The history of a time and a country

Josep Forcadell

Molt a migjorn del nostre país rar, aguaita nit un solitari far.

Salvador Espriu: “Món d’Antoni Miró”

To a friend…

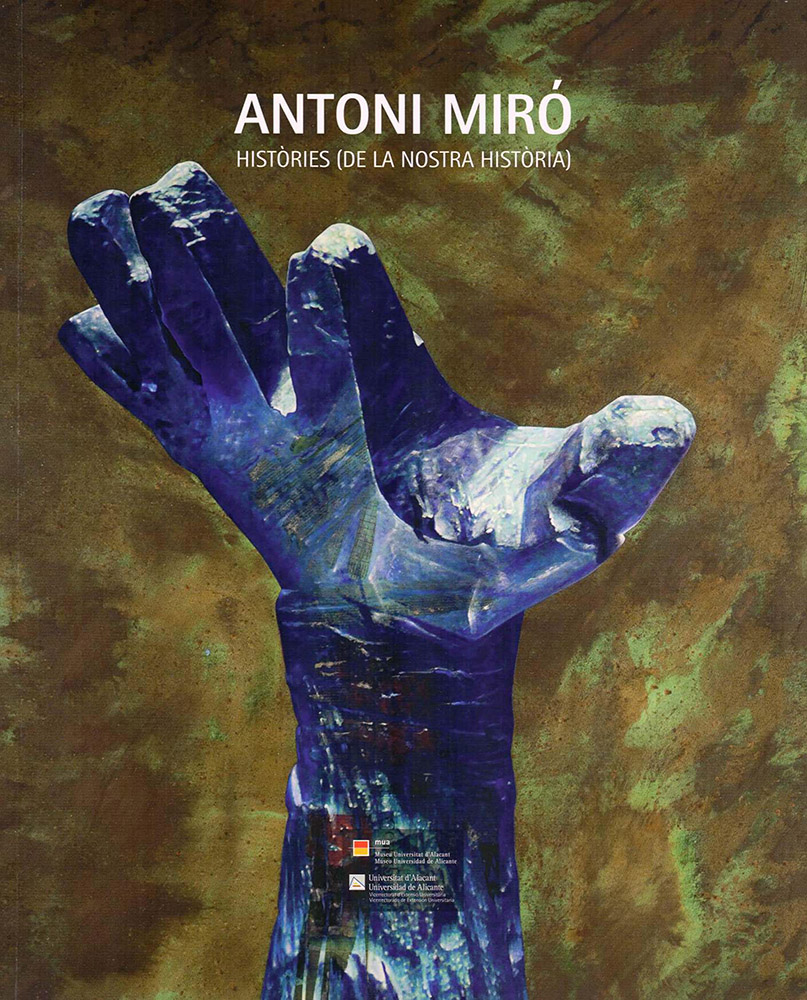

Antoni Miró i Bravo (Alcoi, 1944) is a methodical and tireless worker, an observer and a painter committed and demanding, who, by the desire to continue the family occupation, has also worked with iron and bronze. It is impressive to see the diversity of techniques and media, or the breadth of themes and looks of this creator. His work has been studied and presented by experts, some of them friends; it is true, but always critical and rigorous as Romà de la Calle, Manuel Vicent, Wences Rambla, Joan Àngel Blasco, Isabel-Clara Simó and Ernest Contreras. More concisely, but with equal enthusiasm, Antoni Miró has been recognized by artists, poets like Salvador Espriu, Joan Valls, Rafael Alberti, Josep Corredor-Matheos, Vicent Berenguer, Francesc Bernàcer, Marc Granell, Josep Piera, Jaume Pérez Montaner, Josep Pérez i Tomàs, Eusebio Sempere, Pablo Serrano, Ovidi Montllor, Antonio Gades...

However, I don’t have the basics to explore the work of Miró as some art critic would, or inspiration to gloss, as they, the poets, do. If I have the honour to participate in this catalogue, if I give my point of view on some of the work presented herein, it is due to my poor knowledge of history, my great admiration for Antoni Miró´s paintings and my commitment to this land where the world, as would say Bernardo Atxaga, is called País Valencià -a shared and discussed commitment with this man from Alcoi-, and specially for the sincere friendship which binds me to Toni. You know what the saying goes, for a friend... I will do whatever he needs!

The good literature

I like history, the history of all cultures and peoples. So, I enjoy reading the historians who, such as good novelists, build speeches to help us understand the complex reality or a small piece of it. From the biblical Genesis, the Homer´s Odyssey or the Chronicles of King James I, good storytellers tell stories, paint realities, creating worlds. The power to devise a new reality if there is nothing radically new in art- is what attracts from creators. Some people compare the art with the creation of the world and the artist with a kind of god or goddess. Isabel-Clara Simó goes further and claims that Antoni Miró is god and a woman, in the sense of creation and productivity. Let me then focus on the paintings that Miró Antoni, with the fertile seed of other stories, brings us a new vision of history itself, to enrich our points of view with amazing versions of reality, restless creatures, and often disturbing, always growing.

Over a decade and with a good dose of provocation, irony and caustic, Antoni Miró gave us alternative visions of masterpieces of painting. Like that poetry-tool vindicated Celaya, away from the neutrality of the damned who see only escape in the culture, the work of Toni is a loaded gun in the future. The painter from Alcoi was committed to work to all men and peoples drowned by the Franco dictatorship, by U.S. imperialism, poverty and exclusion from this so called “welfare society”. Vietnam, Chile, Cuba, United States, Gaza, Baghdad, Auschwitz, our country ... there is nothing alien to a committed and honest painter. An anecdote, a detail of a character or a story, the fly on the head of La Gioconda or the ace of clubs on the hat of the Count-Duke of Olivares are the bait Miró uses to hooks us. The emotional and intelligent answer of the viewer is almost unavoidable, so now we will have to finish the story, to rethink the purpose and, as the author did, pass the intention of the first image through the sieve of criticism. What causes, if not, people or Manhattan people? or Sedutta ed abbandonata? Many questions and the need to explain or recreate what the author intentionally tells us partway. Everyone makes their own reading because the more you watch it, the more suggestive and open is the work of Miró, who lends part of the responsibility of the story told to the viewer of his paintings. That’s why we say “Pinteu Pintura” (paint paintings) instead of “mireu la meua pintura” (observe paintings).

