, arousing feelings hidden and contributing to that. Sometimes, the country regained identity and was slowly waking up. It goes without saying that the Miró’s work seems, to this day, as necessary as before. I have no doubt that he himself is aware of this, and that he will continue his efforts in the form of art giving us their full commitment. As he always has.

This anthology can only collect a selection of his broad and generous artist from Mas Sopalmo and makes him a member of this university community that pays homage and confirmed that, obviously, is an evidence: sooner or later, recognition comes to whoever deserves it. And without any doubt this is the case of Antoni Miró.