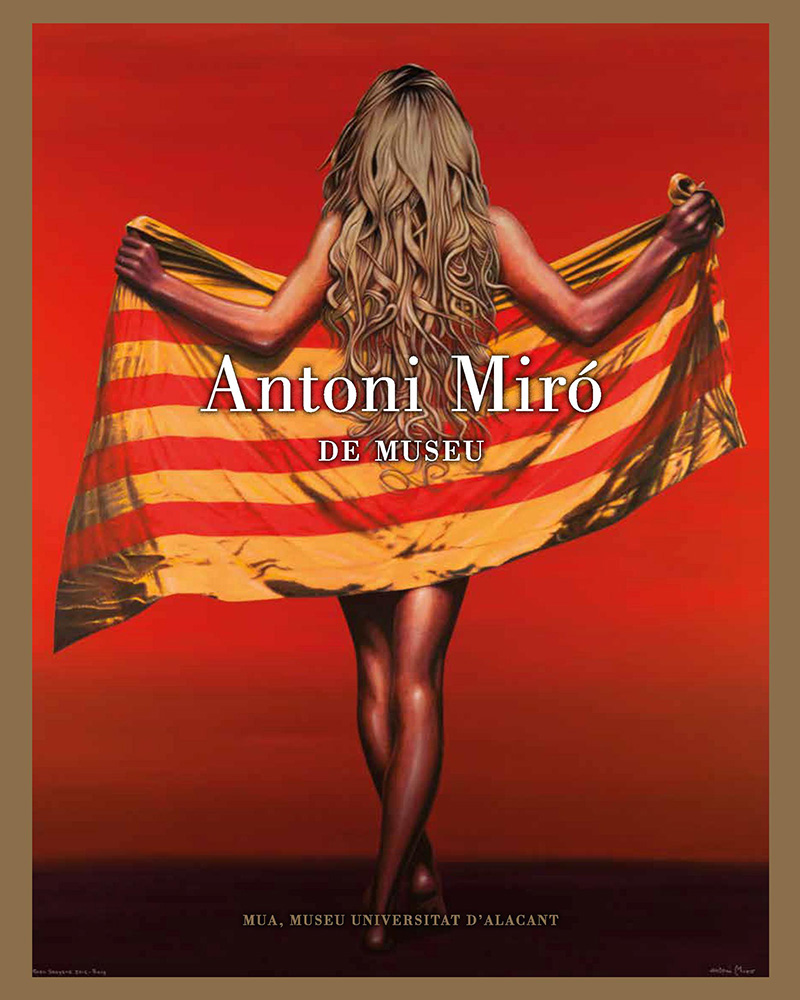

Antoni Miró’S Mani-festa series

Carme Jorques i Aracil

“Don’t stand there looking at these coming hours. Take to the street and participate. There’s nothing they can do against a united, joyful and combative people.” Vicent Andrés Estellés

Talking about Antoni Miró is talking about the identity and culture of, and love for, our Valencian Country. And we know he does it wilfully and at night, in such a way that, when the world wakes up, it has already been thought and done by Antoni.

His persistence and stubbornness, allowing no interference that may make him lose sight of his sustained and sincere commitment, with intelligence, honesty and irony, using his work to get us involved, are his hallmarks – there is no doubt about it.

With his great ability to draw inspiration from reality, he uses its codes through the media, which is the closest thing there is to skilfully, intelligently and effectively employing the weapons with which the media manipulates and attacks us. These weapons, like a boomerang, are used by Miró to denounce injustices and precariousness through his artwork, tirelessly, stubbornly, uncompromisingly, whenever he detects an injustice that must be condemned.

The images of everyday life that are produced en masse, the recorded facts, the injustices captured in snapshots taken in passing, they all go down in history and become elements for reflecting on it. These images, away from their objectifying and manipulative origin, are beautifully transformed into elements for reflection and denunciation. In Néstor Novell’s words, “an image is not just an act of denunciation – it is also a plea for tenderness, fondness, memory and subversion.”

In the Mani-Festa series, Antoni Miró shows the reaction of the people. It is a macro-polyptych of one people brimming with life, responding when attacked by the powers that be and the powerful; responding to their greed, to speculation, to a permanent and unsubtle attack; the permanence of power structures that keep us in a strange historical anomaly. As noted by Joan Llinares, “the dispossessed are the final verdict of the cause of money, a damaged asset of the unjust capital that is satiated with corpses, every day, every time.”

Antoni Miró doesn’t just pass by. He goes beyond the surface, tackles the social issue, takes sides and embraces the response of the people, filled with hope. He knows he is in the right; he knows it is fair, feeling like a winner, and the answer he gives is a sea of resolute and brave images.

With his work, he shows that the people have not been subdued: they can respond, and Antoni Miró joins them to multiply himself, thus creating an immense work – a striking, hopeful and joyful work that captures the spirit of Vicent Andrés Estellés’s words: “Don’t stand there looking at these coming hours. Take to the street and participate. There’s nothing they can do against a united, joyful and combative people.”