Pinteu Pintura

Since the 80s, I began to look more closely at the work of Antoni Miró. It helped me to come to live in Alicante and a visit to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Elx with Sixto Marco. I was struck by the paintings of the period “Pinteu Pintura” (1980-1990), a cycle that someone has described as the determining factor in the creation of the protean and most characteristic world of Antoni Miró. "Pinteu Pintura" images and worlds captivate the viewer. With striking contemporary icons (luxury car brands, drinks, cards ...), canvases that are part of the collective imaginary painting (Velázquez, Bosch, Titian, Mondrian, Goya, Picasso, Durer, Magritte, Toulouse-Lautrec, Dali, Joan Miró...) and mixtures or provocative collages, Antoni Miró forces us to look with different eyes as sacred masterpieces and makes us co-author in his eye and invites us to continue the path he has begun.

It is a pleasure with a point of restlessness to see the terracotta urn placed in the Louvre, where a happy Etruscan marriage lies in with a relaxed smile. Some are very similar in the Etruscan Museum of Volterra. They are enjoyable stories that have reached the end. What must have happened before? How was the life of this couple? Surely they wanted to be reminded of being together and happy. These are my concerns when looking at an urn. Who knows now what could have happened before and specially after in versions that make Antoni Miró of La rendición de Breda? In the original Velázquez, Justin of Nassau, leader of the heroic defence of Breda, delivers the key to the city to Ambrosio Spinola, general of the troops of Austria, and the occupant, with a gesture of chivalry, the reverence of the vanquished stops. The painter from Alcoi focuses in the play of spears, the rump of the horse of the winners and especially at the contact between victor and vanquished that he will recreate many times and in different formats, with various elements and motifs, metaphors and metonymic games to think about this and other political contexts. Although in Les Llances as did the Equip Crónica, Antoni Miró has also reinterpreted Las Meninas. Under the mastery of Antonio Miró, the family of Philip IV has a life never imagined by the characters. As in the original baroque, not them, but the real actors of kings who look happy or spectator, who feels hurt or challenged by a patchwork history of other battles, without much respect for the passing of time and historical facts.

Some friends, big men and myths

Throughout his career, Miró painted his family and many friends, like the missed Antonio Gades (Gades, La dansa, 2001) and Ovidi Montllor (Héctor-Ovidi, 2005, Proletariat 2006). But his illustrious gallery is dedicated to great artists and their characters: Picasso and Guernica (Gora Euskadi, Visca Picasso, 1985), Velazquez and the Count-Duke of Olivares (Retrat eqüestre, 1982-1984), the Mona Lisa (La Gioconda 1973, La famosa Gioconda, 2008), Dalí and melt the clock (Temps d’un poble, 1988-89) or the woman who looks through a window at the sea and the infinite sky with a Joan Miró (Mediterrània, 1988), among others.

Other portraits of Miró are the great men of our culture: Enric Valor, Joan Fuster, Joan Coromines, Antoni Gaudí, Pau Casals. They are in the distance headlights illuminate our personal voyages, the collective long journey. There are also two characters, crucial to understand the psyche and the polis, who could not miss in the iconography of Antoni Miró: Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx. And, of course, the most reproduced revolutionary myth enters youth 70 to 80: Ernesto Che Guevara (Che Guevara, 1970, Home lliure, 2001). And, alongside these big names, the anonymous who have emigrated, those who suffer oppression, begging, those that survive and struggle in Palestine, who from the difference claim the right to be considered equal.

See how they look at the art

During the 90s, Antoni Miró watched and put on the machines that built walls and destroy the coast, high pressure pipes, pipe piles, pilots of cigarettes and cartridges, a monster devouring environmental civilization and landscape. Given this, the painter escapes and poses an alternative. The bicycle has become the totem that creates an utopian world in a landscape diffuse of celestial blue tones. The Mediterranean cool eroticism of “Suite Erótica” (1994) anticipates the admiration for the Greek world. Already immersed in this new millennium, Antoni Miró will make his trip to Greece: the beauty of classical sculpture and architecture provided by the tourist crowds of art pilgrims from monument to monument. A good example of this stay in Greece, with stops at the Louvre to greet the Victoria de Samotracia, was exhibited at the Santa Barbara Castle in Alicante in the spring of 2008.

In recent years, Antoni Miró is set at the spectators and art spaces. Great works go to the background: La Gioconda in the Louvre watched by a crowd of curious and faithful viewers and fast photo shooting, scholars and art lovers who travel the shadow of the Parthenon or the Sun of Epidaurus, walkers of the Greek Museum with attitude, affection and respect for those who made that temple, or Kuro in Sounion. This trip to Greece with the pilgrimage is complemented by the great museums of Western culture, the British, the Metropolitan, the Guggenheim, the Louvre, Musée d’Orsay station, the Reina Sofia... Training itinerary in which containers, cathedrals of art, are now the object of his carefulness. As a former apprentice in a disciplined academy, Antoni Miró has now begun, with sixty years old, a trip through the Greek classics and the works of the great museums. He knows that the treasure that Ithaca promises is the journey itself and the learning involved in the route. I am sure that we will obtain new intellectual pleasures. Bon voyage, my friend Antoni!