The irrigation channels of Valencia and the Water Tribunal

VM Vidal i Vidal

The delta of the river Turia is formed by the territory that owes its topography to the special conditions relating to the delivery of the abundant waters of the river Turia when it flows into the sea.

It is possible to record both the flow and the force of its waters from the Roman era, through the description of Appian in his History of Rome. In it, Appian relies on the narrations of veterans and he places Sagunt between a mighty river and the Pyrenees. It is appropriate to mention that the translator of the text emphasises the defective accuracy of the oral sources since the river near Sagunt is the Turia, but historically the largest river is the Ebro.

This question should have stimulated the curiosity as to how a veteran should remember the adventurous passage of the Turia due to a cycle where the great volume of its basin delayed this passage or made it difficult due to the seasonal descent of the tumultuous waters that still cause floods in recent history, as in, for example, the flood of October 1957.

According to Cavanilles, in the dry seasons the flow of the river Turia supplied 128 rows of irrigation, and this translates into a flow of between half and one cubic metre per second of clear water and without increases in the irrigation networks that irrigate L’Horta de Valencia (the gardens of Valencia).

Given the topography of its delta, which gently slope from the north east to the south east, the territory provides land of high quality and soil variety from de Riba-roja, where the channels are fed by so many dams to irrigate L’Horta de Valencia.

The engraving by Tomás López Enguídanos for the observations on the natural history of the Kingdom of Valencia written by Antonio José Cavanilles, published by the Royal Press of Madrid in 1795, on page 195 entitled “Map of the particular contribution of Valencia”, clearly shows the eight irrigation channels that irrigate L’Horta and the 54 villages scattered across the plain.

The four channels on the left of the river irrigate 37 villages to the east of the city whose order downstream is:

- Moncada with a flow of 48 rows of water

- Tormos with a flow of 10 rows of water

- Mestalla with a flow of 14 rows of water

- Rascanya with a flow of 14 rows of water

The fields of the 17 villages on the right, looking downstream, are irrigated with channels flowing from south west to north west and their flow rates are:

- Manises with a flow of 14 rows of water

- Mislata with a flow of 10 rows of water

- Favara with a flow of 14 rows of water

- Rovella with a flow of 14 rows of water

The flow in a row is the water that passes through a section with a square span (2.25 decimetres)2 at a velocity of one rod per second (9 dm/s), which corresponds to a farmer walking. These figures equate to 2.252 × 9 = 45.5 dm3/s = 45 litres per second.

These figures and their precision provide information on the magnitude required to obtain a high yield on L’Horta de Valencia and its harvests. They are the result of a principle of cooperation that extends to the city as it consumes the produce and at the same time promotes greater production in L’Horta by providing the manure from its streets for use as fertilizer.

The mechanism is as follows: the pavement of the streets is composed of coarse sand and fine limestone pebbles from the river. With the continual passage of carriages with metal wheel rims the limestone is reduced to powder and, combined with the manure, it forms a material that is so useful in the fields that the farmers would collect it by sweeping the streets and removing hundreds of loads of sand and dust. This cargo extracted from the city streets was replenished with more sand and pebbles so that the improvement of the soil in L’Horta involved the gradual maintenance of the surface of the streets in Valencia.

An organisation was required to regulate and maintain the effectiveness and order of this elaborate system of cooperation, this institution is the Water Tribunal, whose jurisdiction still persists. The Tribunal is formed of eight trustees of the channels of L’Horta de Valencia, one for each channel. It is constituted as a tribunal at midday every Thursday, except for public holidays, under the arch of the cathedral door that opens onto the Plaça de la Mare de Déu.

There is no known documentary evidence from before the 13th century that refers to the Tribunal. In 1239, the 35th Charter issued by James I the Conqueror orders that the channels be governed “segons que antigament és e fo establit e acostumat en temps de sarrahïns” (according to what was once established and accustomed in the times of the Saracens). The appointment of the farmer trustees is by popular agreement, the irrigating land owners from each of the eight channels name their trustee at a time and in a way that is prescribed in their specific ordination. In addition to forming part of the tribunal, the trustee chairs the committee that manages the corresponding channel and presides over its affairs.

The judges, who don their robes in the Casa Vestuario (Robing House) on the Plaça de la Mare de Déu opposite the door to the cathedral, sit on wooden benches that have been previously placed in the Gothic doorway to this cathedral. The trials are held in the presence of an audience that is usually large as they are attracted by a true people’s tribunal made up of farmers and where the process used for the trial is totally different from those used in courtrooms, as the rhetoric is limited because the presentations, in Valencian, are regulated by the trustee for the channel at the centre of the dispute.

