Suite Havana, Antoni Miró

Josep Lluís Antequera

International Association of Art Critics (AICA)

The winds of anti-establishment social criticism are almost always blowing over the seas Antoni Miró sails on his llaüt, with the lateen spread out and the conceptual elegance of his plastic irony on board.

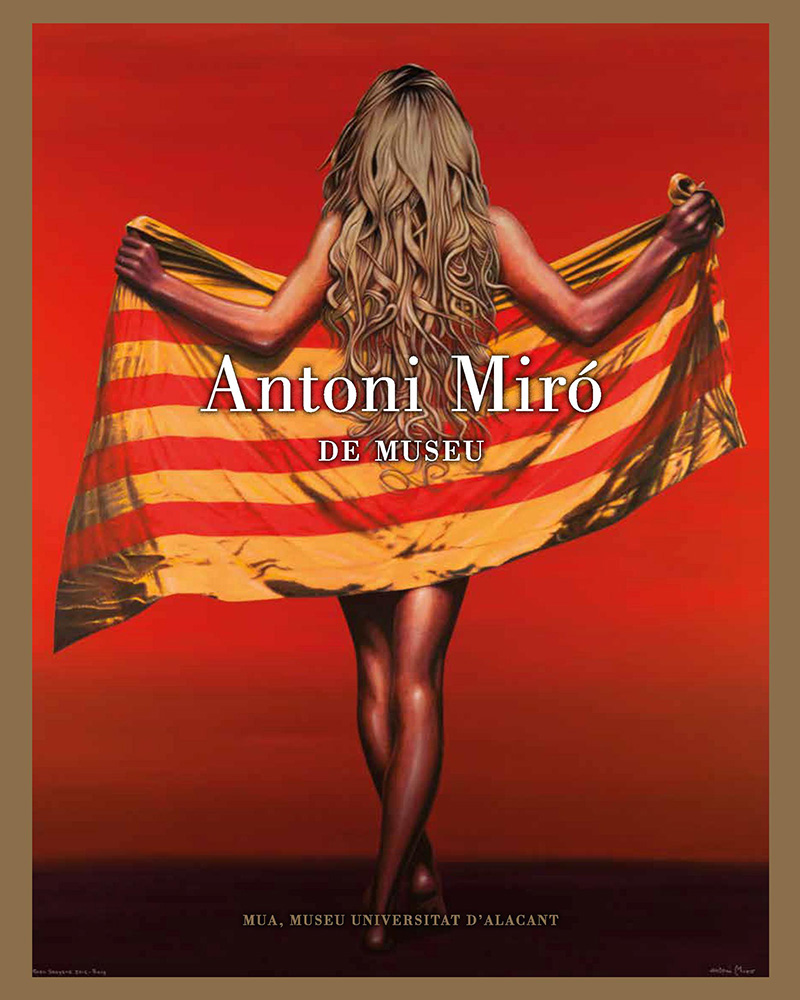

Miró usually awakens consciences by examining themes of social injustice, attacks on human rights, marginalisation, war, different forms of apartheid… He denounces the failures of society and takes a stance through commitment and solidarity. But when winds of change are blowing, he explores other topics with exquisite sensitivity, such as the features that build a country’s identity, age-old social traditions, the water tribunal, ecologism, architecture, portraits and more intimate human aspects, like sensuality and eroticism.

Eroticism in art has a long history. It all began with the monotheistic duo of Eve and her friend, the serpent, and continued with the lovers and the madness of Olympian gods and goddesses in Greek mythology, with its many nymphs, fauns and mermaids, the myth of Andromeda’s submission-domination, the sinuous copulation between Leda and the swan, the sensuality of Venus-Aphrodite, the curving forms in Rubens’ nudes, the Velázquez canon, Goya’s dexterity, Bouguereau’s and Cabanel’s odalisques, Cleopatra’s power of seduction and the symbolist moon-coloured flesh of Franz von Stuck and the Pre-Raphaelites, with the suggestive images of Ophelia and Salome. Examples include nudes by Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Ramón Casas, Renoir and Picasso, Van Dongen’s expressionism or Beltrán Masses’s decadent movement, the avant-garde, Paul Delvaux’s surrealist nudes and Balthus’s sensual advances, just to name a few.

