Miró unleashed. On Antoni Miró’s erotic series

Martí Domínguez

There is a facet of Antoni Miró (Alcoi, 1944) that is not widely known: his penchant for eroticism. Some years ago, when I interviewed him for the book Estudis d’art, I was moved by one of the rooms of Sopalmo, his country house. Called the “sin room”, it was covered in erotic drawings, with titles like Amagatalls secrets (“Secret hiding places”), Fent camins (“Making ways”) or Gran meravella (“Great wonder”). Then, the painter admitted that he was shameless in that regard, and he said so casually, as if it had no importance. Eroticism has been present in the work of many artists. Some had no inhibitions, like Auguste Rodin or Egon Schiele; some were much subtler, such as Giorgione or Titian; others revisited the classics, like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Alexandre Cabanel, who with their concupiscent Venuses caused an outcry in the self-righteous Parisian society of the 20th century. We can also mention Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World, where for the first time in the history of art female genitals were painted as naturally and crudely as could be done in a painting.

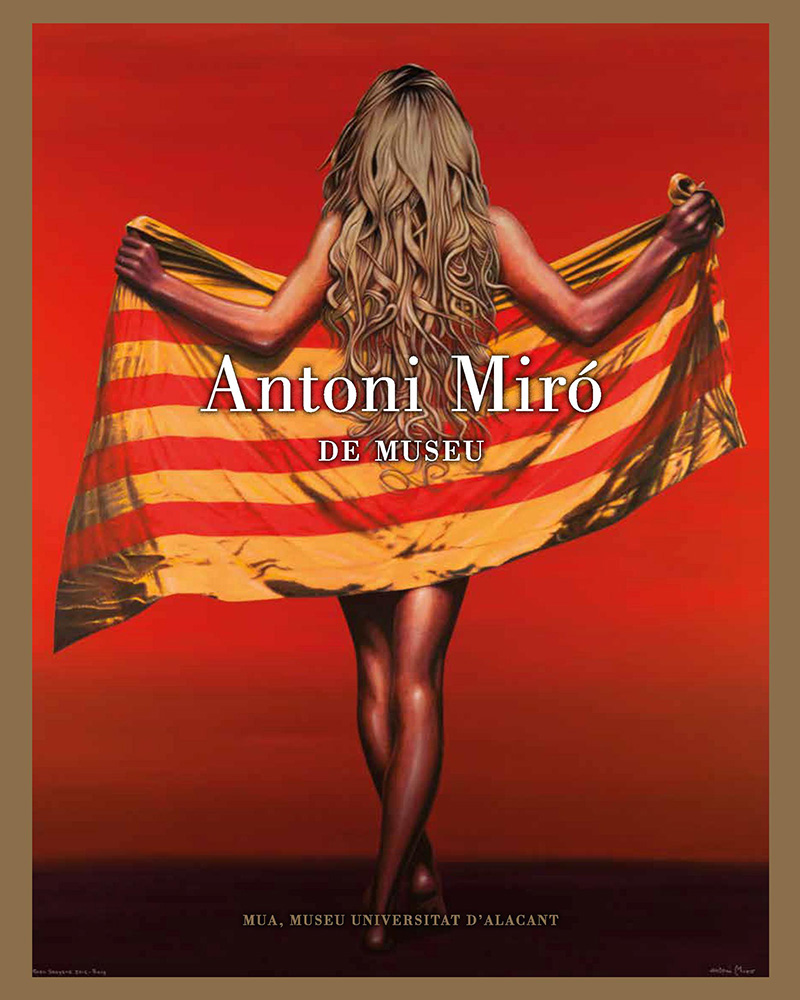

Antoni Miró is a lewd and disinhibited painter, brave in his brushstrokes, whose takes on the human body have become ever more uncompromising over the years. From the first drawings and etchings he made back in the 1960s to his latest series, released in 2018 and 2019, there is a process of disinhibition, as if the painter wished to convey the whole erotic potential of those female bodies. When he shows them, one by one, we experience a powerful feeling of desolation while looking at the living flesh, at the immense pictorial hammam. There is a voyeur in Miró, but also a scholar, someone wishing to indulge in that anatomy, which defeats him, never lets him go and is passionately loved by him. No doubt, this series is the work of an artist who takes delight in the female body, rejoicing at constrained femininity.

At this point, however, it is advisable to briefly discuss the contributions of these erotic series. One may say that Antoni Miró has painted almost everything, and that nothing exists that he is not interested in as a painter. He explores colour, geometry, perspective, portraits, and from there he moves on to sculpture, with his drawings on Corten steel. One of these sculptures is 25 d’abril, marking the defeat at the battle of Almansa and installed at the entrance to Gandía. It became famous because a conservative mayor had it taken to a spot where it was much less visible. His sculptures leave no one indifferent, especially his Sèrie grega. This series also caused outrage, as it included pieces (reproducing scenes depicted on Greek vases that had previously inspired a set of etchings titled Suite erótica) of an explicitly sexual nature, and some thought that the sexual intercourse was too evident in certain cases. His Afrodita, Jocs eròtics (representing a fellatio) or Joc antic are indicative of the artist’s cheerful character. And yet, all this is part of Miró’s cosmos, as direct and candid as if the painter, at over 70 years of age, had decided to speak clear, without beating around the bush, unafraid of showing things. With no boundaries. It’s Miró unleashed, particularly wild.

Therefore, in Antoni Miró we see an explicit desire to get rid of chains and restraints, to show things naturally. And his Nus i nues (2018-2019) series is compulsively disinhibited, overtly lewd, decidedly erotic, directly appealing to the viewer. Works like Mostrar-se, Platònic or Intuïció openly depict female genitals and strike us as crude, provocative, frank, Courbetian. But, at the same time, we are deeply captivated by the endless wealth of living flesh. Because what lies beneath is a heartfelt tribute to the female body. A profound and sincere tribute, unconditional and boundless, to human nature.