The Water Tribunal in the work of Antoni Miró

Wences Rambla

Over the years, Antoni Miró has created a considerable collection of works, almost always in serial discourses. His series are large or small fragments of life, of the course of reality, be it political, social or historical. And all of this is focused not only of far-reaching questions – understanding universal issues – but they are also focused on others relating to the problems and tradition of the country that saw his birth. Or put another way, Miró is an artist of international renown whose work always implies a social objective while also promoting a series of ethical and aesthetic values that characterise the culture in capital letters of the Valencian Country. Not forgetting, of course, the fact that on many occasions he has given new meaning to images from the works of great universal artists, whether from the past or our own time.

With this series, Antoni Miró has devoted himself to a substantial work both for the breadth of the creative project and for its quality, which, of course, we have become accustomed to.

We now have in front of us a set of works undertaken in paint, digital graphics on canvas and lithographs, which are a testimony of great heritage value, be it quotidian or customary. It also alludes to what we understand today by a productive and sustainable economy. And this is in anticipation of what is involved in the effective management of water resources – the black gold of the 21st century – as brought together, symbolised and exercised by the Water Tribunal of the Plain of Valencia. A millennial institution dedicated to the administration of irrigation water, which ensures the observation of the rules appropriated for the best use of the shifts and batches in which it is distributed. Provisions that were originally part of the oral tradition and then written down, but no less effective when it comes to ensuring compliance.

And so, with his creations Miró makes visible for us, through his artistic journey, all those more or less ritualised moments and areas of L’Horta’s (the gardens of Valencia) geography where the specific actions promoted or ordered by the tribunal take place. He shows us the complex system of channels of Roman descent and Muslim implementation for the just and equitable sharing of the precious fluid from the river Turia.

In this sense, we can see the different facets and moments that are part of the Tribunal’s operations in its weekly meeting, attended by citizens, judges, complainants, defendants, etc. These facets and circumstances are reflected in the different scenes that our artist captures with great semiotic clarity: comprehensible and sharp and with formal perfection: a careful way of capturing the content made image through the prints and paintings that comprise this interesting and documented collection. Miró has invested much time in it and this allows us to appreciate with delight the precision of its drawing configuration, its reverberant chromatic attractiveness as well as the articulation of the various morphological elements that are used for their representation, in short, the whole set achieving a high degree of artistry.

Thus, we contemplate the scene of the trustees constituted as a sitting court and, in a previous image the empty seats they will soon occupy once they have put on their relevant clothes in the Casa Vestuari (Robing House). And all this under the stony, but no less vivid, gaze of the apostles, whose effigies dominate the tribunal from the top of the basilica portal, at whose feet the trustees’ and members’ deliberations and resolutions take place.

In another work we see them taking their seats which are laid out in a semicircle in the aforementioned Corralet (Enclosure) demarcated by a metal fence located in the cathedral portico. And in it we can see the sober elegance of the seats: leather and wood seats bearing on their backs the names of the eight mother channels to whose care the trustees are assigned: Quart, Benàger, Mislata-Xirivella, Favara and Rovella coming from the diversion dams of the left bank of the river Turia; and Tormos, Mestalla and Rascanya from those on the left bank.

In addition, the Water Tribunal of the Plain of Valencia, the oldest judicial institution in Europe, has its own Sheriff responsible for guarding El cercat (The Fence) or El corralet (The Enclosure). The members enter this when they have put on their black shirts to exercise their authority, and the enclosure will be surrounded by the public who comes to contemplate this unique audience with Gran expectació (Great Expectation).

