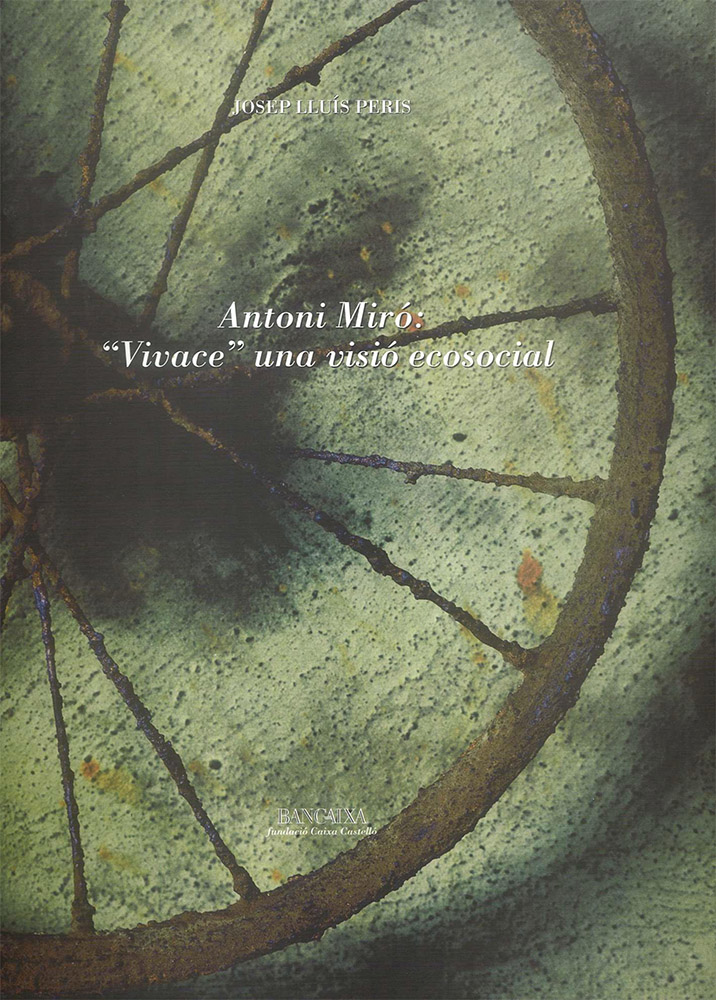

Antoni Miró: Vivace an eco-social vision

Josep Lluís Peris Gomez

Introduction

Regarding a conference on the prevalence of the avant-garde held at the Picasso museum in Barcelona three years ago to date, the Nobel prize-winning writer Octavio Paz emphasised the double front defining the aesthetic and artistic paths of modernity - rupture and restoration - stressing how the processes of restoration were not regarded as a return to the past or a m ere repetition, but rather as a recommencement. In this way he suggested we contemplate modernity as a tradition in the double sense of a break with forms inherited from the immediate past and at the same time, as a process of restoration —in other words, of the origin of new discourses which continue to present intrinsic bonds and renewed retrievals, recognitions that prom pt a new way of creating and influencing our surroundings, our collective conscience or its ethical/aesthetical dimension.

Rupture and restoration appearing as two moments of the same process, as manifestations of tradition which, on the one hand, evince the worship of history - socio-historical and artistic events regarded strictly from the viewpoint of their own historicity - while on the other, a tendency to mistrust history - a vindication of ahistoricity and a cult of novelty or an extreme concept of originality. The implications of rupture in the concept of change are such as those of restoration in that of repetition, and in this way, throughout the past few decades of the century now approaching its end, different aesthetic proposals have been formulated, giving rise to the variety and at times boldness of current artistic and plastic manifestations. The artistic discourses of the avant-garde and of all contemporary art have emerged from the realm lying between the representation of movement and of immobility, as from that of sensation and of logic. T he dimensions of metalinguistics and of interdisciplinarity, the reflection on the spheres of art itself and those of its signification, language and its ambiguities or equivocations, would also be some of the most relevant aspects to have been introduced, in an eclectic and disorderly fashion, in the new artistic discourses. It is in these discursive spheres precisely where Antoni Miró’s plastic oeuvre acquires significant importance, insofar as in his personal trajectory as a plastic artist he has accumulated an entire process of learning and of creativity, alongside the elaboration of a unique language which at this point in time is clearly distinguishable, while occupying a relevant position among those contemporary painters who have shown fidelity and coherence as regards their personal artistic intuition amidst the noisy confusion of modernity that sometimes seems to invade today’s artistic institutions, galleries or sub-galleries.