As rightly pointed out by Román de la Calle about the Mani-Festa series, “Freedom of Expression goes hand in hand with the right to protest. It is obvious that, in democratic societies and systems, protests are the best way to channel differences of opinion regarding the exercise of power. That’s why potential anomalies in the democratic health of societies are best detected when, by means of ad hoc norms and laws, attempts are made to stifle, reduce or minimise these instances of activism in everyday life.”

D. Betoret, in the media outlet El Punt Avui, writes as follows about Mani-Festa: “Antoni Miró reflects, through images and snapshots, the turbulent reality of a world in which streets, squares and avenues have been flooded with people protesting, in Antoni’s view, ‘not against a crisis, but against a great fraud.’ He puts the blame on politicians, bankers and financiers alike, who have ruined people’s lives: ‘If I could put them in prison, I would; as I can’t, I paint these things.’”

And Antoni Miró, through artistic creation, gives a passionate and intense account of repression, crackdowns and protests all over the world: the West Bank, Australia, Cyprus, Palestine, Portugal, Ukraine, the Valencian Spring, pro-independence rallies in Catalonia, protests against evictions… always looking attentively and giving an unequivocal and firm ideological answer.

Mani-Festa provides a picture of social revolt against power abuses, with which Antoni Miró puts “his action, both personal and creative, at the service of what he deems fair and, therefore, worthy of support, thus giving shape to the commitment involved in a work of art,” Josep Sou writes.

Antoni Miró’s work does not fit the mould of pro-establishment art – it is the product of active resistance, as was the work of those renowned artists who, in the 1950s and 1960s, were banned by the Francoist dictatorship. Instead of giving up, they resisted and chose to denounce atrocities and remain intellectually committed to respect for democracy and social progress. And Antoni Miró, like other artists who stayed true to their ideas, paid the price for his social engagement.

The Valencian Country was doubly repressed, as its history, language and culture were manipulated and systematically ignored. It was stigmatised as the Republic’s last stronghold, and its poets, artists, musicians, artisans, writers, scientists and many, so many people were regarded with contempt and unfairly overlooked. It was deliberately and spitefully dismembered, “from north to south, from the sea to the interior.”

It was not easy for those artists who never surrendered and chose to resist. Exiled artists spoke up to denounce repression and showed that Art is a powerful weapon.

Internal exile was terrible, but so was the harsh Transition period. From our mistreated Valencian Country, which received so many attacks from the extremely long dictatorship, few options were available: one was going north to survive “where they say people are cultured and free,” as pointed out by Salvador Espriu in his “Assaig de càntic en el temple”:

Oh, how tired I am of my cowardly, old, savage land, and I would so much like to go far away, further north, where they say people are clean and noble, cultured, wealthy, free, bright and happy!

Such was the case for our poets-singers Ovidi or Raimon, writers like Isabel-Clara Simó, Joan Fuster or Estellés, or artists such as Genovés. The second option was to create an impenetrable space where the artist could resist; this is what Antoni Miró did from the Mas Sopalmo country house, a true haven for culture and art, and an island of “active resistance”:

...and I love, besides, with a desperate pain, this poor, dirty, sad, ill-fated homeland of mine.

With this image Antoni Miró, sheltered behind the impenetrable walls of Sopalmo, shows a veritable fortress and think tank, preserving our language, art, literature and history (which are indeed ours) from the centralist narrow-mindedness that degraded them, always pressuring and trying to assimilate those incorruptible creators. Still, they could do nothing against Antoni, accompanied by the intelligent, wonderful and ever-supportive Sofía and Ausiàs.

Antoni Miró, so full of vitality, never ceases to surprise us, as a critical witness of today’s reality, which he “processes” with the strength and energy of those who do not allow themselves to be deceived, inviting us to think, to feel, to take sides. His work is a clear example of reflection in action. And this is exactly what he does; he is not a mere observer, but a participant, and anything he sees is included in his works.

His work helps us look, see and think, encouraging us to join this joyful and combative stream that carries the imagery of a whole nation.

Ever since he received his first award in 1960 and staged his first individual exhibition in 1965, he has produced an intense and vast body of work that has garnered international recognition. His work encompasses a wide range of techniques and artistic mediums, such as chalcographic engraving, planography, sculpture, painting, collage or infographics, with a complex and diverse plastic language used in numerous series and periods… And yet, while his work is of high significance, much more relevant is his tireless dedication to publicising and promoting artistic projects and our Art and Culture, which is proof of his love and generosity.

Isabel-Clara Simó, who knew him very well, said that “he paints to condemn reality, to look at it with blazing eyes, to break the silence of fatality. Antoni Miró is a fighter. And even so, he is very tender, full of love. You could call it solidarity, if you want…”

It is through Art that tenderness and sensitiveness become tools for construction and reflection, reminding us that we should encourage the values of peace, tolerance, justice, freedom and solidarity, to ensure that shameful episodes in our history are never repeated…

And Antoni Miró keeps walking, “so engrossed in thought, at night”, as his great friend Ovidi would say, tireless, silent and meditative… leaving a beautiful path behind him, brimming with sensitiveness, friendship, poetry and art, always with a touch of stubbornness and love for his country and his culture… our country, our culture.