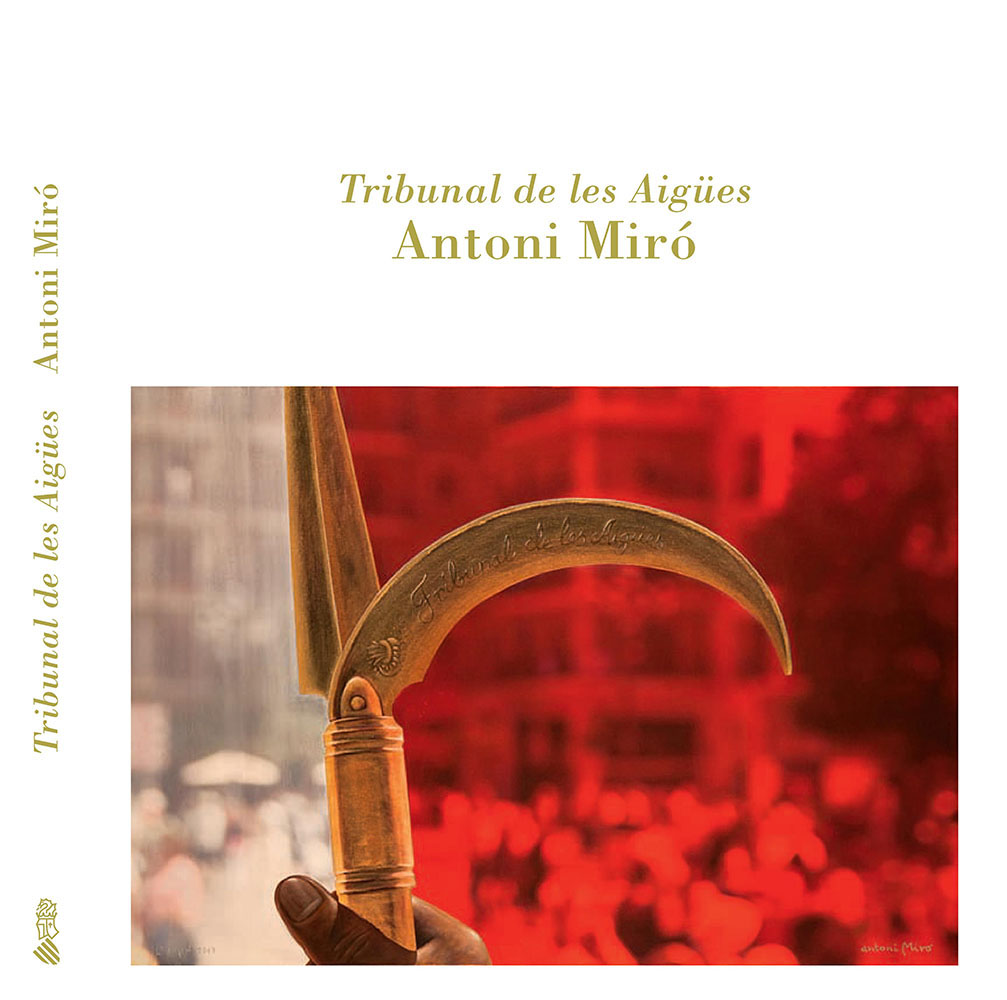

All this together with more details that appear and weave the string of scenes that Miró’s magnificent series shows us and which envelopes us in a mantle of emotions, of the processes of an event that is so ancient and essential so representative of this land, as well as so emotional for those who feel themselves to be Valencian. Thus, in one painting we see the Sheriff’s harpoon, the symbol and instrument used to open and close the paraetes (water distribution mechanisms) and floodgates, that is, to carry out the effective control of the irrigation: the distribution of the flow assigned to each user or farmer. In others we see the furniture – seats – being transferred by attentive attendants to form the aforementioned fence. Then, going beyond the surroundings of the Cathedral, other paintings show us the Repartiment or sharing of the water, the Partidor de Moros i Francs (Distributor of the Moors and Franks), Partidor de Quart-Benàger (Quart-Benàger distributor); the branching of the irrigation channels through which the water meanders towards weirs and diversion dams – Presa de Mislata (Mislata dam). We see the screw mechanism in Rovella-Túria which regulates, depending on the extent to which it is open or closed, the amount of water based on the corresponding distribution dictated by the Court. Miró also shows us in another acrylic the stone remains of the Arc romà de Manises (Roman arch of Manises), located in the distribution network, without forgetting that the water current moves the waterwheels in mills such as the Molí d’Aroqui (Aroqui Mill).

In short, and in conclusion, I would like to note that, implicitly or suggestively, we can imagine or deduce from these works the scrupulousness of the irrigation schedules, the obligations to keep the channels clean, if not an awareness of the importance that these or similar structures have and had in their economic contribution to the Valencian Country. Ideas, thoughts and suggestions that without a doubt can be glimpsed in this varied sample of images and views – in the guise of unique natural micro-environments – as the clear scenographic palimpsests with which Antoni Miró has so aptly elaborated this series.