Starting from initially self-taught artistic parameters (as a true and tenacious autodidact), in his hometown of Alcoy, Antoni Miró began a prolific process of pictorial work. By means of a receptive intellectual activity, attentive to contemporary plastic trends, this process always evinced the need for attaining both a personal expression and the expression of the new challenges and paradigm s shaking society in the sixties. The progressive construction of a characteristic plastic language paralleled an experimental adaptation of the various constructive techniques and new stylistic resorts and, above all, a constant dynamic exercise of consciousness raising which enabled him to timely launch, alongside other plastic artists from Alcoy, an innovative programmatic proposal known as the Alcoiart group, in tune with the latest trends of the period. Such a representative leap forward strengthened his ran k as an experimental artist and constituted the beginning of an individual itinerary which has not ceased to make, during the past decades, important and noteworthy plastic and discursive contributions to both the Valencian pictorial scene, as to that of Spain on a national scale, surpassing as is well known, many of the frontiers that restricted the savoir faire of artists resigned to a basically and almost exclusively national resonance.

“Antoni Miró has already executed, and executed well, an extensive, complex and tumultuously vigorous oeuvre...”, was the way in which the essayist and thinker Joan Fuster summarised, in the early seventies, the painter’s artistic, and of course vital, trajectory. From that moment on, Antoni Miró would present us with the plastic results of an entire process of personal discoveries, reflections and experimentation with new techniques and styles. The series entitled Realitats (Realities), L ’Home (Man), L’Amèrica Negra (Black America), L’Home Avui (Man Today) and El Dòlar (The Dollar) constituted a very fertile creative period in which the artist introduced and reformulated the plastic trends of the avant-garde, and of the re-reading of these made by many of his contemporaries. The influence of American Pop Art or Op Art, together with that of Social Realism and the language of advertising and the mass media, could be clearly suspected in his works, despite being influences tinged and re-elaborated by aesthetical and discursive filters that the painter instilled into his plastic proposals. In this way he would attain a difficult equilibrium and coherence between these referential movements and the new fields of reference emerging from the glance and hand of the Valencian painter with both eloquence and a capacity of iconical impact on the immediate or apparently distant sociohistorical milieu.

In the decade of the eighties, Antoni Miró began an evocative process of restoration or retrieval of emblematic images from the history of art. Following the pseudo-revolutionary years of the sixties and seventies, the painter set forth on a kind of exercise of deconstruction/reconstruction of meanings related to the most profound paintings or prints of our pictorial tradition. This would be the decade of his great series Pinteu Pintura (Paint Paint), in which the artist introduced an ironic glance, at times in a heartless way, at others almost irreverently. Such a satirical glance, diminishing the importance of myths, is combined by the artist with a range of heterogeneous plastic proposals in which the material support of the picture, the com position and representations of recognisable and recognising images are fused into a humorous playful game of undeniable plastic and communicative quality. The persuasive function, the complicity with the spectator and the introduction of linguistic and metalinguistic elements acquire a pictorial value that strengthens the cathartic intention of the messages on the subject, thus impressing the whole series with a visual an d discursive coherence which is basic in order to achieve a disquieting suggestive impact that by no means allows the beholder of these works to remain indifferent or neutral. Rupture and recovery are combined in a difficult discursive and constructive equilibrium that furnishes the whole of this oeuvre with singularity and ‘modernity’, and above all offers a powerful persuasive complicity, both intelligent and sensitive, between com positions and spectator.

Vivace or paradox in eco-matter

The process of introducing multiple disciplines has been continual throughout Antoni Miró’s artistic trajectory, and recognisable in all his creative works. His oeuvre has been, and still is, characterised by persistent experimentation with the use of pictorial and expressive techniques, both as regards the support chosen for his painting and its constructive elements, and above all the introduction of vital values in which the painter adds communicatory dimensions taken from other extra-pictorial disciplines, such as the intentional and explicit presence in the picture of literary, media, advertising or, m ore recently, ecological facts.

