Josep Albert Mestre Moltó

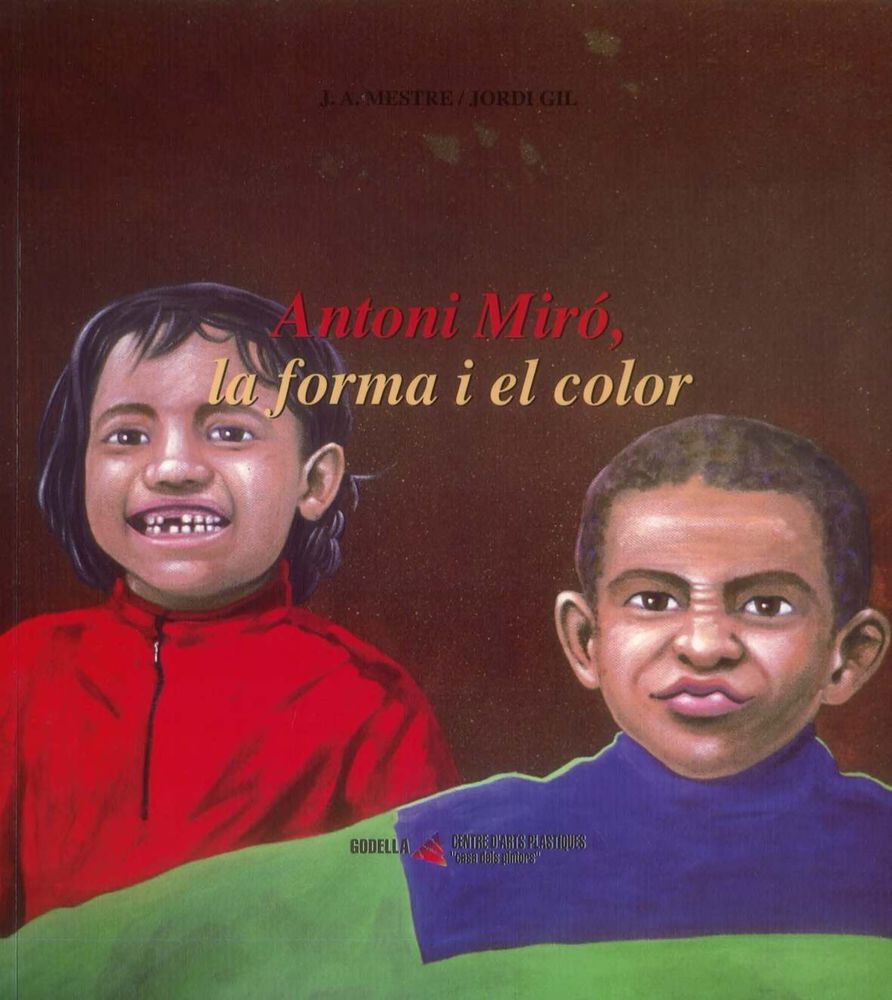

Salvador Espriu quotes poetically Antoni Miró in his work Homenatge al gran artista alcoià by saying: “no puc fer res per ajudar ningú / perquè jo sóc tan desvalgut com tu. / Però sense descans, amb viu clamor / em serviran la forma i el color”.

Notwithstanding the limits of the artistic action to transform society, as this poetic clamour suggests, it is true that the artist’s fundamentally pictorial career but also sculptural, mural and graphic path of the painter from Alcoy has distinguished himself, in a personal way, by an indefatigable and clamorous painting of denunciation and reflection on the contradictions of our society through, and about, the shape and colour.