But that which is good for art is not necessarily good for artists, who live in and experience the dysfunctions of consumer society. They are part of that whole, trapped in it, and end up exploring the various facets of that society.

When they look at the simultaneous images produced by the mass media, used in pop art in reference to consumer society, artists start taking stances through their plastic work, with different kinds of commitment.

One of these is the ethical commitment, based on the maxim “Nulla aesthetica sine ethica”. This is the guiding principle of those artists engaged in critical realism, founded on principles and values, striving to improve society. In their works, they shed light on contradictions, criticising their own society to make it change course; their tools are parody, irony, context and de-contextualisation. We see this in the socially committed work of Valencian pop artists Andrés Cillero, Equipo Crónica, Equipo Realidad, Antoni Coll, Sixto Marco, Joan Castejón or Manolo Boix, as well as Antoni Miró himself.

The second alternative is a radical pop art that goes one step further and directly confronts the values of the dominant society, in an effort to destroy it through the transgressive shocker pop movement, closely linked to American underground art.

The third option involves using pop art for documentary purposes, in purely formalist terms, just describing reality as it is, without questioning it, in a neutral chronicle that does not challenge or seek to change the status quo. Examples include Warhol’s or Lichtenstein’s pop art.

Jane Neal states that “the human body has the power to compel, to shock and to seduce.” Figurative artists are well aware of this, explicitly looking at the body and stripping it bare, emphasising the most erogenous zones as iconographic centres: buttocks, the pubic area, breasts, the look of desire… This is a plastic trend of great visual power, with flat inks that highlight the eroticism of the body. For instance, Tom Wesselmann, Richard Hamilton or Bernard Rancillac, in addition to Marlene Dumas’s objects of desire.

Antoni Miró’s “Suite Havana” sails these seas, but at different latitudes. Its basic principle is Ethos, the honesty of the artwork, sometimes evocative, sometimes providing a definition, with no semiotic ambiguity, but never enhancing or distorting anything. Antoni Miró uses Eros as a tool to express his inner pathos, putting aside (without forgetting) Thanatos and wondering if the petite mort we experience during orgasm is the avant-goût that leads to ecstasy or death.

Miró sails through foaming waves. Sometimes, he adds hints of eroticism; some other times, the crude nudity of the energy centres of the body, around the omphalos, is laid bare.

To create his “Suite Havana” nude series, Antoni Miró employs painting, collage and photography. In his collage works, he uses oxidised metal filings and varnish combined with painter’s tape, plastics or old newspapers he reuses, taken from other finished works, covered in random remains of pigments. All these elements transformed and relocated by the painter are placed at random to create shapes, thus originating images, outlines and new expressions where eroticism gives way to the expressionist recreation of matter.

When Miró explores the female universe in his acrylic works, his starting point is a photograph. With his camera, he captures all that draws his attention and chooses from among the thousands of photographs taken while travelling. Then, he uses diluted acrylic paint, which gradually achieves a methodical consistency as the artist defines the face and gives shape to the body; the woman, aware that she is being painted, photographed, observed, poses for the painter without shyness.

In this way, since the 1990s, the author’s retina has become imbued with the textures, landscapes and women of Havana, with the models he paints in various positions. Miró creates several works at the same time, in a process involving analysis and synthesis, from the generality of outlines or backgrounds to the specificity of positions, angles of perception, the feminine indulgence of the thighs, the eroticism of the lustful eyes, the naked buttocks that conceal their sex, their bodies suggestively shaped by vanishing lines, a look full of desire, the shapely legs that, like two sentinels, march down from the buttocks that protect their sex… Georges Bataille’s starting point, the pubic area as “a geometric incandescence […] perfectly fulgurating.” Like Paul Gauguin on Martinique, Antoni Miró is astonished at what he sees. His retina marvels at the sensuality of Havana, fascinated and moved by the authentic beauty of the Caribbean melting pot; and his experience, through his capacity for feeling wonder, is offered in the “Suite Havana” nude series.