Antoni Miró adds a personal group of vital values to his pictorial oeuvre, inserting in the significant (sensorial/form al) structure of each com position a universe of images that refer directly to the collective memory, historical, symbolical or programmatic experiences of the society which he is addressing, acquiring a communicatory function of undeniable persuasive and testimonial value. With a characteristic and very particular discursive skill, Miró introduces references from reality, stemming from various disciplinary spheres, into his plastic discourse by means of a representational, iconic and emblematic idiom and numerous expressive resources, as well as the language of matter or of residual objects incorporated into the plastic com positions. Any interpretative approach to his oeuvre implies a compulsory exercise of contextualisation/decontextualisation, as the fundamental keys in order to be able to read satisfactorily the enigmatic pathos o r the subtle irony that his work reflect are to be found in the implication and complicity of the extra-pictorial elements referring to the environmental culture and to the spectator. All this is possible if we become involved in a sort of playful and at times corrosive game in which what prevails is the complicity between work, spectator and awareness of the milieu in its eco-social and historical dimension.

These identifying traits of his creative work appear with an unchallengeable coherence in this Vivace series, where the author adds a personal discursive universe inhabited by images of reality that reveal a paradoxical vision of contemporary environmental and ecological problems.

Vivace: A Mirror or Kaleidoscope of Biodiversity

Communication as an immediate reference, as an expressive element or even as an iconic/linguistic self-referent, dominates much of Antoni Miró’s pictorial discourse throughout his trajectory as a plastic artist, and it is precisely in the present Vivace series where the communicative component assumes a practically structural dimension that notoriously conditions the com positional and expressive procedures of each of the works forming the series.

Without departing from the styles characterising his trajectory, in his new creations Antoni Miró introduces a consciously ecological and profound glance at reality. This new visual universe is ruled by the persistent presence of diversity, a diversity that acquires a new discursive significative dimension insofar as the author fully assumes the semantic and conceptual senses of the term biodiversity, which he adds to the paradigmatic universe of images.

By means of his particular language, Antoni Miró reformulates a certain way of regarding his surroundings, thus assimilating and complying with the new interrelations operating within the medium and the objects that inhabit it; such visual reformulating is posed by means of mimetic and deformative procedures, as well as by metonymic alteration of the designation o r the direct introduction of objects and artefacts in the parameters of an exclusively pictorial appearance.

An irregular and multiple landscape defining biodiversity gradually forms the continuum that covers each work or each visual sequence, dominated by a suggestive, playful and unpredictable glance at the world of objects. The author characterises this plastic experience of biodiversity using concrete singular elements, individualities that cling to a changing medium, only apparently still and timeless. Individual objects with a character and personality all their own that present themselves before the spectator on the same level or hierarch y of meaning.

This objectival and bio-diverse referentiality appears in each individual form thanks to its own material nature and singular characteristic traits. In this universe, repetition and anaphora are non-existent, despite the fact that objects, figures and landscapes seem to rep eat themselves. Each objectival entity, artefact or living organism lives its own life and history in a given reality or medium, and it does so in a unique condition. Thus a bicycle, each bicycle/artefact of each work, each wild beast depicted, each hum an figure, each of the machines assailing the environment, etc., harmonise, from their own singularity, with a similar universe where everything is interrelated and each element is merely a particular part of a whole.

In Vivace the painter adds a new discursive element to the universe of images of reality he has been progressively interiorising and transforming through his artistic work. This new referential sphere becomes concrete in the omnipresence of paradoxical interrelations established between contemporary man - determined by consumer society, the myth of progress and the development of technology - and the environment, nature and the alteration of traditional ecosystems due to these relations. This set of interactions between signs is at least susceptible of being queried and reformulated from new eco-scientific and eco-social approaches, as the author himself has pointed out in m any of his iconic and linguistic proposals.

These are the new parameters of reality in which Antoni Miró has decided to intervene and operate as a plastic artist and as a critical communicator. The artist’s involvement in this area of eco-social problem s is evinced by means of various thematic viewpoints and different constructive techniques with which he elaborates this personal visual edifice - the Vivace series.