The Valencian Water Tribunal is held in high prestige due to the rapidity in resolving the water disputes that cannot afford any delay because this will affect the fate of the harvests. Therefore, its usefulness is recognised for the conservation of the agricultural interests of L’Horta based on the equitable distribution of water.

The tribunal’s most characteristic feature is the speed of its judgements and the economy of its functioning, as its judgements require immediate redress. The functioning of the tribunal relies on the oral tradition where nothing is written and where the interested parties themselves defend their rights without prosecutors or lawyers.

The procedure is as follows: the guardian for the channel in whose territory a dispute has occurred sets a date for the dispute to be heard at the tribunal. On the designated day the people summoned by the report by the guardian or other interested party appear before the tribunal. If the defendant fails to appear, they are summoned by a second sheriff. The trustee who is to make the charges admits the evidence of the witnesses or agrees to recognise an expert, if this is required.

The justifications presented to the tribunal are discussed by the trustees without the presence of the interested parties and it is decided by a vote according to the provisions of the regulations for the irrigation channel affected by the dispute. The trustee for this channel abstains from this vote to further guarantee the impartiality of the decision.

The ruling can be deferred to another hearing when there is a need to hear evidence and the interested parties are always informed of this and called back to appear at the tribunal. The judgment is final and is executed by the trustee who brought the case, it is undertaken without any further formality.

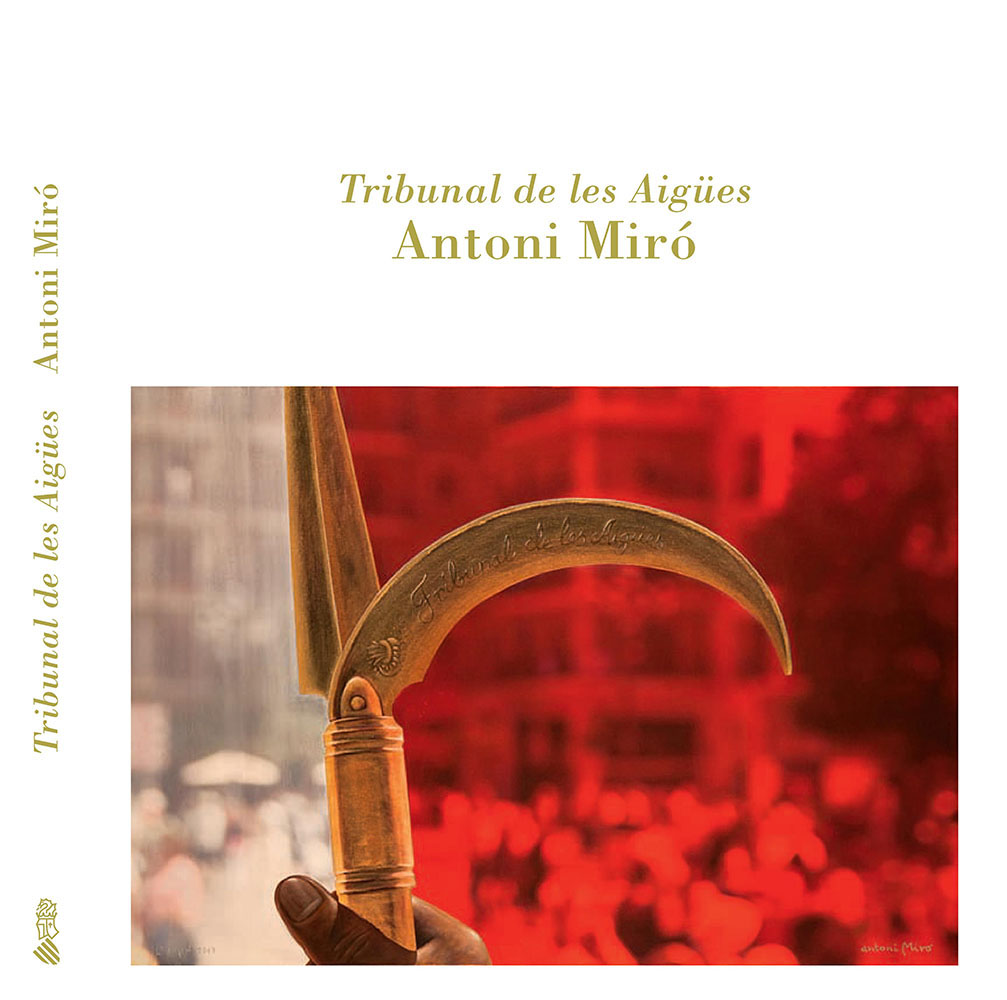

The pictorial material that we can see in the exhibition by Antoni Miró is also an unquestionable document of a state of the history of the Valencian Country that shows how the anonymous and silent witnesses that are the dams, irrigation channels, floodgates, siphons, etc., testify to the reality that still survives under the protection of its institutions.