Since almost the beginning of his pictorial career, he has followed a figurative expressionism and social realism in “Les Nues” (1964), “La Fam” (1966), going through “Els Bojos” (1967), “Experimentacions” and “Vietnam” (1968), “L’Home” (1970), “Amèrica Negra” (1972), “L’Home Avui” (1973), “El Dòlar” (1973-80), “Pinteu Pintura” (1980- 90), “Vivace” (1991-2002) until the current “Sèrie Sense Títol”. These two conceptual and formal elements -denunciation, shape and colour- interpenetrated in the structure of the own communication and expression media form an account among the representative and the plastic elements with the intention of closing a pre-established and imposed order by replacing it with an aesthetic and artistic reality within social realism in order to unmask, on the one hand, the ideologies underlying the societies of late capitalism or, in the Spanish case, the centralist and repressive nationalism; but, on the other hand, its media and communicative structure with the manipulative and alienating character that characterizes it.

In a non-affirming but critical sense, crying out for freedom and human solidarity means unmasking not only content but also languages. In this sense, Antoni Miró reminds us of Bertold Brecht’s reflections on the aesthetics of social realism: “Converting realism into a question of form, linking it to one, only one form and also old form means to sterilize it. Every formal element preventing us from reaching the root of social chance must be rejected; every formal aspect helping us get to the root of social chance must be accepted”1.

For this reason, he uses languages, techniques and several resources (assemblage, photography, cinematography, comics, and advertising posters) from the images of our developed societies and the linguistic techniques of the different “mass-media”, in a pop-art style of his careful figuration and the flat and inks tending to the monochrome. A combination and selection of an image leaving the viewer, in a clear desire to reinforce the communicative effectiveness, not in the passive assumption of a proclamation but, on the contrary, in an active and critical participation in the awareness of what is denounced from the valuable prominence of the aesthetic parameters.

For this purpose, it proposes an investment strategy of the communicative function of these images by giving priority to the linguistic resource of the decontextualization or separation of the image from its habitual context.

This resource influences the syntax, semantics and pragmatics of the work. In the first case, to the extent that the narrative plot is organized, the internal organization of its figurative systems. In the second and third cases, taking into account the symbolic, cultural and social dimension of the graphic and aesthetic references in which, in any case, the existing social contradiction in our contemporary reality is described. Simón Marchán Fiz claims that “decontextualization is not only a linguistic effect but a dialectical reflection of contemporary social reality contradictions on a local or international scale”2.

In the case of Antoni Miró, this contradiction, social and historical coincidence influencing its graphic symbolism is in relation to the oppression of the human being and of the peoples, especially of our Valencian people; with violence, racism, imperialism and ecological imbalance.

On the contrary, the decontextualization strategy is reinforced in communicative efficiency by a set of resources such as repetition, opposition, unusual superposition of images, parody and irony using, among others, quotes with emblematic works of the history of art (Velázquez, Goya, Titian) by giving them a new and different meaning, acutely critical, within the framework of a mainly ideological message organization.

Lastly, in the final series, the aforementioned “Sense Títol”, the painter delves into a kind of Chronicle of Reality by travelling into the interior of contemporary realities from his everyday perspective and dispossessed of any trap of, shall we say, official myths; from his personal honesty, subjective and critical to what he observes.

The trip is conceptually interpreted from fragments of a reality, in Antoni Miró’s opinion, full of social injustices and warlike conflicts, repression but also plenty of emblematic artists or politicians. Aesthetically and plastically, with a compositional organization and reinterpretation of the images coming from the “mass-media”, digitized and painted in acrylic on a rough texture focusing on and highlighting the space. On the other hand, the painter, subtly, emphasizes framings and pictorial signs and details which make him become particularly stirred or aesthetic citations for the ethical and aesthetic complicity of the spectator.

In short, in his latest work, we can continuously observe and talk about Antoni Miró’s desire of showing us the reality from an honestly critical awareness and a pictorial point to create effective communication spaces with deep reflection and aesthetic fruition.

1. Brecht, В; Estructuralismo y estética. Buenos Aires. Nueva Visión, 1969.

2. Marchán Fiz, Simón: Del arte objetual аl arte del concepto. Madrid, Akal, 1986.