These discursive aspects introduce the wide scope of themes and of real referents from which the painter extracts the pictorial and objectival matter with which he creates his works and com positions. In this way, the painter attention ranges from the fascination with industrial objects, artefacts and residue, to machines like power shovels, that rummage the environment. Miró’s critical glance is also attentive to certain antagonistic thematic groups such as the planet’s wild fauna, contemplated from a stance of fragility and the need for testimonials in the face of a natural world which is silently disappearing. It is also important to note the intentional introduction of a sort of sensuality and eroticism in m any of the images inhabiting his compositions. In these works eroticism becomes the principal axis of signification (for instance, Nua de gairó amb blau [Oblique Nude with Blue], of 1992, acrylic on board, 136 x 98 cm, or Poema d’amor [Love Poem] of 1992, acrylic on board, 98 x 68 cm), although in others it appears as an explicit element that remains latent in the hedonistic and sensuous treatment of certain figures and objects (Mountain Ball, acrylic on board, 68 x 98 cm, for instance). The inclusion of eroticism and sensuality in the Vivace series clearly responds to the reflective dimension the painter affords his plastic discourse, governed by ecological and environmental worries. The end product is the testimony of a world we are losing, a world that is vanishing yet which is reflected by the melancholia and sensuality of anonymous beings — women who keep the nature of desire and of eroticism alive. The presence of these nude bodies, ruled by a natural grace and by the beauty afforded by erotic gestures, is in marked contrast with the multiple presences of nature threatened by the cruel dehumanising intervention towards which we are heading thanks to the cold logic of machines and technology.

The sensuality of nude bodies, the innocence of wild beasts, of animals in a natural state, as well as the dignifying of hum an eroticism lacking morality, allow the artist to contrast an d to vindicate a set of values threatened by the new pragmatic and totalitarian mentalities on which the present models of progress and indiscriminate dominion over nature are based. In Antoni Miró’s representations, fierce animals and exuberant women that flaunt their sensuous qualities are symbolic exponents or metaphors of a lost world, replaced by another where the imperative of technological praxis and intelligence mark the new social and aesthetic values.

Procedural Elements and Constructive Techniques

The technique of acrylic on canvas or board, and the pure refined treatment of colour in order to identify objects and shapes are some of the pictorial supports with which the artist chooses to elaborate his plastic compositions, while the selection of large formats intercalated by others of medium-size enable him to build a personal expressive universe endowed with aesthetic unity and communicative coherence. In most of the works, drawing is the point of departure of the artist’s plastic creation; lines and profiles clearly adopt leading roles, while the flat tones assume an undeniable pictorial relevance. This colour and line complement one another in a balanced way, producing suggestive and surprising atmospheres.

Photomontage also occupies an important position in Miró’s creative activity. Developed in many of his previous series, this constructive activity is also present in Vivace, for instance in the work entitled L’infinit enyor (The Infinite Yearning) of 1993, or in Nua en la cendra (Female Nude in Ash), of the same year, works in which the collage technique, the superimposition of photographic images and contrast define, grosso modo, the personal application of this resort. With the use of this representation al technique, the artist penetrates into the communicatory and interdisciplinary aspects of plastic language. The appropriation of images stemming from the fields of journalism and advertising allow him to alter the signifying structure of the compositions, in order to invert the original meanings afforded by the contextual and signified relationships of the medium where such images arose. Antoni Miró adds a new meaning insofar as he deliberately arranges these images, awarding priority to their significative and communicative functions according to another hierarchical model he himself has established. This new connotative dimension instils these images and their messages with a persuasive capacity, evincing their original communicatory intention. The ironic and corrosive gaze of the new messages pervades the sense of these new representations, in which consumer society, the lie of the values transmitted by advertising’s ideal images or the accomplished frivolousness of slogans are mercilessly dissected by the author’s acute critical gaze.

To the discursive dimensions favouring communicative aspects and the critical and accusatory stance, we should add a third procedural element with which Antoni Miró introduces an ironic distancing in the totality of his plastic work, and which simultaneously characterises his personal style while referring to other languages and disciplines from within the pictorial planes themselves. This third element, present in many pictorial compositions, also operates decisively in Antoni Miró’s plastic language, and is defined in the inclusion of verbal referents inside the picture’s pictorial parameters. These verbal referents tend to assume a designating function that favours ambiguity and paradox by means of a linguistic game between significant and signified, thanks to which the artist prompts possible interpretations or apparently antagonistic significations. With these witty verbal resorts, Miró is able to alter some of the communicative levels implicit in all pictorial and plastic language, while assuming certain of the functions of the receiver. Thus the complicity between the artist and the spectator/receiver of the messages arises, insofar as the artist furnishes extra-pictorial elements that aid the process of de-codification and interpretation of signs. The piece entitled Parc natural (Natural Park) is one such example, where the picture’s very title supplies the interpretation of the message of the communicatory act the plastic work has become. Its title designates exactly the opposite of its pictorial and objectival representation, inside which we find words -partially hidden among remains and residues- with a clear de-codifying purpose and a vocation of provoking reflections and critical, ironic and even poetic comments. This natural park or reserve of a fragment of nature evokes a world in which the natural tends to be the exception, a world ruled by ecological malfunctions and environmental problems. Irony and sarcasm commit the spectator, obliging him to become aware of this reality: a book and a human skull amidst inorganic no biodegradable remains synthesise the critical pessimistic gaze of Antoni Miró, the transmitter of this message. In the hook one reads “Manual del plàstic” (Guide to Plastic), redounding even more to the fatality with which this park or landscape of urban residue is visualised. We may also point out the verbal reference appearing on a label of a parcel of rubbish that reads “Saint Pasqual rubbish dump”, in reference to a natural park on the Carrascar slope, next to the Font Roja natural park located between Ibi and Alcoyi. In this way the artist pronounces himself ironically on a real assault against the environment in one specific site of our geography.

“Vivace” or the Interrelation between Man and Nature

Everything produced by the power of the universe is produced in the form of a circle. The sky is circular, and I hear that the earth is as round as a ball, and also that stars are round. Wind, at maxim um force, eddies. Birds make their nests in the form of circles, their religion being the same as ours. The sun rises and sets in circle, like the moon, and both are round. Even the seasons form an immense circle in their mutations, forever returning to where they were. The life o f man is a circle, from childhood to childhood, and the same occurs in all things containing power. Our tents are round like birds’ nests, and were always arranged in a circle, the glade of the nation, nest of many nests, in which the Great Spirit wished us to rock our children to sleep.

(Black Moose, from the Oglala Sioux)

The precise words of the Sioux Indian Black Moose express and communicate a paradigmatic way of regarding and feeling reality. Despite the simplicity of the expression, we discover a powerful intelligence that evinces the balanced continuity of the age-old cultural tradition of the Sioux people.

Tradition and intelligence that reflect a primitive form of perception and of relationship with the environment, yet which continue to communicate with great eloquence an absolutely contemporary discourse or world view as regards profound significance and obvious poetic beauty.

Black Moose’s words acquire an aesthetic and poetic value of undeniable communicative quality as they masterly designate the deepest meaning of the relations that explain the ultimate nature of movement in reality. These dynamics are defined in the expression of the balance of the various elements, objects and beings in habiting their own reality.

Finally, what is the unique matter of this kind of primitive intelligence conditioning the gaze and the perception of the Sioux Indian? Without attempting to answer this kind of anthropological and philosophical question, I would at least like to take this perceptive and aesthetic dimension as a point of departure of a certain way of regarding the environment present, in a fragmentary and subtle fashion, in the series of works by Antoni Miró we are currently analysing — Vivace. By means of deliberately reflective visual representations, this series leads us to a special way of experiencing nature. Enigma and mimetic distance prevail in this way of experiencing the medium, while the author attempts to commit both the gaze and attitude of the spectator. In the images of nature and of the hum an objects or artefacts inhabiting it, Antoni Miró recreates a paradox that appears in the equivocal relationships explaining the state of abandonment of the natural environment. The painter’s glance at natural reality seems to tend to rediscover the primeval nature of the components operating in a balanced harmonious way on this reality. And with this discursive exercise using contrasted images, Antoni Miró claims and modernises a primitive way of regarding and understanding nature. The author takes up a vision of the world not polluted by the accumulation of prejudices and ambiguities surrounding the relationship between man and medium, and in this way he draws near a more innocent elementary vision of the universe. The place occupied by elements and man stems from a holistic supra-rational logic deriving from an ancient wisdom based on the harmonious cooperation of all the components of reality or of nature.

Nature appears defenceless and underrated by the arrogance as well as by the prepotence of the artefacts created by man’s technological reason. Such objects assume a monstrous aspect, inverting before the spectator their logical mechanical function that transforms the medium; in this way, a power shovel, a heap of industrial residues or a rubbish container are treated by the painter’s hand as truly emblematic exponents of contemporary man’s devastating anti-natural intervention in the environment. Let us consider, for instance, works such as Costa Blanca, of 1993, acrylic on canvas, 200 x 200 cm s., or Procés de camuflatge (Camouflage Process), of the same year, technique and dimensions. In this last piece we are able to observe how Antoni Miró creates a deliberate contrast between three elements that characterise three paradigmatic ways of creating objects: in the first place, the diffuse trunk of a centenary tree symbolising creation on nature’s behalf of a work of art in which human intelligence plays no part; in second place, the architectural creation, by means of stone as a natural element, of a fragment of a Neo-classical building as a symbol of hum an creativity through the harmonious balanced intervention of m an; in third place, the industrial design of a rubbish container elaborated from the natural element of iron subject to technological transformation as a symbol of the disproportionate creation of objects, thanks to which the natural environment of these elements is degraded.

In other works, Antoni Miró introduces a bicycle in the foreground of the picture, represented through multiple distorted or twisted versions of its constitutive elements as an object. Miró anthropomorphises the bicycle’s components by changing their usual meaning and altering the logical functions that characterise it. The communicative purpose and the playful, even ironic or signal nature is obvious, as is the deliberate designating presence of these artefacts in the naturalistic universe of the landscape com positions forming the background of each work. Let us consider, for instance, these com positional and discursive resources in works such as Bici-bou-blau (Bike-Bull-Blue) of 1991, acrylic on board, 68 x 98 cms., Empordà i boira (Empordà and Mist) of 1992, acrylic on board, 98 x 68 cms., or Agressió amesurada (Restrained Aggression) of the same year, acrylic on board, 98 x 98 cms., in the collection of the Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM). In these works, the reality of the landscape is visualised by the painter as an inanimate nature, devoid of concrete referential traits and recreated in an apparent calm or absence of life. The natural medium is displaced by the artist’s glance to a second plane, on a visual background and anonymous level that provokes a disturbing sense of strangeness by means of which the landscape of hare trees or skeletons of trees awaits a mention and explanation as it still has no meaning of its own. Objects obtain their full designating and explicative sense in these pictures; these objects are the bicycles, bicycles that tower over the landscape in the background, bicycles that organise the spectator’s gaze and alter its logic, bicycles that appear fragmented by the limits of the composition of the picture in a foreground overrated by the painter’s communicative intention.

The passive stillness of the landscapes contrasts with the suggestive presence of the constant uniform movement of the wheels of bicycles that evince the circularity of the movement, the circularity of time and of human action in the reality of space. The unequivocal recognition of the bicycle by the spectator becomes paradoxical insofar as the usual components of these objects are substantially altered by the communicator or inventor the painter Antoni Miró has now become.

I here is a communicatory need in this set of provocative enigmatic proposals, these plastic works governed by the forceful presence of the objects/artefacts/bicycle. The author seems to be fascinated by the architecture of these objects which are absolutely commonplace yet which, from his deconstructionist gaze, appear as an icon or emblem of a paradigm that symbolises or sums up a different stance as regards the understanding of technological progress and man’s relations with the environment. Miró presents the nature of these artificial objects as creative referents, simultaneously established as subtle elements designating the existence of conceptual models of reality, arranged starting from balance and harmony versus the stridency or unrestricted speed of models identified with the idea of progress and untenable growth.

These objectival references, the bicycles, enable the artist to carry out a pictorial and intellectual exercise of de-codification. This de-codification or deconstruction is basically visual, although it also has to do with signs. In this way the structural totality of these artefacts is altered from the functional signifying inversion of their parts. Therefore with this way of operating, the painter becomes a true inventor, subtle and ingenious, of new mechanical artefacts in which the communicative function prevails, not devoid of reflective purpose and with a precisely calculated dose of irony. The structure of these bicycles seems to be transformed by the artist towards an almost organic treatment, by means of which this same structure becomes a true multifunctional and multi-denominative skeleton. With this bold treatment, Miró generates a peculiar authentic oneiric, magical or sarcastic complicity with the spectator, a complicity attained through the binomial representational recognition/conceptual paradox, and one that tends to create common spheres of reflective questioning of the environment.

The artist’s proposal of deconstruction of signs and of aesthetic/reflective creativity through this plastic work governed by artefacts offers us the possibility of regarding the multiple realities of the objects from a de-codifying and creative view point, and of assuming new principles of identity and of perceptive innocence towards our surroundings.

The element of fate introduced by the painter in the reconstruction of the objects is clear in many of the parts of the compositions, evincing the relative changing nature of their functions. Moreover, Antoni Miró introduces and assumes several of the plastic languages recognised by the spectator, stemming from the universal history of painting, as he had previously done in the series Pinteu Pintura. In this way works such as Bici-rellotge (Bike-Clock) of 1992, acrylic on board, the artist creates the bicycle/artefact from the plastic and discursive language of Dalinian Surrealism, carrying out an exercise of true iconic intertextuality that reminds us of the famous oeuvre of Salvador Dali. We also come across this expressive resort in the work Bici aèria (Aerial Bike) of 1996, acrylic on board, in which the artist parodies the constructive mechanism operating in those objects that bring to mind the artefacts created by Leonardo da Vinci in the Italian Cinquecento. Miró updates this mechanism in the bicycle as an object, awarding it a new expressive and communicative dimension which is perfectly assumable in this series’ plastic and reflective discourse. In the work Maleta Dadà (Dada Suitcase) of 1992, acrylic on hoard, the artist also introduces this referential nature that affects the diachronic dimension of his plastic reflections, as well as the ability of intervening in the reformulating of the bonds between art and nature by means of a de-codifying glance.

Towards a Poetical Transmutation of Objects

Antoni Miró has recently introduced the primeval component of matter in his oeuvre with the intention of emphasising the aesthetical reflective message implied by the multifunctional nature of objects. In this way he has commenced a series within Vivace, a series in which the bicycle as an artefact assumes a true entity that promotes a powerful visualisation of the referent. Miró suppresses the usual mediation between spectator and the pictorial representation of objects, inserting real bicycles in the canvas, reformulated from the matter of pigments, oxides and earth. The plastic result is a group of works in which the different textures and colours distinguish the presence and identity of what had until then been bicycles proceeding from rubbish and urban residues. It seems as though the painter has intended to create a very personal expressive language, in which pictorial and theoretical reflection on human relationships and the ability of creating objects from the natural environment acquire a new aesthetic dimension.

The radical nature with which Antoni Miró assumes an eco-social and eco-aesthetical gaze in his new production is manifest in the introduction of new artistic values that stem from the reformulating and revaluation of the compositional and expressive elements forming a hegemonic part of the new works. Up until now the elaboration of a personal discourse around the new paradigmatic realities surrounding us had been conceived from essentially pictorial languages, in which representation, emblems, line or draughtsmanship, colour and texture had prevailed as compositional and expressive vehicles, perfectly adapted to the author’s artistic and communicatory needs. In previous works, sensorial and formal values harmonised coherently with a set of vital values that impressed unity and formal consistency on the universe of images the painter selected from reality and from the collective imagination, in order to reformulate it plastically and discursively in each picture or composition. Now the painter extends his expressive requirements and enters a visual field in which the image finishes up being replaced by the object. Miró arrives at a sort of constructive synthesis in which the iconic/linguistic referents, usually depicted following the two-dimensional planimetric parameters of painting, become directly objectival and material referents. Fascinated by the possibilities of formal, linguistic and conceptual evocation of bicycles as objects/artefacts, Antoni Miró directs his deconstructive reformulating glance at the real matter of these objects, at the true nature of these artefacts routinely serving as hum an locomotion, yet which in the artist’s eyes serve no other purpose, they are merely there. After having represented pictorially such a unique iconic universe on the theme of artefacts/bicycles, the painter enters the new three-dimensional volumetric reality, the reality of remains or residues formed by those bicycles withdrawn from everyday use, those found in the rubbish, rotted, mutilated... And this is the field where the painter operates as a plastic transformer, where he adds a visual and conceptual component that provokes aesthetic reflection, introducing a poetical dimension and acting, in short, as a transmute of objects or as a visual poet.

The fact that objects may turn into sculptures, artistic compositions or visual poems does not depend as much on their form al nature or on the functionality they display in different environmental contexts, as on the way of looking and the aesthetic and conceptual stance of the observer. When Marcel Duchamp radically introduced the paradoxical and reflective presence of objects in the context of the galleries exhibiting works of art, he was merely ranking all visual manifestations resulting from a purpose and a creative poetical glance on the same hierarchical and significative level. To the aesthetical consideration of the work of art, the ready-mades add the discursive and sensorial conceptualisation of the intellectual process and the process of aesthetic fruition as a subject-object in itself, artistic and meaningful. Duchamp’s Fountain and Bicycle Wheel mark the beginning of future possibilities for the conceptual deconstruction of objects and phenomena, and in this way the aesthetic experience partakes of the complexity of the perceptive process, in which de-codification and the talent for communication and evocation are transformed into artistic matter. Joan Brossa’s visual poems also enjoy this conceptual dimension of the aesthetic experience, adding a visual reflective universe formally supported by the communicatory and signal spheres of the mass media and by the relativity or versatility of the written word.

The expressive concomitances and the influence exerted by poetry on the aesthetic, function of plastic language are obvious in this idiom, in which the object plays a basically reflective and evocative part. We are not only thinking of the metaphorical function of objects - which, moreover, is quite recurrent even in the realm of everyday linguistic semantics - but also of the talent for signification and evocation that objects are able to assume from the angles of de-contextualisation and re-contextualisation, just as oral and written language are able to assume all this through poetry. The poetic paradigms that appear in Antoni Miró’s pictorial oeuvre are defined by the implicit presence of a specific group of our poets who have strongly influenced this painter’s creative processes. Poets such as Ausiàs March, Salvador Espriu, Miquel Martí і Pol or Vicent Andrés Estellés have left a mark on the painter’s literary education and on his artistic undertaking, as proved by a number of compositions in which the nuclear axis of the iconical representations and of the pictorial atmospheres are directly inspired by the worlds evoked by the poets, or by their very own images.

Object and poetry are therefore the formal elements the painter combines in his new material structures, showing a subtle visual talent for developing a new plastic language which we cannot define as ‘sculptural’ as the parameters in which he places and integrates the compositions are precisely the tradition al supports of painting (canvas or board). It is from this pictorial surface from where the series of bicycles, transformed by matter, pigment, oxide, earth and colour, emerge as objects/artefacts, in order to become plastic representations in which each object acquires an evocative reflective function thank s to its enigmatic suggestive presence. In the works Àngel blau (Blue Angel) of 1997, object-painting, 68 x 68 X 39 cms., and Àngel de fang (Clay Angel) of the same year, object/painting, 68 x 98 x 69 cms., the painter makes his plastic intention explicit in each title —these are paintings in which the object depicted acquires a completely pictorial treatment, while remaining as a metamorphosed or transmuted object. The visual and conceptual meaning should be traced in the picture ’s own dimension— in these instances, the colour blue and the dry clay are the signal elements that determine the objects’ meanings, not the objects’ apparent functionality inserted in the limited universe of the picture provided by the board. The matter formulating the object is of the same nature as the surface which it occupies; both form one and the same plastic reality, a unity composed of matter, object and surface with common significative and expressive dimensions. The significant dispenses with the former significant of bicycle in order to become a new significant with an entity of its own, which simultaneously opens an entire universe of new meanings determined by matter, colour and criteria regarding com position and visual organisation. In the work entitled Bici dinàmica (Dynamic Bike) of 1997, a painting-object measuring 80 x 160 x 24 cms., the artist delimits two visual levels in the com positional criteria that tend towards signal complementariness; the object partakes of the matter of earth and pigment from where it emerges, in such a way as the object belongs to matter or becomes the metaphor of a bare primeval nature — basic elements prior to human intervention. We may equally observe two fragments of the object, easily identifiable as wheels, detached from this material nature to show a different objectival meaning — the wheels have an explicit intention of being wheels, and make this manifest in their non-material but objectival appearance; they are wheels made with elaborate materials which can be used for the purpose for which they have been created, in other words, for moving, for simulating movement and executing it. The only requirement is hum an intervention, the driving impulse of a hum an action. Matter in a primeval state from w here the object stems, with which the object is elaborated and from where the man/object creator of other objects proceeds, meet, cooperate and complement one another. It becomes a powerful conceptual and metaphorical synthesis of the ethical and ecological dimension that explains the nature of matter, the nature of objects and of man. The bicycle adopts a function of synthetically signification that offers the spectator a sort of reflection on the identity and ultimate provenance of the objects invented by m an, and their relationship with the world of nature as of the contemporary societies inhabiting and degrading that same nature. The circularity of movement, the circularity of the wheel movement, the circularity of time and of natural processes, the evocation of circularity implied by primeval materials, the reflection on the provenance of objects in their etymological itinerary as words, society, culture, man... this is the poetic and reflective universe we are offered by the plastic and objectival construction that Antoni Miró has elaborated in his recent production in the Vivace series. Man, object, nature which when all is said and done are merely matter, and the matter they may become by means of a chancy, enigmatic and inexplicable process — sign, meaning, language.